The spectacular oil-price crash following the Saudi-led decision of the OPEC cartel to maintain production — despite a glut and in the face of softening demand — has left peak-oil theorists in an awkward position. Wasn’t the cheap oil meant to be running out?

For many market-watchers, the rise of unconventional oil and gas in recent years — spurred by higher prices and improved technology, especially directional drilling and fracking — has rendered the so-called “peakists” irrelevant. In an influential 2012 piece, Business Spectator‘s Alan Kohler called the “death of peak oil“, sparking a terrific debate with one of Australia’s foremost peakists, Matt Mushalik.

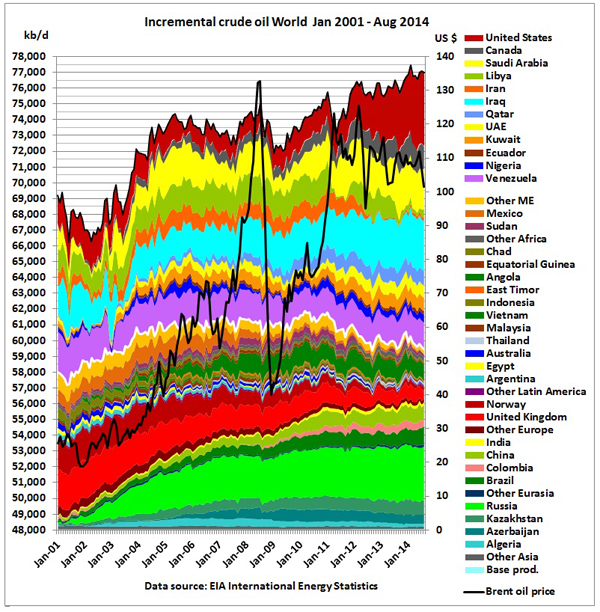

A retired civil engineer who is a member of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and who blogs at crudeoilpeak.info, Mushalik is a tireless correspondent to journalists and politicians, critiquing energy and infrastructure policy from his Sydney home. He also knows his stuff, compiling the fascinating chart below, which shows incremental crude oil production (that is, additional supply above a base level) country-by-country, based on official US data:

Mushalik explains: “When you look at the statistics, outside North America — excluding US and excluding Canada — crude oil production is basically flat, on a bumpy plateau, that’s a fact.”

“The way I see the peak oil story is that conventional oil peaked around 2006,” said Mushalik, citing as evidence similar comments made by International Energy Agency chief economist Fatih Birol to the ABC’s Catalyst program in 2011.

“The response of the system — I mean governments, banks and the oil industry — was twofold: firstly, quantitative easing started, [which] enabled the economy to pay for higher oil prices, and secondly, a certain percentage of quantitative easing money went into the oil sector as cheap money, hence the [rapid development of] shale oil and tar sands,” Mushalik told Crikey.

“After the GFC, oil prices went up again to US$110 for three years and that killed demand. That is why I’m saying the experiment of offsetting the conventional oil peak with expensive shale oil and tar sands failed.”

Like most analysts, including Birol at the IEA, Mushalik expects lower prices will quickly kill off investment in higher-cost, unconventional oil production around the world, especially US shale oil, which is widely regarded as the Saudis’ main objective. Supply will fall, so oil prices will go up again. How quickly is anyone’s guess and depends on whether the price fall drives economic growth, in turn pushing oil demand higher.

“I don’t think that anyone has a model to know which time lag there is between oil price and demand going up because there may be other reasons why demand is down, not just because of the oil price,” said Mushalik, pointing, for example, to economic slowdown in Europe and China.

Mushalik describes it as a “catch-22”: the world economy chokes on high-priced unconventional oil, but when oil prices fall, and the economy starts to pick up again, “then again the oil price is too low to finance all the investment to stop geological decline,” which refers to a decline in the amount of oil left in the ground.

“So yes, some people say ‘oh, the oil price will find its own level between these two extremes — very high oil prices and very low oil prices’, but I don’t think that anyone has a model.” So long as economic growth is dependent on fossil fuels, we will suffer the gyrations of an increasingly volatile oil market, with ramifications for both private investors and governments trying to balance their budgets.

Part of the problem is what oil industry whistleblower Chris Cook, a former director of the International Petroleum Exchange and research fellow of the University College, London, calls the financialisation of the oil markets, in which prices are no longer driven simply by supply and demand fundamentals and are not necessarily a reflection of the scarcity value of oil. Cook claims to be one of the very few who correctly predicted the oil price crash, as he wrote in the Asia Times just before Christmas:

“I was honored in November 2011 to be a plenary speaker at a conference convened in Tehran by the Institute for International Energy Studies. I outlined — to a politely disbelieving audience — precisely how the global oil market was being financially manipulated and by whom. Moreover, I forecast then, and many times subsequently, that the oil market price would inevitably collapse to, and probably temporarily through, a price level of $60 per barrel.”

In this 2012 piece Cook tipped the oil price would crash to US$75 a barrel as the Federal Reserve unwound its money-printing program, called quantitative easing (QE) — it took a little longer to unwind than he expected.

