Peter Bouckaert (center) meets with Colonel Saleh Zabadani (far left) and General Mahamat Bahar (second from the left) of the Seleka forces in Bossangoa

Hunting down African warlords in remote bushland to tell them you’ve documented a murder they committed an hour before is probably not part of your job description.

But it is for Peter Bouckaert.

And the average rebel commander is “shit-scared” of the International Criminal Court, he says.

Bouckaert is Human Rights Watch’s emergencies director. He’s attended fact-finding missions in many of the world’s conflict hotspots over the past two decades: Lebanon, Kosovo, Chechnya, Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel and the Palestinian Territories, Macedonia, Indonesia, Uganda and Sierra Leone, among others.

More recently, he played a significant role in helping bring the world’s attention to the conflict in the Central African Republic, the closest Africa has come to genocide since 1994, he says, which had been largely ignored by the media.

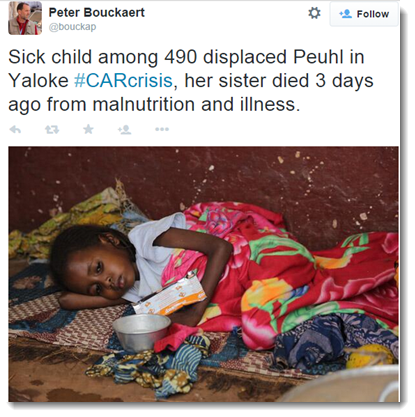

In a speech at Monash University’s Castan Centre for Human Rights last month, Bouckaert told the story of how he tweeted a series of photos of displaced Peuhl people who were surrounded by hostile forces and starving because the government wouldn’t let them escape across the border to Cameroon.

A few hours later, he took a call from the Secretary-General of the United Nations Ban-Ki Moon, and thanks to the pressure brought to bear on the Central African Republic’s government, most of the refugees have since been allowed to flee.

Bouckaert says, oddly, those committing atrocities can be receptive to dialogue — especially when they realise they might end up in the dock at the International Criminal Court.

“It is very important that we try to reach and reason with the people who commit these crimes,” he told Crikey. “It’s not to excuse their conduct, obviously, but they’re the ones who are making the decision to carry out abuses.

“It takes a bit of courage to walk into a room full of people with guns and explain to them that the crimes they’ve committed could lead to them being prosecuted.

“But I tell them, ‘We’re among men here, and I’m not going to tell you some fairytale story and then go to New York or Geneva and tell the International Criminal Court something else. We may be one day sitting across from each other in the court room where I’m testifying against you, so I want to warn you. You should know the consequences of your actions.’”

Many militia leaders are surprised someone has even bothered to make the journey out to the conflict zone.

“When I describe it your initial thought is, ‘why don’t they just kill him?’ But actually I think it earns their respect to be honest and straight with them.

“In my experience when you approach them as human beings and we explain our work, working impartially, focusing on the responsibility of all sides, including working to protect the populations they claim to represent, a lot of them do listen to us very carefully,” he said.

Bouckaert recalled that he once sat down with a militia leader and asked him if there were any child soldiers in his army. There were, came the proud reply — the guerrilla had been a school principal before taking up arms, and of course he’d brought the kids along with him.

Bouckaert explained that this was considered a war crime and that he could be prosecuted by the International Criminal Court. The next day, the rebel leader ran up to Bouckaert to tell him he would stop using child soldiers, telling him “I don’t want to end up in the Hague!” The child soldiers have since been demobilised.

When he’s not chasing rebels through the bush, he spends some of his time in California meeting with companies like YouTube, Google and Facebook, discussing the development of technologies allowing improved collection and verification of documentary evidence from conflict zones.

Human Rights Watch has used satellite pictures to demonstrate the existence and extent of destruction of the ongoing ethnic cleansing campaign against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, as well as the Nigerian army’s burning of the town of Baga, and others.

Until around 15 years ago, satellite imagery was the domain of spy agencies, but the launch of several American and European companies has made it possible to buy imagery of most places in the world.

This has helped HRW evade some of the restrictions governments put on such information. During the final days of the Sri Lankan civil war, there were reports the Sri Lankan government was shelling an area filled with civilians, though the government denied it.

HRW requested the UN Institute for Training and Research’s satellite program (UNOSAT) release imagery of the area, “but when they saw what it showed, basically calling out Sri Lanka as a liar, because the Sri Lankans said there are no more people left in Nivani and said they were not shelling the no-fire zone they had established themselves, UNOSAT decided not to release them.”

Instead, “we decided that we would do it ourselves”, he said. “We now have the best satellite analysis program of anyone in the NGO world.”

And what does he think about Australia? “The one issue that constantly comes up is in terms of burden sharing when it comes to the global refugee crisis the world faces right now. It’s very detrimental to Australia’s image to have this gun-boat policy,” he thinks.

The debate within Australia about its role on the international scene is “narrowly focused”, and too often falls back on issues such as putting “boots on the ground” in Iraq, coming too late for, or ignoring completely, early intervention, mediation and other diplomatic possibilities.

Nonetheless, the new Australian chapter of HRW has been surprised at the level of access it’s gained to the current federal government. He hopes the government will be willing to listen to the organisation’s advice on international issues.

“When we meet with policymakers, we come with a unique perspective from having worked in these countries for many years, understanding the underlying factors that are causing the human rights problem, and very clear and sensible recommendations. We hope to build the same relationship with the Australian government to enrich their knowledge about these crises and to suggest recommendations we think are the most sensible about resolving them,” he said.

When it was suggested the relationship between HRW and the Australian government might encompass both carrots and sticks, he joked: “They’ll feel the stick anyway, I’d rather have them read about the carrot!”

If only the Faux Progressives in Western Democracies would put their efforts into people like him, instead of rabitting on about trivial matters, the Human Rights Campaign could deserve a better image.