Making public transport “free” by abolishing fares is one of those perennially popular ideas, but very few cities around the world have actually done it. Various propositions are cited to support it; for example that it would be more equitable, or that public transport, like public education, should be free as a matter of principle.

The most common argument, though, is that it would make travel by public transport much more attractive and consequently lead to significantly lower car use. That in turn would reduce the negatives associated with cars, like traffic congestion, pollution and emissions.

Proponents argue the impact on the budget would be offset to a considerable degree by lower collection and enforcement costs. Some also contend that taxing those whose properties appreciate in value due to public transport infrastructure would provide a replacement revenue stream.

An official figure for farebox revenue is hard to come by; as explained here, my conservative estimate is that it was $650 million in Melbourne in 2011 (after netting out lower collection and enforcement costs).

That all sounds good, but here are ten issues to consider when assessing the wisdom of abolishing fares:

- The absence of fares doesn’t mean public transport costs nothing. Revenue still has to be found to pay the cost of running the system. The debate about “free” public transport is really a question about who pays.

- In the context of State budgets, $650 million p.a. is a very large sum of money to remove from the public transport system. It’s enough to operate around 30 SmartBus systems like Doncaster Area Rapid Transit (or, looking wider, to cover the recurrent costs of around 50-60 large high schools). As I’ve written previously, the rail system alone needs billions spent on things like improved signalling, track upgrades and duplications, more train sets, new rail lines, improved security, and much more.

- Public transport patronage is more sensitive to the level of service than it is to the level of fares. Investing $650 million in improvements like greater reliability and more frequent services would increase patronage by more in the longer run than the boost from eliminating fares.

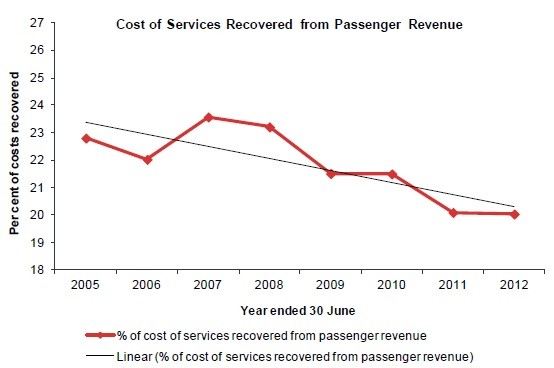

- Public transport users already benefit from very high subsidies. In Victoria, they only pay around a third of operating costs in fares. In NSW rail passengers only pay 20%; according to the State Auditor General, the average state-wide subsidy in NSW in 2012 was $1.57 for each bus trip and $10.01 for each train trip.

- Higher patronage generated by abolishing fares would increase operating costs and crowding without any offsetting increase in revenue. It’s inevitable there’d also be pressure to abolish fares in regional centres. The real cost to the state budget would be considerably higher than $650 million.

- Most of the extra patronage would come from current users making more trips. In the absence of a dramatic rise in the cost of driving, the potential of public transport to win trips away from cars is limited because outside of a small number of locations like the city centre (where congestion and high parking costs work against the car) there are few trips where public transport is as fast or as convenient as driving. The majority of trips to the CBD in cities like Sydney and Melbourne are already made by public transport. Even a big increase in patronage wouldn’t change mode share significantly. For example, the number of commuters travelling to work by public transport in Sydney grew by 35% between 1996 and 2011 (after many years of decline), but public transport’s mode share for the journey to work only went from 22% to 23% over the period. (1)

- The argument that fares could be replaced by taxing land owners is irrelevant. It’s just one of a number of ways that any initiative, of which free public transport is just one, could be financed. Indeed, value capture could be used to increase funding for public transport rather than as a replacement for foregone fare revenue.

- Assisting disadvantaged travellers would be addressed more efficiently by targeting assistance directly at those in need. It is neither necessary nor desirable to make public transport free for those with the resources to pay.

- The big winners would be those who work in the CBD and live close to public transport. They’re a minority – only around 15% of all jobs in the metropolitan area are within walking distance of Melbourne’s city loop.

- Removing any link between distance and price would encourage households to live further out where car use for the majority of trips is higher. It would also encourage further long distance commuting from regional centres.

Public transport has a long history of struggling for funding in Australia. There are a number of reasons for that. One is that it only carries a relatively small proportion of all trips in Australia’s major cities (around one tenth averaged across the capitals). Another is because users don’t make a big contribution to meeting operating costs (see exhibit).

Achieving a step-change in the level of public transport patronage will depend in part on offering a much higher quality of service. But by itself that won’t be anywhere near enough; the key issue is that unless the “price” of driving relative to public transport is increased dramatically (e.g. by congestion charging), public transport will continue to languish as a niche mode.

______________________________

- That’s because car use for the journey to work grew 21% over 1996-2011. That was a lot slower than the increase in public transport use but it was from a much larger base.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.