In the frenzy surrounding development of New South Wales coal seam gas there seems to be a rather large lack of focus on how domestic demand for gas might actually go down, rather than up.

A number of people who participate in the energy policy debate don’t seem to have caught up with the fact that Australia’s energy demand growth has tailed off in the last few years while economic growth has continued. The chart below illustrates the Australian Energy Market Operator’s 2012 forecast for Australia’s eastern states gas demand, out to 2032. What we can see is a huge spike in gas demand associated with the export of LNG, but Australia’s domestic demand barely grows.

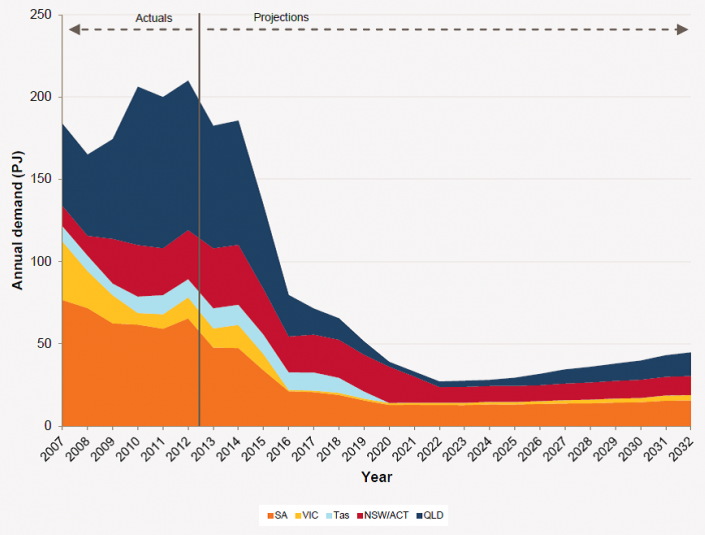

If we exclude LNG demand and delve another level down into eastern Australia’s domestic demand for gas by state (illustrated below), we see that, in fact, demand for gas has been declining since 2008 across every state other than Queensland. AEMO expects this decline to continue for much of this decade.

Eastern Australia domestic demand for gas (LNG demand excluded)

Source: AEMO (2012) Gas Statement of Opportunities

The fact that gas demand is declining for all states dependent on the South Australian Moomba and Victorian Longford gas processing plants makes one highly sceptical there’s not enough supply infrastructure in place to service NSW, without development of their own CSG resources. These processing plants and the pipelines that transport the gas have been sufficient to supply demand in the past, so given demand is declining they should be sufficient for the near-future.

While the main sources of gas in the Cooper Basin in Central Australia and Bass Strait, between Victoria and Tasmania, are getting long in the tooth, rising prices for gas and improved drilling technology means there is plenty of gas left that is worthwhile to extract.

This is not to say NSW should not develop its CSG, more that a supply crunch seems incredibly odd. It would mean gas producers suffered from a major failure of foresight, or neglected the known needs of domestic customers, to supply the export market.

Last week I caught up with Santos’ head of Eastern Australian operations, James Baulderstone. I asked him how — given demand in states apart from Queensland is declining and the Cooper has plenty of life left — Santos could find itself without enough gas from Moomba to meet NSW demand? Had they badly overestimated the amount of gas they could get out of Queensland coal seams to meet LNG export contracts, leaving them scrambling to find enough gas to meet their LNG contracts?

Baulderstone said it was more a case of failing to anticipate NSW government regulation over CSG extraction. When they acquired Eastern Star Gas in 2011 they had access to 1200 petajoules of CSG reserves in NSW, while NSW annual demand is about 140 petajoules. Therefore they felt they could afford to send more of Moomba’s output to LNG while still leaving NSW adequately supplied.

But it’s probably fair to say Santos has also faced challenges with securing enough gas from its Queensland CSG acreage. Since it committed to constructing its two LNG trains in late 2010, Santos has had to enter into agreements to secure gas from others, particularly Origin Energy. In 2012, Santos halved what is known as its “2C” gas available from the Queensland CSG acreage from what it had estimated the prior year. In addition it has sought government approval to expand the number of gas wells in its own acreage by 6100, from the original approval of 2650 wells. Baulderstone acknowledged that Santos aims to contain the rate at which it is expanding drilling in Queensland to ensure it keeps the local community onside. Access to gas from Moomba helps them to do this.At the same time, it seems a number of large gas consumers had their own problems with foresight. It was widely assumed that in the period leading up to LNG plants becoming operational, gas producers would have to ramp up gas extraction. This ramp-up gas would mean the market would have a temporary oversupply of cheap gas. So gas customers held off on contracting, expecting they’d get cheap gas. But it hasn’t materialised as assumed.

On top of this, it’s also important to consider that with the withdrawal of the carbon price, demand for gas in power generation is highly likely to decline. AEMO in its 2012 Gas Statement of Opportunities, produced an alternative gas demand forecast where the carbon price was repealed. The chart below illustrates the demand for gas in power generation would plunge from 2012 levels by almost NSW’s entire annual gas demand.

GPG annual demand by demand group (slow rate of change scenario)

If NSW is very seriously short of gas under such a situation, then it’s likely more than one organisation is to blame.

*This article was originally published at Climate Spectator

There doesn’t have to be a shortage of gas for local consumers if the gas extracting companies would just stop selling the majority of their ‘harvest’ off to overseas customers.

In my opinion the need for CSG in NSW or anywhere in Australia is all about a few corporations wanting to make money by creating a demand. Australia is not short of gases for fuel we export enormous amounts of gas. There is no Federal requirement in place to keep Australian needs first. The energy we once used to manufacture and now export means we are effectively exporting Australian manufacturing jobs. The need for CSG is a beat up which I believe is putting at risk the long term expense of important primary production. Edward James

There won’t be a shortage of gas for anyone in Australia, but the situation where Australians pay less for natural gas than it’s worth can’t be expected to continue. And nor should it – there are far better ways of supporting our manufacturing industries.

The people pushing for CSG extraction in NSW are pushing the fallacious argument NSW needs CSG. Manufacturing industries are moving off shore because it is simply cheaper to manufacture items elsewhere. Our government has permitted the price energy not just gas to increase to such an extent many people can’t afford to use it. Those with no alternate have started going without. Those in manufacturing and value adding have taken their business out of Australia. Australia is actually exporting jobs. The cost of energy is being driven up by corporations and investors wanting higher returns on their investments. It has not become harder to extract gas, but borrowings used for investing have become a big factor in pushing up the asking price for product! Edward James

The real problem is the RBA setting interest rates too high, which has resulted in our dollar rising much higher than our balance of trade justifies. That’s a much more immediate threat to our manufacturers than high energy prices.

And value adding is nowhere near as valuable as it once was, as the Chinese have taken most of the value out of it.