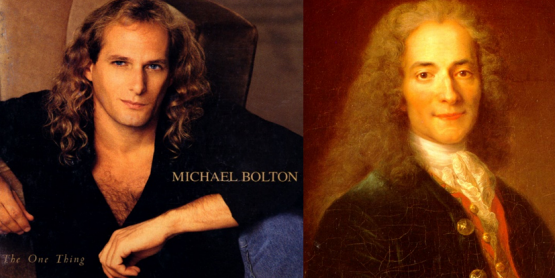

Just like books, forms of government and haircuts, protest has a history of styles. The style of liberal democracy unfolded in France, for example, thanks in no small part to the books of a man who had the same haircut as Michael Bolton. While Voltaire was legitimising future freedoms — including that to wear a reverse mullet in public — one of the protest styles of his time and place was the Grain Riot.

These Grain Riots were an early industrial flashmob: the hungry rural poor would descend upon a market for a morning of synchronised shoplifting. Only bread or grain was stolen; fancier goods like cake remained strategically untouched. The food, whose cost was now contingent on the emerging market economy, was then bought and sold by the rioters to each other at a just price.

Inflation might have produced famine, but it also gave us French peasants with a cunning protest style. Late capitalism has produced richer peasants and with us, milder expressions of dissent. The old revolutionaries had economic uprising; we can buy Awareness ribbons.

Of course, Awareness is not all we have in what sociology calls a repertoire of contention. The developed world, the digital world and dependent nations all continue to produce new and noteworthy forms of protest, which I hope to canvass in this weekly diary. But there is an awful lot of Awareness about. The last months of the year are particularly bright with ribbons.

October is annually awash with the optimism of pink and, more lately, with the impatience of the breast cancer survivors it purports to assist. Not only are some commentators exasperated with the use of pink as a disingenuous marketing tool, others have become convinced that this month is less about awareness than it is obfuscation; many critique what they regard as bad medical information. One recent academic study that set out to examine the campaign’s effectiveness unexpectedly found that the pink brand made women perceive their risk of breast cancer as lower and tended to dissuade them from donating to breast cancer charities. While it is almost certainly true that the month affords comfort to many breast cancer survivors, it is also almost certainly untrue that it does much more than that. October is a month where some women get to feel individually good.

And November is a month where men are required to feel individually bad. This month’s signature colour is white, and its chief Awareness moment occurred this past Monday with International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. Also known as White Ribbon Day, this campaign which urges awareness in men receives broad and uncritical attention from football teams and and the Murdoch press.

Of course, only a nut and/or a men’s rights activist would critique the objective of this campaign. Every reasonable person wants to diminish the incidence of violence in the world. But, perhaps not all reasonable people would agree that “Awareness”, such as it has come to exist, is an effective way to achieve this end.

Awareness is less a form of social protest, perhaps, than it is a form of introspection. Inward-looking may not be a great problem when it comes to thinking about cancer. Here, the act of liberating the individual is, at worst, a feel-good indulgence. In considering the matter of their own potential for violence, however, subjects might be best swayed away from solitary thinking.

While it might seem noble for a man to wear the ribbon and declare that they are deep in thought about the matter of their own violence, it is also anti-social. Given that violence itself is an anti-social expression, awareness seems a bad choice.

Take the oath, the website promises, and you can end violence toward women. Such is the power of one.

The Awareness movement is not concerned with the social but with the self. Here, the individual is responsible for taking the “oath” not to physically harm women. As Awareness has it, there is not greater or more forceful authority than the individual; problems and their solutions all start and end with introspection. A less forgiving psychologist might diagnose this as narcissism.

The news that NSW police wore white ribbons yesterday to the trial of murderer Simon Gittany was enormously well-received on traditional and social media. While the flourish may have comforted those grieving the victim, Lisa Harnum, it likely does little else but call the morality of the NSW police into question. That those professionally sworn to serve and protect citizens from harm would take an extra oath is curious.

This is Awareness: an anti-social form of social action in which there is no higher authority than the individual. Not even the NSW police.

Townspeople of the 17th and 18th centuries stealing bread are, rather arguably, more socially connected in their protest than these officers or the well-intentioned ambassadors of breast cancer. The rabble sought to defy social order. The awareness campaigner seeks only introspection.

So this Sunday on the 25th anniversary of World AIDS Day — the bright red, near-forgotten antecedent of all this Awareness — perhaps we should not pause to reflect. Perhaps we should just act to steal, buy and sell anti-viral drugs to those who most urgently need them. Awareness is the cake we can ill-afford to eat.

* Helen Razer describes herself as a semi-professional bellyacher and Marxist of convenience

Quote: “Awareness is less a form of social protest, perhaps, than it is a form of introspection. Inward-looking may not be a great problem when it comes to thinking about cancer.”

Helen,

I guess that my interpretation of “awareness” in this context is a bit naïve. For me there is no introspection, but the message seems to be more along the lines of:

Be aware that the noises coming from the house or flat two doors down is a case of domestic violence, and that you should “stand up” and do something about it, whether that is to call the police or knock on the door and try to stop the situation escalating further.

On that level it seems like a worthwhile campaign to me, although I don’t think it will realistically put a stop to the violence.

Firstly fantastic to see Ms Razer back & on a regular basis. Thank you goddesses of excellence in writing & analysis. On this particular topic I find myself in even more agreement than is usual. The Awareness movement is not just anti-social but in some cases can in fact add to the danger faced by those most at risk

Good article Helen. Only if the awareness is the first step to greater education and then to action is it a value to society.

Well said, Ms Raze (if I may). And I love the new header to your now regular article.

Easy to agree with everything Razer says. All these Ribbon days are not designed for the intellectual elite. As well, many of us ordinary folk eschew them as embarrassing on a personal level. They are easy to mock, but the real question is are they harmful. And can societal pressures actually have an effect for the good?

(In her book ‘Smile or Die” Barbara Ehrenreich writes on how disturbing she found the Pink Ribbon movement after she was diagnosed with cancer).