Food can be a damn serious business. We all know what happens if you have none, and that shortage is a reality that about one in nine people on this planet have to deal with.

But in communities where supply is plentiful, food can become many different things and have a variety of meanings imposed upon it that extend well beyond sustenance, flavour, and even beyond the origins of the ingredients.

The meanings and narratives we draw from food (and you can be sure, food now has narratives and “tells a story”) have been integral to the rise of food porn and the fetishisation of haute cuisine and its masters.

To my mind, the best chefs in the world have a sense of playfulness and understand that the sensory experiences of food can be evocative, thrilling and entertaining. Do they change the world? No, but they can capture tastebuds and imaginations, inspiring and exciting their customers.

But there are those out there who treat food as a matter of life and death in social and economic circumstances where that couldn’t be further from the truth, elevating what they eat to some kind of text capable of enlightenment. It’s probably best to just treat your cauliflower foam as a novelty, rather than asking it what it has to say about humankind.

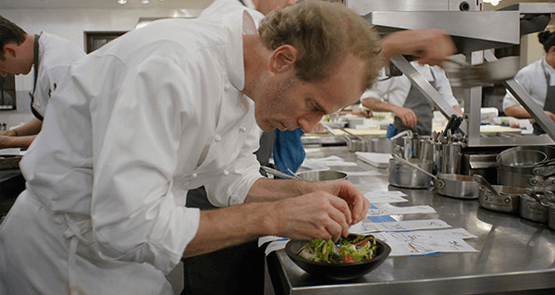

Netflix has officially entered the food porn game with a glossy new six-part documentary series Chef’s Table, which premiered over the weekend. Produced by David Gelb, the series profiles six leading chefs and the various events in their lives that have shaped their philosophies towards food.

The food looks consistently stunning — you’ve never seen dishes that so consistently cross the line into visual art on TV — and the writing is genuinely strong. Or at least it tells stories with more clarity than the food could.

Of course, one of the biggest problems the series faces is that there are really only a handful of celebrity chef narratives, and most of them go like this: a tortured genius who trained hard in classic culinary arts uses that basic technique to break out and carve his (and it is nearly always his) own voice.

The conflict comes from the establishment, which is, at first, outraged by the young upstart’s disrespect for the cuisine. Nobody comes to their restaurant at first, but eventually the chef is given the recognition they deserve. Heard that one before?

It’s a tale that’s particularly well-told in several episodes of Chef’s Table, especially the premiere featuring Italian chef Massimo Bottura, who has spent his life experimenting with the cuisine of Modena, much to the initial disgust of the local foodies.

Melbourne’s Ben Shewry gets his own episode, which is charming for his modesty, even if the constant down-playing of his achievements doesn’t sit all that comfortably with the high-drama of the series.

Another episode, featuring Japanese-American chef Niki Nakayama, is particularly intriguing because it explores how a female broke through in the very male world of Japanese cuisine.

Nakayama identifies that her food is capable of embodying personality traits and being things — outlandish, loud, bold — that she’s personally not comfortable being, due to her cultural background.

But the second episode in the series, which follows New York chef Dan Barber, is cringe-worthy in its over-earnestness and in its desperation to draw meaning out of every morsel.

Barber actually characterises America’s continual supply of good produce as a “great tragedy” of US history because it’s meant that American cuisine has never had to adapt to using difficult ingredients and develop a distinctive voice. Yes, that’s right. The lack of any obliterating famines is a “great tragedy” of US history.

Barber’s New York restaurant, Blue Hill, is focused on the agricultural side of fine dining and aims to use the best produce available in the truest manner possible. Every second sentence he utters is about the purpose of his food, the “deeper questions” and the raison d’etre for his restaurant.

“The fascination of eating at Blue Hill is that everything that comes out there, you can look so deeply into,” says one of his ardent followers.

Barber’s breakthrough moment? When he over-ordered asparagus and decided to use asparagus in every single dish that night (including asparagus ice cream).

“I was just like, you know, we’re going to freaking embarrass ourselves tonight,” Barber says. “But I was so dug into my damn position there was no way I was going back on it. I felt like this was a test I couldn’t afford to fail.”

Who happened to show up that evening? Leading food critic Jonathan Gold, of course. And lo, and behold, he loved the asparagus.

Barber also wants his diners to think not just about what they’re eating but about what they’re eating is eating. So he feeds his chickens red peppers so they have red yolks. Ground. Breaking.

Barber says of his cooking: “It’s not just about the dish. It’s about what the radish represents. It has to add up to something much larger than a plate of food.”

Does it, though? When did we become so desperate for the food that we consume to really mean something? We’ve long understood that porn doesn’t need a narrative to fulfil its purpose, so why is a pure sensory experience no longer enough for food?

The bizarre thing about watching Barber’s episode is how often he and his followers talk about change, and a movement, and a philosophy, but never articulate one with any clarity.

For a series which is full of sensory riches and some fine personal stories, this particular episode is an endlessly frustrating, “serious” hour of television, which never manages to make a coherent point and trips over a fine line into fetishisation in its quest for meaning.

There’s at least one lesson Netflix could learn from porn: nobody’s watching for the story.

*This article was originally published at Daily Review.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.