If Australian politics had an out-of-touch-o-meter, a lot of politicians and media pundits think it would’ve gone ding this week. Treasurer Joe Hockey’s dim platitudes on housing affordability, dished out as he publicised the government’s crackdown on foreign investment, added fuel to a debate about government policies incentivising property investment that has been raging for years.

The Greens want to end negative gearing and other tax breaks, and now Labor is seemingly reconsidering its own position on the issue — the significant budget savings are surely an attractive bonus. Way back in 2003, the Reserve Bank (RBA) tendered a submission to a Productivity Commission inquiry on first-home ownership. The executive summary noted: “The ratio of the price of the average home to average income has risen sharply … making it increasingly difficult over recent years for first-home buyers to achieve home ownership.” It sounds pretty familiar, and in the years since the inquiry prices have continued to soar to record levels. But aside from affordability concerns, there is the real threat that the current boom will lead to what most booms eventually lead to: a bust.

Before we look at the risks for Australia, lets examine how housing affordability is generally measured. One of the most commonly used metrics of sustainability in home price growth is the ratio of residential property prices to household income. If the difference between the two becomes great, it can be an indicator that housing is overvalued. A 2012 RBA paper is rather critical of this approach, but it is the standard metric in reports from both the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Another measure compares property prices against rents, because house prices and rental yields are generally expected to track similarly if the property is correctly valued. A wide gap either way can suggest under- or overvaluation. Additionally, there are various housing affordability indexes in use around the world that also take into account external factors such as interest rates and local policy settings. The Housing Industry Association and the Commonwealth Bank jointly publish their own housing affordability index, which attempts to measure the ability of households to meet the cost of buying their first home. They claim housing is actually becoming more affordable, but then perhaps it’s best not to listen to the banks on these things.

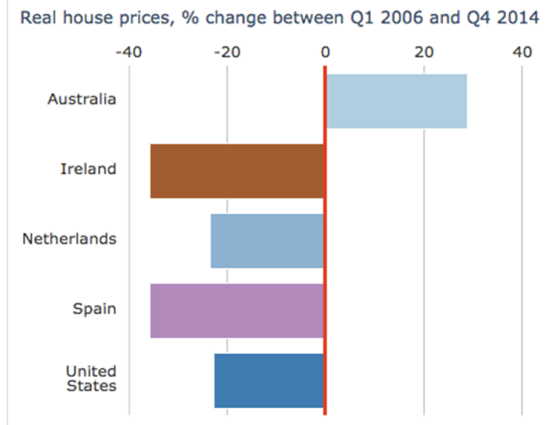

The US, Spain, Ireland and the Netherlands all experienced major housing busts — or market corrections, if you’re an economist — during the last decade. While the GFC affected housing markets in dozens of countries, not all crashed on the same scale. The chart below shows the astonishing housing “corrections” experienced around the world, and the opposite trend in Australia as house prices continued to rise despite small dips in 2007 and 2010.

Source: The Economist (Australian Bureau of Statistics; OECD)

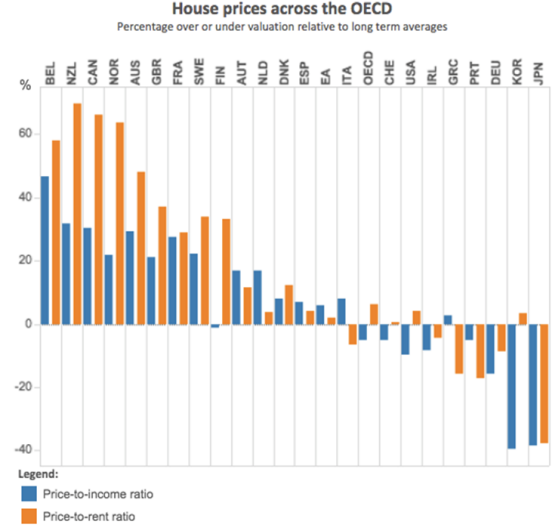

But what does the data tell us about the state of these markets before they crashed? When the GFC hit in 2007, Spain’s housing was overvalued by 67% according to the price-to-income measurement; Ireland’s by 62%; the Netherland’s by 45%; and the US’s by 22%. The US is an outlier in this group, in that its price-to-income ratio was never very high by OECD standards. Greece experienced a massive downturn, though its housing market was not considered strongly overvalued before the GFC hit. Clearly, the story is a not a straightforward one: other countries were in the midst of housing bubbles but managed to avoid catastrophic downturns — Australia, the UK, Canada, and Belgium included.

So where does Australia sit compared to other countries that felt the bubble burst? According to The Economist’s calculations, which use mean income as opposed to median income in its formula, Australia’s housing is currently overvalued by about 38% relative to long-term averages, down from a high of just over 40% in 2010. This is significantly higher the US when the GFC hit, but much lower than the three countries to experience massive downturns. When compared against rents, Australian houses are overvalued by 60%, according to Economist data. Before the crash, Ireland’s housing was rated as overvalued by 125% on this metric; Spain’s 84%; the Netherland’s 50%; and the US’s 39%. Again, Australia appears to be in the danger zone without setting off the alarms. The chart below shows where Australia (fifth column from the left) currently sits in the OECD rankings, which use median income as their indicator.

Source: OECD

The OECD has voiced its concerns about the sustainability of the Australian housing market, grouping it with the UK, Canada, and New Zealand and others as among the “most vulnerable to the risk of a price correction”. The main concern is a sharp rise in the cost of borrowing, which looks unlikely in the near future, or a slowing in the growth of incomes. With wages already stagnant in real terms, a sudden rise in unemployment could mean the whole cart tips over.

If you need some comfort in all this, Assistant Treasurer Josh Frydenberg assures us there is no bubble, and Tony Abbott is less than concerned. Perhaps we should just hang on and enjoy the ride, but an RBA discussion paper released last year affirmed what plenty of people feel: “At current prices, rents, interest rates and so on, the average household is probably financially better off renting than buying.” And that’s the thing: perhaps it’s not the loud crashing of markets we should be worried about hearing, but the tiny, diffuse, sounds of dreams quietly being shelved.

Remove the ads or give me my money back

I’m with Paul

What ads?

From deep inside what is left of my memory I think that there is a study done of house prices in Holland (Amsterdam )going back hundreds of years. They used this as the data was the only data available. This study indicated that rising prices are only sustainable at what we would consider a low number.

Now this is one study and accurate data is hard to find but I think it does say someting.

The other thing that is being missed is that high housing prices are bad for the economy. They require high wages which adversely affects our ability to compete.

It also directs funding away from productive purposes to non-productive because such large loans are required.

Also contrary to the claims negative gearing increases rents not lower them. The reason is obvious. If somebody can’t buy because an investor has bought then they are thrown on to the rental market. More demand which according to the Law of Supply & Demand means higher prices(rents)

Yep, what ads?

Anyway housing is now affordable with Joe’s new initiative:

http://www.getagoodjobthatpaysgoodmoneyinjoehockeysoffice.com.au/

Yes.

It’s been in a bubble for nearly two decades, and unaffordable for closer to three.

Affordable housing runs at a ~3x multiple of income – and that calculation should use individual income, not household income. Do the math.

Expensive housing is a deliberate policy choice. It does not need to exist.