There was another attack on city centre apartment towers in the Fairfax press on the weekend. These appear every few weeks, seemingly taking turns with the regular attacks on the perils of suburban sprawl.

Melbourne has the most active city centre apartment market in the country, so it’s no surprise columnist Shane Green argued that Apartment towers are killing the world’s most liveable city.

Mr Green thinks Melbourne will be “permanently scarred” by apartment towers. He says “we risk losing the essential fabric of one of the great Victorian cities of the world, as developers continue their reach for the sky”.

Drawing in large measure on a newly released report by two Monash academics (Bob Birrell and Ernest Healy: Melbourne’s high-rise apartment boom), Mr Green argues that:

- There’s an apartment boom in the city centre and it’s likely to go bust. We could be heading for “a glut in the market that could extend for the rest of the decade”.

- There’s a disconnect between “an investor-driven apartment boom, mainly led by overseas players, and Melburnians’ real housing preferences”.

- The proliferation of apartment towers means the “creative class” vision for the centre of the city as “a place of work, recreation and residence in almost equal measure” is being lost.

- Most of the “bottom end” apartments are “little better than dog boxes”.

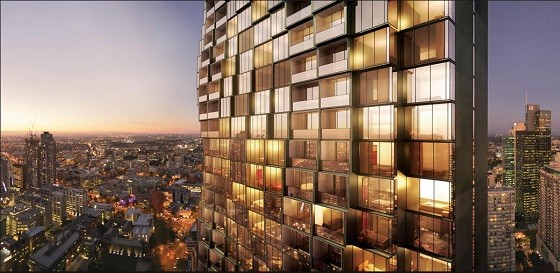

- Apartment towers are transforming the city skyline into canyons of glass and concrete. Melbourne could become “Hong Kong without the spectacular setting”.

It’s common for the media to assume that all approved apartment developments will be built, but it’s not true; developers respond to both demand and supply signals. But even if there were a “glut” in the city centre it’s not something that the rest of us should be unduly concerned about.

It’s the role of investors to take risks and reap the rewards or, as Mr Green fears, suffer the costs. The latter is what happened with financially troubled projects like Brisbane’s Clem 7 and Airport Link motorways, and Sydney’s Cross City motorway and Airport rail line. The investors took a bath but the citizens still get to use the built infrastructure. An over-supply of apartments should mean lower rents and prices.

Nor is there any reason to be especially worried that a high proportion of the demand for new apartments is coming from investors, whether domestic or foreign. Investors provide accommodation for renters, who comprise a large share of city centre residents.

It’s sometimes said that overseas buyers are more likely to leave their dwellings unoccupied for very long periods than local buyers. The vast bulk however have a very strong incentive to let their units so they can get a return on their investment.

The data doesn’t suggest there’s a big problem. In 2011, 14% of dwellings within the City of Melbourne LGA were unoccupied on Census night; that’s not wildly different from the figure of 9% for the metropolitan area or 11% for all of Victoria. In any event, vacancies primarily arise for a range of garden-variety reasons, e.g. changes of tenants, or residents away on Census night.

Deciding if an apartment is a “dog box” is a call that should be made by those who are contemplating living in it. These aren’t social housing tenants who have limited choice. They’re overwhelmingly young, one or two person households with the wherewithal to pay off a mortgage or a hefty rental.

They’re knowingly choosing to trade-off space for proximity to the enormous opportunities offered by the city centre in terms of jobs, education, culture and entertainment. It’s an easier choice if it’s known it will be temporary – the vast bulk of those living in studios and one bedroom apartments will very likely choose to move on to more spacious housing (though not necessarily detached suburban houses) at a later stage in their lives.

And they’re doing the rest of us a big favour. By creating demand for new dwellings, these residents reduce the pressure on housing prices elsewhere in the metropolitan area. Moreover, their way of life – e.g. small living spaces; low levels of car ownership – is especially sustainable. Because the new towers they live in are in the city centre, they require less in the way of additional taxpayer-funded infrastructure.

The claim that the proliferation of towers undermines Council’s creative class vision is puzzling. I think they have the contrary effect – they increase the population in the centre (which is still much smaller than the number of jobs) and attract the sort of highly skilled workers sought by city centre businesses.

Heritage controls are now much stronger than they were when high-rise office buildings started to sprout in the CBD, but I agree that the impact of towers on the skyline is a legitimate concern, as are related issues like how far towers are from each other; the potential for solar access; and possible wind effects.

But it’s also important to recognise that high rise has long been the established built form in the centre of the city. It’s that very high density that warrants the extraordinary level of public subsidy for infrastructure like the rail system.

The primary objective should be to ensure new towers function well at street level. I expect there’s room for improvement, but getting that function right is largely an issue of design and regulation, not a matter of rejecting higher density or greater height outright. Decisions need to be made with an appreciation of the economic, social and environmental benefits of city centre living.

I think the reference to “Hong Kong” cited by Mr Green is unfortunate. Residents of city centre high-rise in Australia tend to be small households, not families; they’re mostly well-educated, not average workers; and they’re not locked in to living in a high rise apartment all their lives. Indeed, for the same money they can choose to live in a much larger detached house in the outer suburbs if they want.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.