New data on the declining efficiency of Australia’s financial services sector suggests the federal inquiry led by David Murray has its work cut out for it in ensuring Australia’s vast pool of wealth is managed effectively.

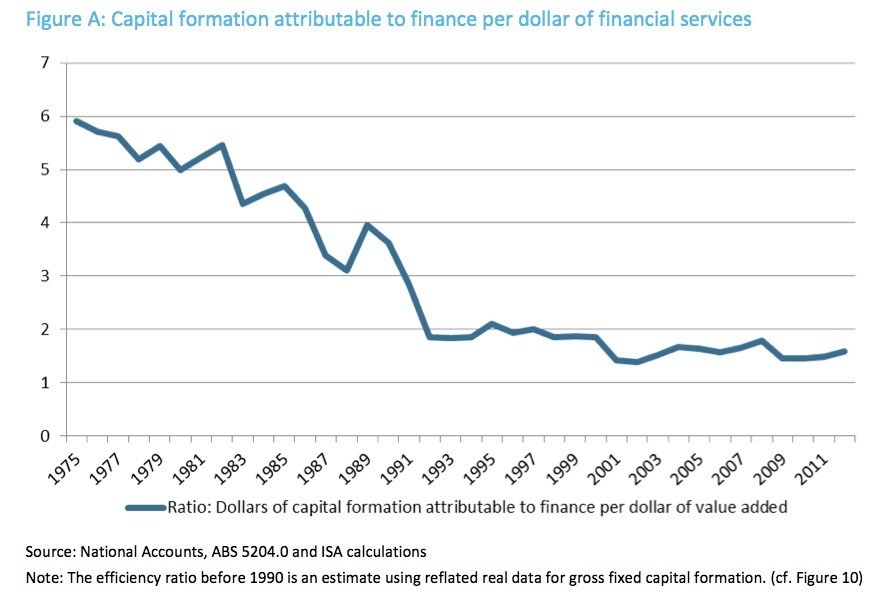

A new study from the Industry Super Association reveals the big decline in the efficiency of capital formation in Australia’s financial services sector over the last 40 years. In particular, over the last 20 years the level of capital formation for every $1 of resources allocated to the sector has fallen from $3.50 to $1.50.

It’s crucial that this issue is investigated by the inquiry into the financial services sector, recently announced by Treasurer Joe Hockey and headed up by ex-Commonwealth Bank CEO Murray. Financial services are now not merely an industry that plays a crucial role in facilitating the real economy, increasingly it is the real economy, with the big four banks producing annual profits of around 2% of the economy.

What’s being measured in the Association’s report is complicated, but in essence it’s the amount of labour and capital resources in the finance sector compared to the level of gross fixed capital formation in the economy, minus capital generated by firms themselves from profits, and minus foreign capital.

It’s not a productivity measure but more an indication of how much additional capital the growing level of resources in the finance sector is producing for the economy — the ability of our financial services industry to turn savings into productive investment.

That means we’re not making the most of the giant savings pool we’ve put together since compulsory superannuation was introduced, and which is going to continue growing rapidly even as baby boomers start drawing down their super (and at a time when the resources-led investment of recent years has peaked). We are getting less bang for each buck of super saved and invested, when everyone wants more; superannuants, fund managers (for their fee income streams), governments, the Reserve Bank, companies and shareholders, who are super funds.

It’s a kind of negative feedback loop: our use of super savings is getting less efficient and less productive the more the pool grows.

Reasons for the decline in efficiency are unclear, but one factor may be the rapid growth in employment in the indirect financial services sector compared to flat employment elsewhere in the industry: employment in auxiliary financial services, which includes financial planning, mortgage brokers and credit card services, has far outpaced growth in areas like insurance and super and straight finance. From about 1995, auxiliary finance services employment surges far ahead of employment in the rest of the finance sector, possibly driven by the staggering $20 billion per annum worth of fee income generated by superannuation, the bulk of which is in the retail super fund sector.

However, the longer term figures suggest a big fall in efficiency seems to have occurred with financial deregulation under the Hawke government in the 1980s. As the report notes, this is counter-intuitive — deregulation should improve efficiency, at least according to advocates of free markets. One possible explanation is that Australia’s financial sector initially struggled with deregulation. Some banks tried to expand aggressively domestically and offshore, with disastrous results. Several institutions ended up collapsing or being taken over in the early 1990s.

