Australia’s mandatory helmet laws are back on the public agenda this week; cycling advocacy group Freestyle Cyclists is organising a 15 km helmet-free ride this Thursday from the venue of the Velo-City Global 2014 conference in Adelaide (although SA Police say they’ll escort the ride and won’t fine anyone who rides without a helmet, see here and here).

One of the many conference speakers, Danish cycling activist Mikael Colville-Andersen, raised the issue well before the conference started. He said last year that he’d refuse to cycle in Adelaide during the conference because of the mandatory helmet law.

I don’t ride bicycles in cities that have helmet laws. The world has been pointing and laughing at your bicycle helmet laws for almost two decades…Whenever a helmet law is proposed elsewhere in the world, which isn’t often, Australia is held up as the example of how helmet laws destroy urban cycling.

It’s a cycle planning conference so there’re many other issues on the program, but whenever cycling policy is discussed in Australia the helmet law usually gets raised. That’s fair enough if it’s a key constraint preventing cycling from flourishing in Australia; but is it? Is the law “destroying urban cycling”? Does it warrant being a high-profile objective of cycling advocacy?

I think the helmet law is unquestionably one of the reasons for the poor performance of bikeshare schemes in Australia, but I’m not persuaded it’s a major drag on cycling more generally in this country – I don’t think it even comes close. I want to explain my point of view, drawing in part from an article I wrote a couple of years ago, Mandatory helmet laws: does correlation mean causation?

There’s no doubt bicycle use in Australia is very low compared to countries like the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany where helmets aren’t mandatory for adult riders. But the law in Australia seems to explain very little of the difference.

The law doesn’t, for example, explain why only 1% of trips in the UK are by bicycle even though helmets aren’t mandatory in that country. That’s no better than here! Nor does it explain why cycling’s mode share is only slightly better in Ireland and Canada than it is in Australia, even though those two countries don’t have mandatory helmet laws. Whatever the explanation is, it has nothing to do with any legal compulsion to wear a helmet.

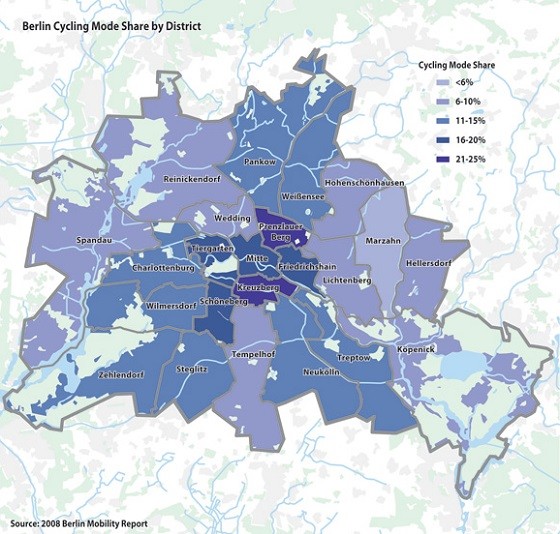

There are also enormous differences in the level of cycling between countries where helmets aren’t mandatory. The fact that bicycle use is more than twice as high in the Netherlands as it is in Germany – and nine times higher than it is in France and Italy – shows clearly that there are other highly influential factors affecting the propensity to cycle that have absolutely nothing to do with helmets.

Nor can helmet policy explain why bicycles capture 34% of trips in Munster, but 13% in Munich. Or why the corresponding figure for Groningen is 37% compared to 10% in Heerlen; or 20% in Bruges but 5% in Brussels; or 19% in Salzburg but 3% in Wien.

Pucher and Buehler argue the key reason cycling is so successful in many Dutch, Danish, and German cities relative to other places (not just Australia) is down to extensive systems of separate cycling facilities, intersection modifications & priority traffic signals, traffic calming, bike parking, coordination with public transport, traffic education & training, and sympathetic traffic laws. They also point to the positive way cycling is promoted.