The biggest driver? In what may be a conspiracy theory, Cook argues the Saudis have worked with investment banks to monetise their reserves early, selling large quantities of oil using “prepay” contracts — not equity, not debt, not a forward sale or futures contract, but more like a gift card — to risk-averse managed funds (he calls them “muppet” funds) looking for a hedge against inflation (see this piece, which has an interesting comment thread). Cook says the all-powerful Saudi oil minister Ali al-Naimi let the cat out of the bag in an interview before Christmas with the Middle-East Economic Survey (MEES), which was reported around the world, particularly that the Saudis would not cut production even if prices hit US$20 a barrel — even if it meant the kingdom was losing money at that level.

Al-Naimi told the interviewer: “A deficit will occur. But what resources do you have in the country? We have no debt. We can go to the banks. They are full. We can go and borrow money, and keep our reserves. Or we can use some of our reserves.”

The upshot? Cook argues there is a strong correlation between QE and oil prices, charted below, and there is now a window of opportunity to restore some fundamentals to oil markets:

Whether you buy Cook’s theory or not, the intertwining of the financial and commodities markets and the tide of easy money going out has led some, including renowned economist Satyajit Das, to predict there will now be a shake-out of “sub-prime oil” companies with many comparing the high-cost, highly geared, fast-declining shale oil plays in the US to a Ponzi scheme. Debt markets are already pricing a strong chance the most fragile shale oil players will default on their borrowings, through trade in credit default swaps. As Satyajit Das told the ABC’s 7.30 program at the end of last year, there is a lot of uncertainty about the sustainability of the US shale oil boom: “We don’t know how big these reserves are, how quickly they deplete and we know that there is a bubble in that because a lot of money has been borrowed to invest in these.”

Harking back to the sub-prime crisis is highly emotive, but it seems clear that the sudden oil price collapse is driven by more complex factors than a new bounty of unconventional oil supply. In its World Energy Outlook, released in November, the IEA predicted oil demand would rise by 14 million barrels a day by 2040, from roughly 90 million barrels a day now. With North American unconventional production petering out from the 2020s, the IEA said meeting the extra demand by lifting production above 100 million barrels a day will be a huge challenge, falling on the shoulders of a very few countries. The peak oil debate is not actually going away.

In a September piece entitled “Why Peak-Oil Predictions Haven’t Come True”, The Wall Street Journal leaned towards the same conclusion: even if there remains plenty of oil in the ground, a lot of it will stay there because the cost of getting to it — even where it is technologically feasible — is just too high. “There has to be a finite limit” one oil and gas consultant told the Journal: “We face technical and economic limits more than anything else.”

Those technical and economic limits may be more stretchy than geological limits, but they are very real nonetheless. Lots of oil will be left in the ground. The Saudis are the lowest-cost producer — al-Naimi told MEES production costs were as low as US$4-5 a barrel — but there have long been fears their official reserve figures are way overstated.

“How much we can trust in what the Saudis are saying is another matter altogether,” said Mushalik. “We are all basically in the dark.”

“My personal opinion is that Saudi Arabia — and the statistics show that — has not increased production and has not contributed to the glut or the perceived glut in the global oil market. [In] 2014 Saudi Arabia produced just 200,000 barrels a day more than in 2005. In fact I think they are struggling on that level. They won’t exceed it.”

“Peak oil” may well lead to a crisis for the drilling industry, but it need not be of any concern to the motorist. After all, transport fuels can be made from any reduced carbon, such as coal, tar sands, oil shale and so on.

It takes time and money for a fuel refinery to convert from one source to another, so headlines declaring “oil crisis” foretell a temporary period of higher prices at the pump while refineries recapitalise and retool.

Who knows, come the day that energy must come from non-carbon sources, the carbon-based fuels coming from the refineries might well have been sourced from biomass or atmospheric CO2, and the energy from elsewhere.

The problem with the peak oil argument is that the amount of hydrocarbons in the planet is assumed to be fixed. There is now, however, quite a lot of evidence to suggest that this assumption is incorrect.

Just as some scientists now believe there is much more fresh water inside the planet than is contained in the oceans, in time science will change its beliefs about the quantity (and roles) of hydrocarbons in the planetary ecosystem.

I’m not quite certain what the units on the left of the graph are. 78,000 kb/day seems to me to be 78 million barrels per day, which sounds too high, compared to consumption of around 90 million barrels per day.

Last year, America had a very good year in producing oil domestically, recovering 8 million barrels of oil per day. According to the graph, the incremental increase was around 5,000 kb/day (unless they’re using the comma as a decimal point).

I’m guessing that the graph is just referring to total recovery of conventional oil, and not the increase over a baseline (whenever that was).

There’s plenty of oil around. It’s just that recovering a lot of it isn’t economical. And even if it were, the infrastructure required (in drilling rigs, pipes, etc) are expensive and not readily available so even if oil recovery can be increased, it may not be able to meet demand, as the global population increases by 2 billion by 2050, and countries such as India and China develop to reach our standard of living (read, our profligate use of energy).

After a little more reading, I sort of understand. Incremental increase is over a baseline minimum for a given country. Venezuela had a strike in one year, so that is its baseline. If a country runs out of oil in 2014, then that is its baseline minimum. And it would show a positive incremental increase for all the other years. Sounds rather silly to me.

Chris, of course the amount of hydrocarbons on the planet is fixed, even if we don’t know the exact amount. The point is, how expensive will it be to get at it? (EROEI)