This week nine business rent-seeker and lobby groups issued a statement attacking both the Coalition and Labor for reform timidity, comparing them to the “reform giants” of the Hawke, Keating and Howard years and, inevitably, finding them wanting:

“Our high standard of living compared with most other countries is due largely to generations of courageous business and political leaders, supported by a hard-working community, who have championed difficult but necessary reforms to improve productivity and create wealth.”

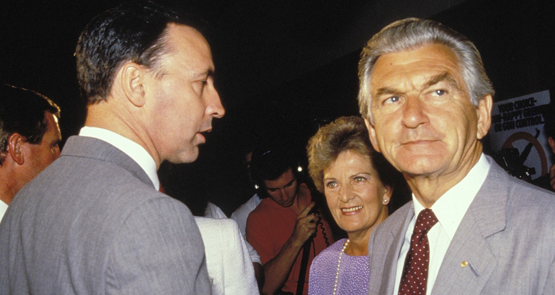

It’s a common enough lament, including from most of the media — current politicians are no match for the remarkable combination of Hawke and Keating in selling big reform; they lack Peter Costello’s fiscal rigour, they can’t hold a candle to John Howard’s political bravery. In short, they don’t lead — not now that the Abbott government has accelerated to the lazy, do-nothing stage that most governments eventually reach, inside its first 18 months.

It’s interesting to fact-check and tease apart this narrative. It continues an idea first put forward by Tony Shepherd when he headed the Business Council, that the only worthwhile reforming politicians are, in effect, policy kamikazes who are willing to accept defeat rather than avoid reform. “Past giants of economic reform did what was right for the long-term benefit of Australia and not because it was politically expedient,” the statement says. It’s the sort of otherworldly view of politics that you often hear from the hard Left — that it’s better to be true to your beliefs than compromise them as part of the shabby deal-making of politics. And it’s nonsensical anyway: you can’t reform from opposition, and if you lose power to political opportunists, your reform efforts end up being reversed — look at what the Abbott government has done to the carbon price, hospital funding and the Gonski education funding reforms — all key reform achievements of the Gillard government.

What’s more amusing is the line about “courageous business leaders”. Every MP who has served in Parliament since the 1980s would be justified in laughing at that one, as if people who have never bothered to throw their hats into the political ring and step up for public life can put themselves on the same podium as politicians who have subjected themselves to voters. How much courage does it take to whinge in chairman’s lounge about politicians, to opine in the columns of The Australian or The Australian Financial Review, to issue press releases condemning things, to lecture the rest of the community about how lazy they are, from the safety of an income that most people can only dream about?

More to the point, it’s wrong. Who opposed tax reform in the Hawke years? The Business Council. Who opposed compulsory superannuation? Employer groups and the Coalition. Who bitterly fought fringe benefits tax and tried to use it in a campaign to throw out the Hawke government? The entire, long-lunching business community. Who savagely opposed the petroleum rent resource tax? The mining industry. As often as not, the key reforms of the last 30 years have been fought by business groups, not welcomed, because it threatened their interests in maintaining the sheltered, lazy economy they prospered in.

And as Scott Morrison correctly pointed out, when it comes to supporting specific reform policies, business goes strangely silent. Nor has Morrison seen the worst of it. When Labor was copping a hammering from News Corp and the Coalition over its cuts to welfare payments (“class warfare”!), where was the Business Council or the rest of the usual suspects to lend support to the then-government in trying to achieve fiscal discipline? Where was the business sector’s support for the long-sought company tax cut Labor wanted to give them, funded by the mining tax? Only the superannuation sector spoke up for that. The rest? Silent as a political grave.

“There’s a reason Australian voters are resistant to this new type of “reform” — it’s because they won’t benefit from it, and never will.”

All of this is just the usual hypocrisy and deception of the business lobby, sure. But it’s hard to avoid the sense that there is something bigger at work here, that it isn’t all political ineptitude and cack-handedness from politicians, or selfishness and resistance to reform from voters. For a start, voters have never been enthusiastic about reform; Howard, who was partly elected because of a sense of “reform fatigue” with Paul Keating in 1996, actually lost the popular vote in 1998 following his GST campaign; even when they enjoyed the unprecedented prosperity of the pre-GFC mining boom, voters felt aggrieved about inflation and interest rates and kicked Howard out in 2007.

And are current politicians all that bad? Julia Gillard shepherded through the Gonski school funding reforms in the face of trenchant opposition from the Coalition and reluctance from the states, using good process and skilful politics. She twice raised income taxes — once temporarily for a flood levy, then permanently to fund the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Wayne Swan achieved the unprecedented feat of preventing a mining boom from causing an inflation blow-out, quite apart from the Rudd government’s efforts at preventing a GFC-induced recession that would have inflicted misery on hundreds of thousands of Australians and potentially undermined a fragile financial sector. For all his hypocrisy and “class war” bullshit, even Joe Hockey stepped up and sought to make serious inroads into the growth in family tax benefit spending and pensions growth, as well as finally saying no to the automotive sector.

