A new ABS statistical publication released this week says Australia’s capital cities are really packing them in. It shows population in capital cities grew three times faster over the last year than in the rest of Australia. (1)

What’s especially interesting is that the fastest growth in the country wasn’t in the outer suburbs of Perth or South East Qld but in the very centre of Australia’s second largest city. The number of residents in the diminutive City of Melbourne (36.2 sq km) increased 10.1% over 2012-13, from 105,402 to 116,431. (2)

Growth in some parts of the municipality was phenomenal. The number of people living in the CBD grew by 22.7% in the course of the year and the population of both Docklands and Southbank increased by 15%.

The pattern appears to be continuing. The number of approvals for multi-unit developments over three storeys in Victoria for the three months to February 2014 was 33% higher than it was in the same period last year

Not surprisingly, RMIT planning academic Michael Buxton voiced his familiar complaints in the media about the number of high-rise residential towers already built or planned in the city centre to accommodate the demand for city centre living.

According to The Guardian, Professor Buxton claims Melbourne is becoming similar to a high-rise Asian city and is losing its attractiveness as a result. He’s not the only one to complain that Melbourne is becoming like Hong Kong; see this article by Fairfax journalist Shane Green and this one by ABC producer Shane Ziffer.

Apart from the inscrutable “Asian” references, the usual concerns raised by critics are that high-rise towers dominate the skyline, cast shadows, generate winds at ground level, are too small, and in effect are “vertical sprawl”.

I think there are some important points to bear in mind in the debate about high-rise residential towers in the centre of capital cities like Melbourne:

- They’re a response to demand. If the supply were constrained it would increase prices and exclude many of those who want to live in the centre, starting with those who have the least financial resources.

- Part of the reason for the high demand in and around the CBD is that alternative housing options in most of the inner city and middle suburbs are limited by planning rules that constrain supply and raise prices.

- Higher housing supply in the city centre has a knock-on effect; it helps to lower housing prices elsewhere in the metropolitan area by absorbing some of the excess demand.

- City centre living scores highly on sustainability. Residents live in small, well-insulated apartments and, although they use electricity for elevators, they use sustainable ways of travelling.

- Residents save public spending on big-ticket infrastructure, especially on transport. They are more likely to walk, cycle or travel on trains against the peak than residents of other locations.

- The reference to Asian cities misses the mark. Unlike Hong Kong, only a tiny part of Melbourne is slated for high-rise towers. The vast majority of the apartments are occupied by singles and couples; not by families as they are in Hong Kong.

That’s not to say there aren’t the inevitable downsides. High-rise apartments are certainly “tiny” by the standards of suburban detached houses and some have bedrooms without windows (they use “borrowed light”).

But these are primarily matters for the buyers and renters who freely choose to live in them and who in most cases can’t afford anything bigger in such a sought-after location. These are not public housing tenants who have limited choice about where they live.

It’s true towers cast shadows and can generate unpleasant wind effects at times. These problems can and should be mitigated by design to some extent. But what’s most relevant is this is the CBD, not the suburbs.

The CBD has traditionally had tall towers to enable firms to reap agglomeration economies and permit mass transit to move huge numbers of workers in a small time window. The benefits of high density inevitably come with some compromises.

Some argue that instead of towers, Melbourne could achieve the same population density in the city centre by emulating the low rise built-form of historic Paris. It certainly sounds attractive, but this romantic notion overlooks the narrow streets and limited open space in Paris.

It also ignores the complexities of history, in particular the small size, disparate ownerships, different planning controls, historic protections, and existing values of land parcels in the city centre. CBDs are not greenfields or brownfields sites.

And back to the spectre of “Asian” cities for a moment, I note that his week Hong Kong topped the world rankings of the Arthur D Little Urban Mobility Index 2.0. Maybe we can learn something from Hong Kong?

There are design issues with some of the recent towers that need to be addressed, but in terms of the big picture of housing supply, the Government has got this aspect of it right. Whether or not its policies to boost supply in established suburbs make as much sense is less certain (see Will “protecting the suburbs” safeguard affordability?).

____________________________________

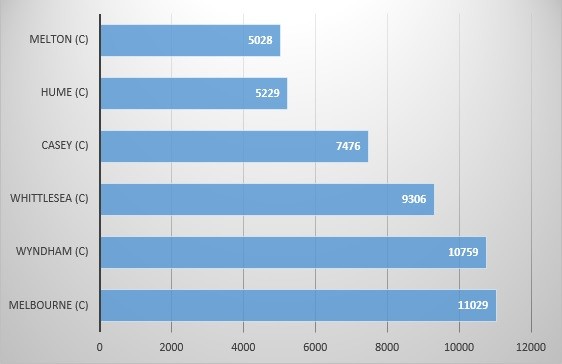

- The municipality with the next largest increase, the City of Wyndham on Melbourne’s western fringe, has an area of 541.6 sq km.

- The ABS’s media release emphasises the dramatic growth rates of the capital cities e.g. “Capital cities packed in more than three times as many new residents as the rest of Australia in the year to June 2013”. However it’s notable that the share of the national population in capital cities has increased very slowly: it was 65% in 1973 and 66% in 2013. Not really very dramatic; be wary of relying solely on percentage increases.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.