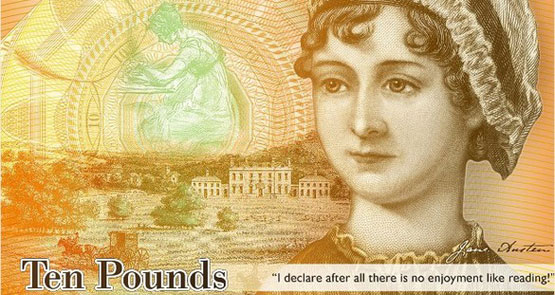

Twitter has said it will introduce a “report abuse” button, following a cycle of rape threats, beginning with those against an activist who had successfully campaigned for a woman — Jane Austen, as it turned out — would go on the new UK 10-pound banknote. When other prominent women, including a Tory MP and journalists, protested these vile attacks and criticised Twitter for not responding to initial complaints, they too received rape threats.

The libertarian response — that we should all just put up with this — was inadequate, since it didn’t recognise the hybrid public/private space that Twitter is. You wouldn’t tolerate such threats — even if they’re intended only as discomfiting abuse — at a public meeting, or a party. On the other hand, you wouldn’t want someone making such a remark to a friend in the street to be arrested.

Trouble is, Twitter is neither public walkway nor private party — but both. If you tweet something to your 150 followers, is it public? If you add a hashtag that puts it in a mass readership stream, is it private? If people retweet it, are you responsible for their publicising it? And so on.

That certainly suggests that the process of reporting abuse should be made easier, more straightforward, and more likely to lead to action. But is a button the right model for public speech? After all, what an “abuse” button most resembles is an emergency switch or a fire alarm — both devices designed as a response not to speech, but to an event, whose rhetorical character is nil.

An “abuse” button tends to elide the idea that an argument has to be made against the allegedly abusive speech act. Not a difficult argument to make in the case of “Dear X, I am going to rape you”, if X is an actual person, but what about a whole series of grey-area language? “Dear X, I am going to f-ck you up”? Visceral language, or abuse? Does that status change if it’s a man speaking to a man or a man speaking to a woman? And so on.

What about rape jokes, which have become what “new” racist jokes were a decade or so ago — a way for comedians to get a shock edge on competitors and a reaction out of jaded audiences? These have become the subject of a fairly major campaign about misogyny, though for years their most arch practitioners were comediennes like Joan Rivers and Sarah Silverman.

Should they be told? Probably not, but the whole point about stand-up is that it acts as a conduit for the social unconscious, a release valve for the repression we apply elsewhere. Thus, “new racism” came in at the same time as statutes on racial vilification and hate speech. As did the the new wave of vicious anti-homosexual jokes by people like Eddie Murphy.

Following that, such joking entered the everyday, with a covering of irony. First, “gay” became an acceptable synonym for “lame”, essentially repeating the idea of the “pansy” from the 1950s — the homosexual cowering in same-sex attraction from fear of the female. Bitch became a synonym for woman, even though it encoded an idea of subjection and ownership. Lately, the old sports commentator “plays like a girl” expression has become ubiquitous as an expression of a second-rate effort, or weakness — especially, it seems, in stuff intended for consumption by children, like superhero or animated stuff. As much of it seems to be written by women as by men, suggesting that the idea has become internalised, once again under the cloak of irony.

“… this stuff, with its cultural epicentre in the US, has arisen since 9/11 and then the Afghanistan/Iraq invasions, and the assertion of supremacy by a wounded West.”

In some ways this latter trope is the most insidious of all — the jokes are there because just about all we teach on the surface these days is equality and tolerance, and the Holocaust and etc, etc. Racial and sexual violence, as far as one can tell, is significantly down on what it was three or four decades ago — and because of that and its reduced acceptability, more reported, thus giving the appearance of an epidemic.

The social unconscious may be the manner by which this stuff comes to the surface, but that process doesn’t determine its content. After all, in more positive modes, a different content arises — the Victorian obsessions with the painted n-de, for example, simply erotica hiding in plain sight. This new return of the repressed comes about because our culture simultaneously affirms tolerance and equality — as the social super-ego or conscience — while expressing its identity through war and domination.

Thus this stuff, with its cultural epicentre in the US, has arisen since 9/11 and then the Afghanistan/Iraq invasions, and the assertion of supremacy by a wounded West. We essentially reprised the hypermasculine culture of the Greeks as they asserted themselves against the Persians as the inaugural event of Western civilisation, with the wars that produced philosophy their justification.

Rape, misogyny, hatred of homosexuality is a disdain for the penetrated, the occupied, grouped as one. The more fragile the sense of domination becomes, the more hysterically such disdain must be asserted. By that crazed internal logic, for such people, putting Jane Austen on a banknote absolutely demands reassertion of power by rape, all the more because she has unquestionably earned the right to be there.

Thus, the masculine body must be continuously, compulsively reasserted until every year 10 girl has a permanent sense of being second-rate at the same time as being told she can do “anything she wants!” (look at Jane Austen!). Such a culture, far more widespread than a few nasty rape remarks, has returned because an alternative idea of human power — a shared one, expressed vis difference — has yielded to identity, on the male model (a process in which centre-right liberal feminism has played some role).

The trouble is that treating such a cultural process as some form of social hygiene threat to be dispatched with a button deepens not only the process but also renders our interpretive response all the more shallow. We need more complex engagement and argument, not less, with what’s going on, and there is no button for that.

I love Guy Rundle!

Seconded!

I read through the reports on the Criado-Perez/Creasy twitter storm, culminating with bomb threats yesterday, with a kind of fascinated horror.

One could almost believe that we’re in the throes of an international mass hysteria (though that would be ironic, wouldn’t it?).

And high time that someone pointed out the common ground between misogyny and homophobia (or should that be gynophobia and homophobia, or mishomony and misogyny?)

‘Onya, Mr Rundle. It confirms the opinion that Twitter need not be part of my life.

Consider also that the eff word has been over-employed and, consequently, weakened in the past decade. Young men speaking amongst themselves seem incapable of uttering a sentence without using it at least once – and I don’t mean a sentence constructed in anger but any conversational sentence. Eff has become commonplace, passe, tired, hackneyed. Therefore the time is ripe for another shock word to come into inappropriate over-usage, ergo ‘r@pe’. Once its potency is eventually lost what next?

Honestly – does any sane person really object to Jane Austin being put on a bank note? Pre twitter/internet the village idiot was restricted to the market place and the trouble maker just caused a bit of localised mischief. Now these people who most likely are either deranged or just like “stirring things up” are given a world-wide prominence. They must be laughing their brainless heads off. Has anyone thought that ignoring the morons might get a better result?

While a button to report abuse on twitter may be lame it is a lot better than telling the victim of misogyny to shut down her account, thereby making the victim doubly victimised.

Certainly it is saying that women should just shut up – as happened to Julia Gillard when she dared talk about misogyny. She was the problem not the men who kept on talking about a gender war. A little like saying that protestors who get shot are at fault for getting in the way of the bullets. How easy it is to be philosophical about threats and abuse experienced by women.

Guy Rundle would be far more worth reading on this topic if he said this kind of behaviour is not cool but is reprehensible. That is what men need to tell each other. As it is we have no idea whether sexual violence is on the increase or decrease because it is never widely reported because the first offence is compounded by the court experience. The low rate of convictions is compounded by the low rate of prosecutions and reporting. Time for Guy to have his consciousness raised so he can avoid this kind of patronising and shallow analysis.