The 1980s also marked the start of financial services as a genuine mass market industry, rather than a boutique industry shaped around a narrow range of services. There was suddenly greater choice for investors and for institutions, and plenty of poor decisions resulted. Efficiency also ratchets down after each recession or disruptive financial event — eg. the 1990s recession, the 2000 slowdown and the GFC.

The end result of this long-term transformation in finance can be seen in the shape of our four big banks — close to 30% of the stockmarket’s value, or looked at another way, close to a quarter of our GDP. They are too big to fail, and prudence dictates they will have to hold more capital as a result. According to some, that will result in still greater inefficiency of capital use.

And it’s no accident that the dominant position of the big four banks and finance has been as a result of the growth of our pool of superannuation funds ($1.6 trillion). Investors of all sizes look for the most efficient use of their money and the low-cost, easiest way is to change yield and fat dividends by investing in the big four banks — close to $20 billion a year in dividends and billions more in capital gains. It’s money for old rope.

In its latest annual report on Australia’s productivity performance, the Productivity Commission found that finance (including insurance) is now the single largest sector of the economy at 11.5%, just above mining on 11.2% (in 2011-12). More importantly the Commission pointed out that finance’s productivity (MFP) performance had worsened notably since 2007 and slowed to negative 0.2% growth over the period 2007-08 to 2011-12, from 4.4% positive growth in the period 2003-04 to 2007-08.

But this is all speculation. A more sophisticated analysis awaits, and the Murray Inquiry should perform that role.

Lifting the performance of the financial sector in converting savings to investment is every bit as critical, and probably much more so, to our economic prospects, than the obsession with industrial relations, or a budget surplus, or the Aussie dollar that dominates what passes for economic debate at the moment.

Not surprising, given that large parts of the financial services industry is a giant con!

Great swathes of it could be redeployed to useful jobs with no ill effect or anyone noticing, in fact.

This is a difficult and potentially confusing area of analysis. The graph suggests two demarcated time periods:

1975-1992 and 1992-2012. The latter period shows a relatively minor fall in the ratio from around 1.8 to 1.6 while the former period shows a major decline from 5.9 to 1.8. Moreover the latter period also shows a small uptick between 2009 and 2012 (1.5-1.6). So maybe we’re comparing apples with oranges inter-period. The financial services sector in the first period would have been relatively primitive with traditional banking being a larger proportion of the sector, and with little or no internet technology. The second period saw enormous growth of superannuation and sophisticated trading in derivatives etc. aided by the internet. What is being measured is the purported link between value added in the sector and capital formation. I think this is of limited use inter-period because of the huge changes in the nature of the sector. Should there be a trend towards super fund investment in infrastructure, I would expect to see a steady improvement in the ratio as additional resources required (value added) should be relatively small.

Very good initial analysis into a system any thinking person always had suspicions with. A bloated financial system with mandatory inflows is no reipe for efficiency. Guaranteed bucket loads of money pouring into institutions, with stuff all performance standards and all they do is bet the billions on the stock markets and pocket their 10 per cent as middlemen who add no value what so ever.

But alternatively we don’t want their productive investment in public infrastructure because they demand an excessive return and corrupt the process of choosing which infrastructure to build. Governments can borrow much cheaper, so why use Those funds? They are a very expensive and inefficient way to fund people’s retirements. You are better to raise taxes to pay a higher basic pension, it is more efficient in the long run. No financial parasites in the chain.

Proponents of conservative economics have for years been keen champions of the efficiency dividend in the public service and education and health sectors. I look forward to those advocates’ calls of for similar cuts to the perks and privileges of the banking sector – what’s good for the goose…

A very good call for a part of the Murray review.

Will it be included?

Like others I wonder. The industry is bloated, over paid and adds no value for its customers. Or it seems the economy as a whole.

It is really a case study in the fallacy of privatising things. Supposedly for efficiencies! But without accountability (have you read your superannuation statement?) and transparency, which governments are required to do, we have simply given 10% pa on rivers of serannuation gold to the finance sector for nothing.

BTW have the financial advisors been forced to gain a Cert 3 qualification in providing advice or have they been able to defer so that this government will not require it?