What if the basic assumptions leading to the Indian Ocean search for missing flight MH370 were seriously flawed? What if the jet is somewhere else, where no one has even looked?

An insight into what might be going on in the Canberra review of all of the evidence and analysis as to the disappearance of the Malaysia Airlines 777-200ER with 239 people on board on 8 March is provided by a very carefully written article in the The Atlantic.

The article is disturbing for a number of reasons, apart from the distinct possibility that it is largely if not completely right.

It reports on a lack of transparency or responsiveness in the Inmarsat company in relation to what read as soundly based queries as to its methodologies and inconsistencies in parts of its official analysis of the data one of its satellites collected from regular standby pings from a data reporting system on the missing jet.

Those pings were received at regular intervals before and during a flight that ended seven hours and 38 minutes after the jet took off on a scheduled five hours 50 minutes flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing.

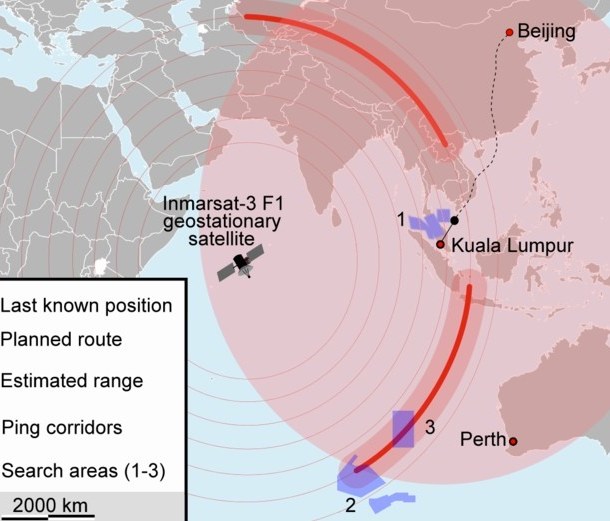

They provided the basis for the Malaysia decision to focus all search and recovery efforts on the southern arc of possible crash locations in the southern Indian Ocean south west to west of Perth, and which was later refined into a line of possibilities to the north west of Perth.

One of the authorities quoted by The Atlantic is Duncan Steel, a distinguished physicist well known and respected in Australian science, and well connected in our defence and astronomy communities.

If the analysis from Inmarsat does indeed have the jet that performed MH370 moving as fast as a car on an open road when it was supposedly just pushing back from the gate on the morning of its disappearance then there is a problem.

Reading The Atlantic article is also a reminder of the distinct change in language and emphasis from Angus Houston, the chief coordinator of the Joint Agency Coordination Centre early this week when the ministerial level tripartite talks between Malaysia, China and Australia in Canberra announced the data and analysis review that began in the Australian capital on Wednesday.

Houston was concise and firm as to his disappointment in the failure of the search to date to find a single piece of material evidence that MH370 crashed into the Indian Ocean.

However he was just as firm in the view that it was, on the evidence, somewhere on the more than 60,000 square kms of Indian Ocean sea floor broadly identified as being where the jet came down, which will be searched in great detail starting late this month or next, using larger, deeper diving equipment chartered from mining companies.

Even if the analysis of the satellite data is as flawed as The Atlantic suggets, that doesn’t mean MH370 isn’t in the Indian Ocean, and it doesn’t change the established fact that the jet was flying seven hours and 38 minutes after takeoff, when a last incomplete signal was received, most likely at the moment it crashed.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.