Investing in big urban transport infrastructure projects, especially motorway and rail projects, is the common response to the growth pressures faced by our major cities.

Sydney’s population is expected to grow by 1.3 million over 2011-31 i.e. from 4.3 million to 5.6 million. It will require an additional 545,000 dwellings and 625,000 jobs.

Melbourne’s population grew by 600,000 over the last decade. It’s projected to increase from 4.25 million at present to 6.5 million by 2050.

But big transport projects are extremely expensive and Governments at best only budget for one every five years or so. It’s also not clear that all big projects provide a significant improvement outside their immediate area.

Consider for example Stage 1 of the East-West Link motorway proposed for Melbourne’s inner northern suburbs. It’s expected to cost $6-8 billion to construct and may monopolise new transport infrastructure spending for some years.

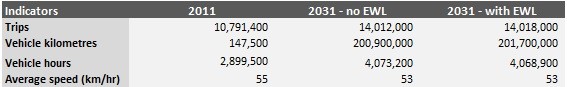

The first exhibit compares key indicators of forecast metropolitan-wide light and heavy vehicle road travel in 2031. It uses data from a report, East-West Link Traffic Impact Assessment, prepared by consultants GHD for the Linking Melbourne Authority.

It shows that building the East-West Link would increase the total number of trips on a weekday in metropolitan Melbourne by 6,000 compared to the no-build scenario. It would also increase total metropolitan travel by 800,000 km per day and reduce aggregate travel time by 4,300 hours per day.

These aren’t trifling changes; for example, if time is valued at (say) $50 an hour, the economic value of the forecast saving in travelling time would be nearly $80 million p.a. by 2031 (1).

But when looked at in the context of total metropolitan travel, the impact of the East-West Link would be decidedly modest. The number of trips in Melbourne would increase by just 0.04% (i.e. by four one hundredths of one percent); kilometres of travel by 0.4%; and aggregate travel time would reduce by 0.11%.

Whether or not the East-West Link is built will barely have any effect on the large changes in metropolitan-scale travel forecast over the period from 2011 to 2031.

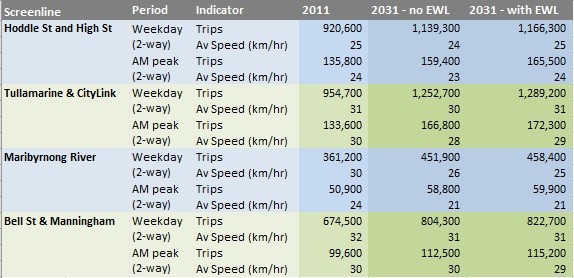

There would be much bigger changes at the regional scale but they’re relatively modest too. The second exhibit (see below) shows the East-West Link would increase traffic flows and average speeds at key locations within the orbit of the proposed motorway by only 2-4% relative to the no-build case.

Speeds on the East-West Link itself would be much faster in the off-peak (e.g. average 20 minute saving from Chandler Hwy to CityLink, with reduced variability) but the motorway would hardly be the “game changer” for the city as a whole the Premier claims it will be.

This isn’t just a roads issue; there’s a similar story with some proposed rail lines. Consider the Rowville rail line promised for Melbourne’s outer south-eastern suburbs in the new metropolitan strategy, Plan Melbourne.

It’s likely to cost at least $4 billion to construct but by 2046 would only increase public transport’s mode share in the metropolitan area by 0.1%. Moreover, 57% of patronage would be siphoned away from other rail lines and it would reduce the number of car trips on a typical weekday in 2046 by a trifling 15,000.

Modelling for the Doncaster rail line, which is also promised in Plan Melbourne, indicates it would have virtually no impact on public transport’s mode share at either the local or metropolitan scales.

As discussed here (Does this freeway make any sense?; Is investment in transport a game changer?), adding a new link to a mature and well-developed network will generally only yield a small improvement.

Forecasts like those cited above suggest it’s worth asking if governments will be able to deal satisfactorily with the scale of growth anticipated for our cities just by building a major new piece of road or rail infrastructure once every five years or so. It’ll be an even more pertinent question if they continue to select projects for primarily political reasons rather than good policy reasons.

Governments need to find ways to increase the infrastructure build rate without threatening other important areas like education. They also need to ensure they build the best projects.

Most importantly though, they need to think much harder about how to make the huge stock of existing metropolitan-wide infrastructure work better e.g. by implementing road pricing. Just building major infrastructure projects isn’t likely to be enough.

_________________________________________________

- It’s impossible to know without seeing the detail in the business case, but in light of the Government’s advice that the BCR for East-West Link is 1.4, I’d have expected bigger time savings than suggested by 4,300 hours in 2031. Perhaps the savings in other areas like vehicle operating costs, accident savings and “wider economic benefits” are large enough to get the BCR into positive territory?

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.