The haste of the Attorney-General’s department in seeking to push through a data retention regime prior to the 2010 election ended up derailing the proposal, and media scrutiny and a Senate inquiry forced a change of tack from the department toward public consultation — which the Labor government baulked at.

The timeline of the push by AGD for mandatory retention of Australians’ telecommunications and internet usage data has become clearer from documents obtained by Crikey under freedom of information laws.

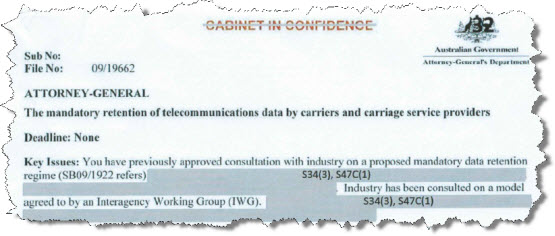

Yesterday we showed how AGD had begun pushing for a two year data retention regime almost as soon as Labor entered office, and the development of a proposal and secret consultation with industry was approved by the Department’s executive and the former Attorney-General Robert McClelland, who sought the approval of former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

After McClelland gave his approval to industry consultation in mid-2009, AGD undertook two rushed consultations with industry (the Pirate Party FOId those consultations; we examined them in February) at which industry raised a range of both technical and cost concerns. Despite failing to resolve industry concerns, it appears that just before Christmas 2009 AGD sought McClelland’s approval to develop a cabinet submission on data retention, and in May 2010, following another meeting with industry, the Department sought his approval, by June, to circulate a draft Cabinet submission on the proposal.

Both of those minutes are almost entirely redacted. Fortunately, however, AGD has made a mistake in its redactions. In 2011, Sean Parnell of The Australian FOId data retention documents as well, and he obtained another minute from October 2010, after the government had scraped back in, referring to the May minute. Crikey received the same October minute, with a key section redacted. But AGD failed to redact the same section in Parnell’s document, and that crucial omission explains the December 2009 and May 2010 minutes. “You approved the release of an exposure draft of the cabinet submission outlining a mandatory data retention regime in June 2010,” the October minute obtained by Parnell says.

That brief, again by Assistant Secretary Catherine Smith, goes on to state “a draft cabinet submission was circulated as an exposure draft in June 2010. Comments from other agencies indicated that further development of the regime was required in order for agreement to the proposal to be provided. Main concerns related to the financial impact of the proposal on industry and government, competitive issues and the impact of the proposal on small business.”

That is, other departments derailed AGD’s push for a pre-election decision to establish data retention because AGD had failed to put together an acceptable proposal or address industry concerns. They rushed it, and paid the price.

Meantime, AGD faced other problems. News of its consultations with industry had leaked in June, and FOI requests had begun coming in from the media. The department was able to fend off most of the FOI requests under the exemption for material for the “deliberative processes of the department and the government”. “The release of the information may have caused unnecessary concern,” Smith told McClelland.

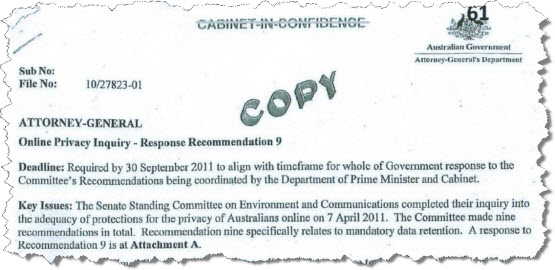

More seriously, in June, Greens senator Scott Ludlam had responded to the revelations by initiating an inquiry by a senate committee into the adequacy of protections of privacy online. Ludlam’s inquiry clearly worried AGD. “Media articles have indicated that Senator Ludlam will be seeking the censored documents, and all related documentation to be released publicly in an uncensored form.” The department would have to appear at the inquiry and respond to the committee’s report.

AGD then took, for it, an unusual decision, and a commendable one: it proposed to McClelland that they drop the secrecy and pursue a:

“… more open, transparent and consultative approach to be undertaken to acknowledge the public interest in the proposal … this approach will ensure that any public discussion is properly informed.”

But by this stage the government had taken fright. McClelland didn’t approve the department’s proposal to develop a public discussion paper, or if he did, it was never submitted to him for approval. AGD continued to consult with industry, without making much progress in resolving concerns.

The inquiry initiated by Ludlam reported in April 2011, with a recommendation calling for an “extensive analysis” of data retention and appropriate accountability measures. AGD’s focus then switched to trying to pull together an appropriate government response to the recommendation. In September 2011, five months after the inquiry report, Smith again briefed McClelland, asking him to approve a response that committed to an “open, transparent and consultative approach” that “acknowledges the public interest in these issues.”

No dice. The draft response went nowhere and in December, McClelland was replaced as AG by Nicola Roxon. The government eventually responded to Ludlam’s inquiry — in November 2012, by which time Roxon had initiated an inquiry by the Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security. The text was almost exactly what AGD had proposed more than a year earlier. Roxon had eventually picked up the Department’s idea of a public discussion paper, but that ended up being so ineptly handled that it contributed to the nixing of data retention altogether by Roxon’s successor, Mark Dreyfus, as another election loomed.

Lessons from all this? There’s a pretty important one: it was the leaking of news about data retention consultations, the willingness of the media (including The Australian) to seek documents and the determination of Scott Ludlam to pursue the issue in the Senate, that forced AGD to propose a more public process than the one they had previously pursued. It also spooked the government into inactivity on the issue. It’s possible that if other departments hadn’t been too concerned about AGD’s initial cabinet submission in June 2010, the proposal could have slipped through and been endorsed by the government. But once that opportunity was missed, the growing public focus on data retention was critical to stopping it — for now.

Good series on data retetniont following from yesterday. This article demonstrates how important journalism is to keeping governments and bureaucrats honest. It is a never-ending fight and a responsibility that cannot be taken lightly.

Agree with bluepoppy, but journalism in general, no. But at least the media did attempted to obtain documents in relation to the issue.

A key factor is the determination of the AGD to force it through. They are relentless and that begs the question of why, when the data retention proposals are clearly not in the public interest.

The question of who the AGD are representing is compelling. If it’s not the Australian public then who?

Many thanks to Bernard Keane and Crikey for pursuing the FOI docs.

This also demonstrates how valuable a cluey parliamentarian can be even in opposition, and what a loss it will be if Senator Ludlum does indeed lose his spot in WA.

@Murray Thomasie.

AGD is responsible for ASIO which in turn is in lock step with the NSA and GCHQ through our own DSD. I would put money on it that it is an ASIO initiated action which has been enthusiastically taken up by AGD, all in the name of security.

And as all those agencies are protected by legislation that makes public scrutiny impossible we probably will never know as the buck will stop at AGD. Makes a mockery of democracy in my opinion.

Could the NBN be the governments long term solution to the data retention problem?