The reason many cities in these countries have high levels of cycling isn’t because helmets aren’t mandatory; it’s because helmets aren’t necessary. They’re not necessary because subjective and objective safety is an order of magnitude higher than it is in Australia. The horse is in front of the cart.

Those who advocate repeal of the law invariably fall back on the argument that cycling collapsed in Australia when mandatory helmet laws were introduced in the early 90s. There was indeed a collapse – according to a Victorian ‘before and after’ study done at the time, bicycle use by 12-17 year olds fell 44%. However, cycling by 5-11 year olds fell by a more modest 10% and cycling by adults, while falling in the first year, was almost back to the pre law level by the second year (it doubled in metropolitan Melbourne).

Almost 25 years have passed – that cohort of young teens moved on long ago, taking their ideas of what’s “cool” with them (there was nothing cool about Rosebank Stackhats back in the day; Cadel was a kid; and who’d heard of le Tour?). The law simply gave a push to deeper structural changes that were undermining cycling by students e.g. the increase in private school attendance; higher levels of car ownership; the growth in dual income families; increasing traffic on suburban streets. (1)

Although the absolute numbers were miniscule, a NSW ‘before and after’ study done at the time found there was also a fall in cycling to work following introduction of the helmet law, especially in regional areas. The most plausible explanation is riders were largely blue collar workers who cycled because cars were expensive. Many worked in industries like food processing that are now much diminished, reflecting the general decline of manufacturing and the drift of population to the capitals and larger regional centres. This is a group who has largely vanished and in any event had different values to the professional urban demographic that shows the most interest in utility cycling today.

It’s impossible to be certain about the number of travellers who’re currently deterred from cycling by the law, although I accept there’re some who variously find helmets sufficiently uncomfortable, inconvenient, or uncool to deter them from cycling. (2) But other than in the case of bikeshare (which let’s not forget only represents a tiny fraction of existing and potential cycling), the kilometres of cycling foregone due to the law is likely to be very small.

That’s because not liking having to wear a helmet isn’t the same as not cycling. Travellers who’re prepared to put up with the myriad other inconveniences, like enduring cold, rain, wind, theft, punctures, danger, sweat, etc, aren’t likely to be deterred from cycling in large numbers because they can’t go helmet-free; cycling is just too attractive a proposition on so many other counts.

The upshot is that the social cost from deterred cyclists is likely to fall well short of the social benefits from the reduction in head injuries (see here and here) provided by compulsory helmet use. (3)

In my view, the public debate about the helmet law is a waste of energy because it’s got virtually no traction politically. So far as the public are concerned the law is common sense, like seat belts; 94% regard the law as a non-issue. (4) Ultimately, concerted opposition to the law distracts resources from the key issue – the danger, whether perceived or real, of cycling in traffic.

The gains to cycling from better infrastructure and better regulation of motorists are likely to dwarf any putative benefit from repealing the mandatory helmet law.

Update (9:00 am 29 May): There’s a thread discussing this article at Adelaide Cyclists.

Update 2 (2:00 pm 29 May): Anyone who doubts my contention that there isn’t much support for repealing the law should look at the tone of the comments on this article on Crikey’s Facebook page.

____________________________

-

In any event, virtually no one at present is advocating that children should be exempt from the helmet law.

-

I also acknowledge that some cyclists object to the “nanny state” telling them what to do, but while they resent it, it shouldn’t result in them cycling less.

-

It’s not just doubts about the size of the deterrent effect either. The social costs are usually overstated too. It can’t just be assumed that those who’re deterred by the law would sit on the couch all day and get fat; or that they’d all drive everywhere. We already know that most commuter cyclists would otherwise use public transport, not drive.

-

Re Mikael Colville-Andersen’s point, the big difference between us and other countries where there are calls for mandatory helmets is that the law has been in place here for almost 25 years; abolishing a law and introducing a law are not symmetrical actions. Also, proposing a helmet law in countries where cycling historically has a very high mode share is a very different proposition to what’s happening in Australia.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.