The Reserve Bank’s exasperation with the government and politics more generally has boiled over — albeit in the passive, gentle language of a central bank — in yesterday’s speech by governor Glenn Stevens.

The speech is a primer on Australia’s current tepid economic growth and what the sources are for strengthening that growth, and should be required reading for every politician before they open their mouth about the economy, right up to the Treasurer and the Prime Minister.

It looks increasingly unlikely that Joe Hockey will make it through the winter parliamentary recess with his job intact after yet again displaying his capacity to completely wreck the government’s communications strategy. Every time he makes these sort of gaffes, he sucks precious political oxygen from the government’s efforts to send a coherent message to the electorate, with the media cycle sidetracked for several days onto whatever topic Hockey has tripped over. So Scott Morrison should make sure he reads Stevens’ remarks carefully.

As Stevens notes, the economy is not performing as the Reserve Bank has been hoping and forecasting for a couple of years — the expected fall in the mining investment boom (which still has a way to run, he says) has not been replaced by a lift in business investment outside the mining sector, and the dollar remains stronger than the Bank would like. On the upside, we’re building a lot of houses and selling a lot of iron ore, in particular, which contributed strongly to the March-quarter GDP growth figure. Don’t expected the same in the June-quarter figure, Stevens says.

So where can more growth come from? The RBA will contemplate further interest rate cuts, but knows that it’s running out of ammunition and each bullet is getting less effective, anyway, because if businesses won’t invest when rates are as low as they are currently, they won’t invest after another 0.25 percentage point cut.

What about households? They’re already digging into their savings to finance expenditure (the savings ratio fell in the March quarter), because wages growth is so low and overall national income growth is weak.

So if households have limited capacity to spend more, business is refusing to invest despite record low interest rates and monetary policy is running out of puff, that leaves fiscal policy. Except, governments are cutting spending, not increasing it (“and fiscal consolidation still has some way to run”) — although Stevens gives the Abbott government a pat on the back for cutting back on its consolidation. “I think the Government is on the right track in not seeking to compensate for lower revenue growth by cutting spending further in the short run.”

So far, so normal. That analysis isn’t anything especially new. But then Stevens ends with a clear shot, at the government in particular, and the political class generally:

“… it would be confidence-enhancing if there was an agreed story about a long-term pipeline of infrastructure projects, surrounded by appropriate governance on project selection, risk-sharing between public and private sectors at varying stages of production and ownership, and appropriate pricing for use of the finished product. The suppliers would feel it was worth their while to improve their offering if projects were not just one-offs. The financial sector would be attracted to the opportunities for financing and asset ownership. The real economy would benefit from the steady pipeline of construction work — as opposed to a boom and bust. It would also benefit from confidence about improved efficiency of logistics over time resulting from the better infrastructure. Amenity would be improved for millions of ordinary citizens in their daily lives. We could unleash large potential benefits that at present are not available because of congestion in our transportation networks.”

Moreover, this isn’t just about physical infrastructure but about educational and technological infrastructure. The problem?

“The impediments are in our decision-making processes and, it seems, in our inability to find political agreement on how to proceed.”

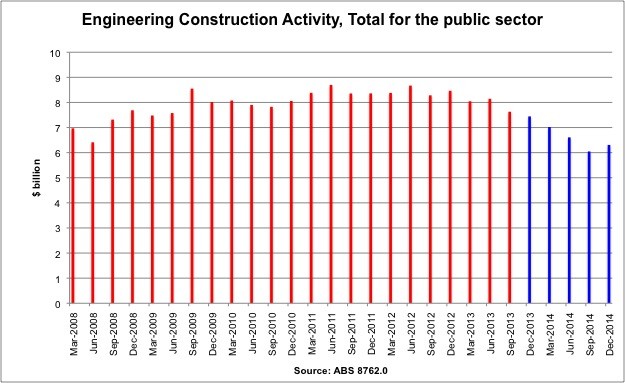

Don’t be under any misapprehension. This is a direct shot at a man who boasted he would be the “infrastructure Prime Minister” but who wasted a year rejigging Infrastructure Australia, whose second budget had minimal infrastructure spending outside a gimmick pot of money for northern Australia, and who has presided over a big fall in infrastructure investment since he came to office.

Stevens makes three key points about infrastructure spending: experience shows it’s poor as a short-term counter-cyclical measure, because it takes too long to ramp up (many of Keating’s “One Nation” infrastructure projects were barely getting going when the early-’90s recession was already over), now is a good time for investment because governments can borrow at very low rates, and a process for having a consistent pipeline of appropriately selected projects is the best approach (hint hint, in contrast to politically motivated and lumpy spending).

It’s as clear a call to arms as you’re going to hear from a central bank about how to do something effective about lifting Australia’s growth rate.

As if in response, Abbott was talking about infrastructure investment this morning in one of his regular, obsequious attendances at an Alan Jones monologue. In response to a rant about wind farms from Jones, Abbott endorsed the entirely fictional claim that wind farms cause health problems (a claim demolished by an inquiry Abbott himself initiated) and actually boasted to Jones of reducing infrastructure investment, the day after the head of the Reserve Bank spoke of the importance of lifting it:

“What we did recently in the Senate was reduce, Alan, reduce, capital R-E-D-U-C-E the number of these things that we are going to get in the future. Now I would frankly have liked to have reduced the number a lot more.”

Abbott and his government are not worried about the performance of the economy, good governance or infrastructure investment — just plain partisanship and a particularly dim-witted, anti-science ideology.

“Abbott and his government are not worried about the performance of the economy, good governance or infrastructure investment — just plain partisanship and a particularly dim-witted, anti-science ideology.”

A line that I hope will spring constantly from every-ones lips as often as possible until an election dismisses these odious clowns! A complete clusterf***k of morons!

But RR, who else in there? If we went to the polls today Shorten will go the way of Milliband. It’s depressing.

As a scientist involved in a small business that has benefited from grant funding from Commercialisation Australia I am appalled every day any of our leaders make such stupid gaffes. With CA funding my own business is now well on the way to bringing innovative solutions to diagnosing a serious disease with greater accuracy and the beneficiaries will be the citizens of this country as well as reductions in the massive costs of treatment and productivity losses.

Could we have done this without CA money? NO.

This country deserves better than Abbott et al. Much better. And of course Commercialisation Australia is now “on hold”. Until when?

I think it was Keating who said words to the effect of God help Australia if Abbott is ever PM. Never was a truer word spoken. When you say Bernard that “Abbott and his government are not worried about the performance of the economy, good governance or infrastructure investment — just plain partisanship and a particularly dim-witted, anti-science ideology” you are saying what I suspect the majority of people in this country believe. Normally one would hope for an early election but in this case the likely result would be Shorten as PM. Evidence that that would be an improvement is notably lacking.

“Abbott and his government are not worried about the performance of the economy, good governance or infrastructure investment — just plain partisanship and a particularly dim-witted, anti-science ideology.”

All very well to notice this now, but why wasn’t the whole press gallery pointing this out prior to the last election when it was obvious to anyone who looked that this was all there was to an Abbott government?