Australia’s international trade position is continuing its steady march to a position where monthly surpluses are increasingly common.

The balance on international trade in goods and services is being driven to surplus by a surge in export receipts, which in turn is a key factor supporting bottom-line GDP growth. This in itself is welcome news at a time when the mining investment outlook is gloomy and as policymakers strive to maintain a 3% GDP growth pulse.

While export growth is strong, softer demand for capital equipment is dampening import growth which is further helping the move to a trade surplus.

In the last three years or so, Australia has recorded a monthly surplus for international trade on 25 occasions, including in each of the last four months. The ongoing lift in export volumes from the mining sector, in particular, and as the recent fall in the Australian dollar steadily boosts export competitiveness, more monthly surpluses will be assured.

While there is nothing automatically wrong with international trade deficits, especially when the import side of the ledger is concentrated on capital equipment, which is used to boost the productive capacity of the economy, running surpluses based on stronger exports (as opposed to a recessionary inspired import fall) is desirable. This is effectively where Australia’s external accounts are heading.

Australia’s export links with Asia in general and especially China remain on a massive growth trajectory.

In 2000, China took less than 5% of Australia’s exports of goods and services. Now China takes over 25% of all exports. This is why trends in China’s economy and its policy settings matter so much for investors, financial markets, corporations, the Australian government and the Reserve Bank.

But Japan remains Australia’s second-largest export market, accounting for around 18% of all exports, a level that has held more or less for over a decade. South Korea and India together account for a further 12% of Australia’s exports and are obviously important markets. In total, Asia takes around 75% of Australia’s exports, which is why our engagement in the region is so important.

It is no real surprise to see that the European Union accounts for just 8% of Australia’s exports, about half the level of a decade earlier. The US has never been a major export market for Australia and it is now less relevant than ever, taking just 5% of all exports — the same percentage as India.

In other words, Japan is now a larger export market for Australia than the EU and the US combined.

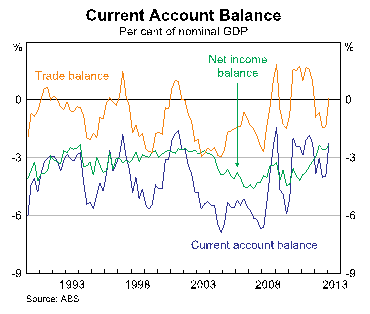

The move to an international trade surplus has helped diffuse the residual concerns, if there were any, about the current account deficit.

With surpluses on the trade balance, the current deficit is now accounted for by the net income balance (deficit usually). Net income, in this instance, is effectively made up of the outflow of dividends and interest to foreign holders of Australian stocks and bonds less the inflow to Australia from our holdings of foreign stocks and bonds.

With massive capital inflow into Australia over the past couple of centuries, there are now always more outflows than inflows, hence the deficit on the net income balance.

As the chart below shows, the net income balance has narrowed in the last few years, no doubt a function of the very low interest rate climate prevailing around the world. This narrowing in the net income deficit, together with the move to trade surplus, has caused the current account deficit to fall to below 3% of GDP. This is near historical lows and is well down on the average of around 6% of GDP in the period between 2001 to 2008, and it is getting close to it lowest level since the 1970s.

Australia’s economic transition from a mining investment boom to a more balanced growth mix has exports rising as a critical aspect of that trend. While the Reserve Bank and Treasury forecasts are both reliant on household consumption and dwelling construction to contribute to GDP growth over the next two years, stronger exports will no doubt figure in the plan to lift GDP growth above 3%.

On present indications, the move to an international trade surplus and rising export volumes, especially from the mining sector, suggests GDP growth is on track to hit 3% by year end and should hit 3.75% in 2014. It is not all that common for Australia to have an export-led growth phase, but it looks like one is forming about now.

*This article was first published at Business Spectator

Just how is the Howard Free Trade Agreement with the USA tracking as exports to there decline and decline. Very nicely for Australia, he said ironically.

Idiotic and politically motivated to kiss the backside of the odious Bush and costing us money ever since. The only good thing to come out of it was the line: Vaile [National Party Minister] can’t even sell sugar to Americans.

I would want to see a breakdown of the exports to these different markets to know if it is a good thing or not. I suspect that our exports to Asia are mostly primary resources such as raw ores, bulk grains, unprocessed fibres (wool, cotton) most of which we buy back in processed format (steel, aluminium, vehicles; clothing, wool quilts etc). There might be some minor component of perishable foods (including dairy) plus services like education, tourism (which is puny for our size and attractions) and maybe financial. Very little manufactured items or anything much with high value-added.

The reason for our declining exports to Europe & US is almost certainly a reflection of our pathetic inability to provide anything they need or want (combined with regulatory bans on imports to EU or strict miserly quotas such as beef & sugar in US). Instead of just rejoicing in our Asian trade “success” I believe we have to be deathly worried that in time it will follow that of the advanced nations.

Dogging contacts site for Australians looking for outdoor Dogging, swinging, personals or contacts and dating