It’s not often aid hits the front pages. There’s been a lot of commentary in the last few days about the future of Australian aid to Papua New Guinea and the implications for aid of the Kevin Rudd-Peter O’Neill agreement concerning boat arrivals. Let’s cut through the confusion to explain three things that aren’t going to happen — and three that will …

One thing we know is that we won’t be giving our aid as cash to the PNG government, despite Opposition Leader Tony Abbott’s suggestion to the contrary. We used to do that, but the practice stopped at the turn of the century, and there is no appetite on either side to go back again. In fact, there is no suggestion that there will be any change at all in the way projects are implemented.

Another thing we can confidently say is that there won’t be a shift in the sectoral priorities of the aid program. PNG PM O’Neill said as much on Wednesday by clarifying that his priorities (education, health, law and order, infrastructure) were already those of the aid program.

Third, we can be confident the Manus solution won’t itself be paid for by aid money. Offshore processing hasn’t been and can’t be counted as aid.

So what is going to happen?

First, there is going to be more capital spending. Look at the announcements made by Rudd in PNG and then in Brisbane with O’Neill on Friday. Three were restatements or expansions of long-standing initiatives and proposals: more Australian police, matching funding for the tertiary sector, and drugs for PNG clinics. But the other three were new capital projects: rebuilding the Moresby Court House, the Lae hospital and the Ramu-Madang highway.

This shift towards more capital spending is the biggest change we can expect in the aid program. There has been little Australian-aid-funded capital spending in recent times. Most Australian aid to PNG goes to paying for advisers or scholarships, or to support existing services, such as getting drugs to rural clinics and maintaining roads. PNG has long wanted Australia to focus more on capital projects (or “high-impact projects”, as they’re referred to). O’Neill has achieved this. This is what he means when he says he has achieved the “realignment” of aid, which previous PMs have failed to do.

While it is a significant change, it is not a huge one, at least not yet. We don’t have any costings, but the annual costs of these projects will likely be relatively small by comparison to the $500 million total of Australian aid given to PNG every year. The three capital projects are also at a very early stage of preparation. It might be a year or two before the detailed feasibility and design work is complete. There will also be contentious issues to negotiate. For example, Australia would not want to rehabilitate a hospital without discussions around maintenance and management.

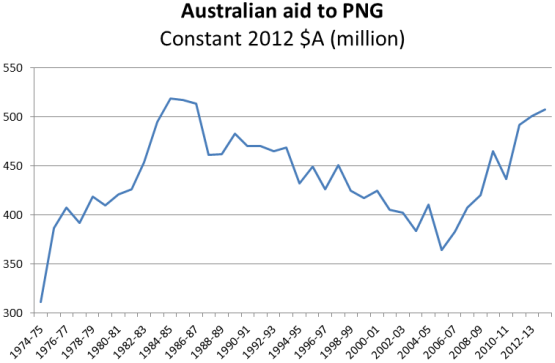

Another thing we can be confident about is that there will be more aid to PNG; it’s unlikely the new initiatives will be paid for by cutting back existing initiatives. Aid to PNG has been increasing since 2005, reversing a long earlier decline (see below). It was already scheduled to increase to about close to $700 million by 2015-16. Will aid increase by more than it would have without this agreement? You’d have to think it would, but it might not be by much.

Third, one would have to think that the leverage of the PNG government will go up in relation to the aid program in general and the Australian government’s leverage will go down. Aid projects frequently involve differences in perspectives, if not straight-out disagreements, between the donor and recipient governments. An empowered recipient government is important for aid effectiveness, so this change in leverage might not be a bad thing. However, it will weaken Australia’s voice in relation to important PNG policy issues.

Finally, there is also one major uncertainty. Manus can’t be charged to the aid program, but what about the cost of supporting refugees in PNG after they are processed? This could be counted as aid. Immigration Department guidelines say that resettling refugees in a developing country is an eligible aid expenditure. However, PNG doesn’t seem very keen to resettle a large number of refugees. How important a liability this will be remains to be seen.

Overall, then, what can one say? I finish with three points. First, more detail is needed.

Second, the adjustments to the aid program seem to be fairly minor at this stage. However, they could grow over time. One possibility is that what has been announced is just the beginning and that many more capital projects will be proposed and developed. Another possibility, noted above, is that large post-processing refugee support costs could be charged to the aid program.

And thirdly, we don’t know enough about the new initiatives to make a full judgment, but the shift to capital projects, even if just at the margin, is unfortunate. We all know that maintenance is underfunded in PNG and that maintenance has far higher returns than new construction. Why then would we shift the aid program from maintenance to construction? Australia’s commitment to supporting recurrent programs — not only maintenance, but drugs and text books — has been important both for keeping services going and important symbolically.

It is unfortunate that this commitment has been weakened. It is understandable that PNG should want to see more visible results from the Australian aid program, but Australia should keep its focus on maintenance and service delivery.

*Stephen Howes is director of the Australian National University’s Development Policy Centre and was an author of the 2010 independent review of Australian aid to PNG which reported to both governments. This article was first published at DevPolicyBlog.

STEPHEN HOWES: My answer to the asylum seekers issue is for our government to marginally outbid the people wanting to come to Oz. The people smugglers would get their money and, doubtless, we would be saving money presently being squandered on fruitless PR exercises.

Stephen, thank you for your clarification and reservations and your comment on progressive reversals of leverage between donor and recipient. I have seen in recent years in my old electorate of Morobe Province how rural roads have deteriorated through lack of maintenance and how rural medical services suffer by key items for treatment not being in their store room – for example glucose bags but no feeder needles to insert into patients.

I strongly support your view that Australian assistance continue its focus on maintence and delivery efficiences.

Having worked for both AusAID and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) I see a massive gap in donor coordination re development assistance to PNG. The “professionals” in funding bid capital projects are the World Bank (IBRD)and the ADB. Why can’t the Banks and AusAID get togther and design an “integrated” package of a blend of capital construction and building maintenance capability and service delivery efficiency? The result is likely to be a sustained development asset.

Idle thought from Tony Voutas. Beijing

VA – now THAT is lateral thinking! Take it a step further, buy all rotten,leaky,unsafe boats on the south coast of Java.

As foreign aid to start new enterprises, such as boat building it can’t be beaten.

AR: RE THE BOATS: Strip ’em and ship ’em from Asia to Australia and turn the timbers into lavatory paper/office paper/stationary/cardboard instead of using our native trees.

Of course our loggers and tree fallers will lose out but think of the profit of this new sort of revenue to the paper companies. We all know how badly our foreign owned mega-companies need more money.

You don’t think our recycled loggers, tree fallers and General Motors workers will find boat building a little too difficult? After all they are used to working for really big companies like General Motors who are subsidised-and who in turn blackmail our governments for the so-called benefit- by/to the taxpayer. Not forgetting the workers themselves being subsidised by the tax-payer, to work for the car industry and to turn out vehicles also-by way of extortionate prices-paid for by the taxpayer, whenever some poor dumb bästard needs a new set of wheels, might be too demanding? After all, they’d have to be able to read which plank belongs where.

Or did you mean the boats to be rebuilt in Asia?

Too difficult! I’ll leave the mechanics of the business to you!!??