If we don’t count its appetite for money and waste, the real problem with the Abbott government’s proposed metadata retention legislation is its infinite hunger for us. The overpriced warrant will permit police and government agencies to feast on the lives of everyday Australians not currently suspected of crime. It’s an order off-the-menu with a blank cheque. This “data about data” will mean almost whatever it wants in future, and the claim that our individual browsing histories will not be consumed by government agencies seems increasingly unlikely. The pseudo-category will be necessarily redefined as our use of online changes; it’s a legislative magic pudding. Metadata is what I say it is. A bit like the “child pornography” Tony Abbott yesterday claimed would be stopped by its retention.

As Bernard Keane explained in Crikey, the Prime Minister’s claims that child-sex criminals can be caught online before they offend is bunkum. At an event with Hetty Johnston, the Helen Lovejoy to Bill Henson’s Marge Simpson, Tony Abbott said that data retention was “absolutely critical” in the fight against abuse. Concerns about the predictive abilities of big data in its sci-fi fight against crime that has not yet occurred aside, the proposed data retention scheme cannot shine a light on the darkness of child pornography. Just as terrorist activity is encrypted and barely enacted on the world wide web, abusive and pornographic materials that represent children are hidden in Tor, VPNs and recesses invented to accommodate it.

Hyper-criminalising all Australians in the lavish Minority Report style does not prevent abuse. It’s a measure that anyone with the merest understanding of telecommunications knows is little more than a costly posture. What it can do generally, and what existing Commonwealth and state law on online child pornography and child-abuse materials have done particularly, is turn some unlikely people into offenders.

Almost needless to say, those Australian who aid in the profit of materials that exploit and abuse children must face consequences. But child pornography and child-abuse material — two legal distinction made in Commonwealth law but not in some state laws — are, like metadata, extendable definitions. The 2008 case of a New South Wales man who was found to have lewd images of children depicted in The Simpsons on his computer was convicted with possessing child pornography. In 2009, a Queensland man was charged with distribution of child-abuse materials, which are interchangeable with child pornography materials under Queensland law, for sharing a video of a circus family that had already been classified with an MA15+ rating. Cases that criminalise teens for “sexting” arise, although these have prompted some remedial legislation in Victoria, and fandom communities whose writing depicts characters just as fictional as The Simpsons in carnal acts has found itself not to be exempt from the extendable definitions of “child pornography”.

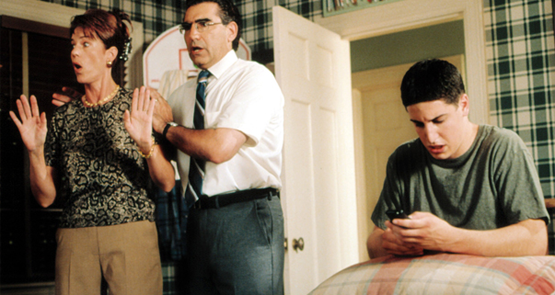

Some of the legislation — genuinely, if poorly, designed to protect people under the age of 18 from exploitation — can criminalise the very young people who produce as well as consume this stuff. The production and consumption of Yaoi, the fan fiction written by young women describing young men in sex acts, are illegal acts in Australia and, in fact, possession of a film like American Pie, which depicts characters possibly under the age of 18 in consensual sex acts could, at a pinch, find you in a lower court.

A defence of depictions of “weird” sex or tawdry communications by teens or Queensland grandfathers who share internet “fails” might seem like an odd use of one’s time and passions. But bad or questionable tastes cannot be criminalised and left to prosecutorial discretion. Our recent legal past has shown that materials not very far removed from the sort of palaver one sees on Australia’s Funniest Home Videos can transform a life.

Those of us who insist that metadata retention is of no concern to them might want to consider that they have already committed what could be interpreted as crimes. To “shine a light”, as Abbott has insisted he will, on the dimmer recesses of our desire, rather than on genuine criminals, is not only a waste of our tax dollar, it’s a diminution of the self.

I have read that NSA classifies all Tor users as extremists – regardless of their reason for use.

The era of the thought police has arrived, watch what you think about, be careful what you dream at night, you are being watched.

Ahh there’s that Queensland Police again, a few years before spying on its own cadets.

Yes, an important issue here is the metadata definition residing in the regulation – more easily changed – than the act.

Then we have today’s added irony that Bernard pointed-out: “blowing half a billion dollars on information-gathering is apparently reason enough to dump a census — but not reason enough to dump a data retention policy that will have none of the benefits a census would deliver.”

Oh oh, I need to slip-in a Abbott-as-Jesuit “nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition” bit.

Pleased to see someone finally calling out the breathtakingly self-righteous Ms Johnston.