Maybe there is now an ever-widening gap between what the reform lobby demands and what voters are prepared to tolerate. But it’s not because voters are grown more insular or more reform resistant, it’s because of what kind of reform is demanded by the likes of the groups that signed onto this week’s missive.

Voter resistance to reform has, judging by polling, tended to be driven by the belief that the community won’t benefit from reforms, but the private sector will (a key reason why privatisation is still so strongly opposed by all voters). The problem is, most of the reform agenda now being pushed by big business has limited or no community benefit, and is primarily aimed at increasing corporate profits.

Thus, labour market deregulation, including the current campaign against penalty rates, is a key element of the business reform agenda, despite compelling evidence that it won’t benefit the community: Workchoices cut labour productivity, while under the Fair Work Act it has increased significantly; industrial disputes remain at historic lows; far from causing wages blowouts, the FWA has seen wage growth flat or negative; the sector allegedly choking on penalty rates, cafes and restaurants, in fact is one of the biggest and fastest growing employers in the country. Nor does allowing business to use the migration system to temporarily import staff (or, more likely, “independent contractors”) to replace higher-paid Australians benefit Australia.

The other holy grail of reform, lower company tax rates — also backed by Treasury, it’s not just on the business wishlist — is supposed to deliver economic growth benefits but creates a fiscal hole that can only be filled by heavier taxation on individuals, while undermining taxpayer confidence in the fairness of taxation, a crucial ingredient in a functioning fiscal system.

The corporate desire for lower taxes also contrasts with regular calls for greater fiscal discipline and a return to surplus — business wants to pay less tax and see budget deficits reduced more quickly at the same time. The logical solution is smaller government, despite the relative low overall tax burden that Australians bear compared to other developed countries.

In short, the core “reform agenda” pushed by business groups isn’t a continuation of the sort of 1980s/1990s-style agenda but American-style neoliberalism, in which workers have fewer rights in a globalised marketplace and are paid less and companies and the wealthy pay little tax and face little regulation.

The result is two “reform” agendas: one that builds on the last 30 years to deliver long-term increases in competition, productivity and economic growth — a better educated workforce, a more efficient health sector, greater participation, strengthening our capacity to innovate, more competitive markets — and the one increasingly preferred by business, which aims for the sort of US corporate model that even John Howard eschewed, that leads to massive inequality, an underclass of working poor, a shrinking middle class, unconstrained business and minimal government.

The latter sort of reform isn’t on the same continuum as most of that of the last 30 years, especially that undertaken by the Hawke, Keating, Rudd and Gillard governments, which focused on the national interest, not the business interest, and accepted Australian workers as an integral part of reform, not an afterthought or intentional target; nor is it even especially contiguous with much of the Howard agenda, in which losers from reforms like the GST were compensated and key markets like the financial sector were subjected to specific and effective regulatory frameworks, rather than allowed to run rampant as US and European financial institutions were allowed to before the GFC.

There’s a reason Australian voters are resistant to this new type of “reform” — it’s because they won’t benefit from it, and never will. Their natural scepticism about the benefits of economic reform in this case serves them well: this is not about the national interest, but about business interests.

This is just a regurgitation of previous Crikey articles which led to comments that were ignored by the Crikey Collective; but who’d be surprised by this?

Well said, Bernard. Why don’t we ever see these facts published in the MSM?

Oh! that’s right. The media in this country is part of the ‘business reform group’.

Surprise, surprise!!

Go Norman, you are always good for a sly chuckle.

Meanwhile the longer this longer this dangerous and icompetent mob blunder about, the better all previous federal pollies look..!!

“Reform” is a very over used word – by politicians, the “media”, and business. A good article looking honestly at who benefited from past “reform”. Is it any wonder hackles rise amongst voters when they hear the word. In SA we are presently benefiting from health reform : hospitals closing, staff sacked, and money monumentally wasted. We have already benefited from the reform of our energy sector: higher prices and poorer service. Now there are proposals to reform our housing sector: high rise living for everyone with planting on external walls to reduce heat arising from so many trees and green spaces having been removed by developers to build the high rise.

Yes, well said Bernard.The program of reform for the Abbott government is a program to make members of the BCA and CMI richer. It is also driven by the ideology of the Treasury.

When markets are complete, perfectly competitive and there are no externalities, it is paradise: such a market economy can do at least as well as any alternative system for consumer welfare; and it can be as efficient as any other arrangement. That no market economy, especially including Australia’s, can be like this is no problem for Treasury, as they think, unlike any scientist, that they can simply assert that our economy works as if it is like the economy to be found in market paradise. “Evidence” based policy is then said to be policy based on what this mumbo jumbo says will be the outcome of applying any policy. Treasury officials will unsuspecting politicians like Hockey, who have an invisible understanding of economics, that a tax on petrol is fine because the poor will pay less because they have fewer cars. They will tell Hockey that cutting taxes will raise growth in the economy because it ill encourage workers to work more and firms to invest more. The media, with exceptions like Bernard, will tell the same story as Treasury. No wonder the public does not trust plans for so-called “reform.”