Not six months ago, political pundits were preparing to draft obituaries for yet another short-lived Australian prime ministership.

It’s a measure of how surprising the course of events has been since then that only the most cockeyed of conservative partisans can say they saw it coming.

Almost from the moment the Liberal leadership spill motion of February 9 was out of the way, Tony Abbott’s personal approval ratings began a sharp upward trajectory that is only now beginning to taper off.

Such were the depths of the starting point that Abbott’s approval ratings remain at least 10% south of his disapproval. But, in the context of a two-horse race, the more important point is that he has now drawn level with Opposition Leader Bill Shorten, who is roughly 10% down on the respectable ratings he was polling throughout last year.

It doesn’t take a dedicated Abbott-hater to be at least a little puzzled by the extent of the improvement, which has gone well beyond what might have been expected from a natural correction.

Some help in drilling down into the attitudes behind the shift is provided by Essential Research, which has conducted detailed polling on leaders’ attributes on a semi-regular basis since 2008.

This was most recently done a fortnight ago, and it produced the finding that Abbott’s greatest strengths were intelligence and capacity for hard work — qualities that were respectively attributed to him by 59% and 51% of all respondents. While clear majorities continued to rate him as erratic (54%) and out of touch with ordinary people (65%), these were much improved from the previous result in February, when the respective figures were 60% and 72%.

However, a closer look at Essential’s results over the last seven years suggests that such numbers are not as illuminating as they may at first appear.

On top of the improvements just noted, the latest figures suggest voters have also come to see Abbott as more capable, trustworthy and visionary, and in possession of a better understanding of the problems facing Australia. Had the question been asked, they would no doubt also have found that he had become better looking, all visual evidence to the contrary.

Put simply, any specific attitude concerning a leader is heavily influenced by a more general perception of him or her as good, bad or indifferent, so that responses to Essential Research’s suite of questions have a strong tendency to all move in the same direction.

Furthermore, any given set of numbers that might emerge will say almost as much about perceptions of politicians in general, as the specific leader in question. Whatever else voters may think of their leaders, they are generally happy to allow that they wouldn’t have risen so high in their chosen vocation if they hadn’t at least been hard-working and intelligent, while being a lot more reluctant to credit them with honesty and trustworthiness. As such, the aforementioned numbers for Abbott may not tell us much worth knowing, in and of themselves.

To place the results in context, it is necessary to set them against an objective benchmark, which I have done by measuring relationships between leaders’ approval ratings and their attribute measures recorded by Essential.

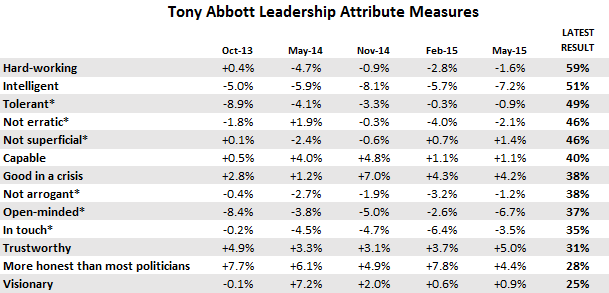

The table below records how Abbott’s results in the five Essential leader-attribute polls conducted during his prime ministership have differed from what might ordinarily be expected of a leader with his approval rating at the relevant time, together with the raw numbers from the latest poll in the right-hand column. For the sake of consistency, negative attributes such as “intolerant”, “erratic” and “superficial” have been inverted into positive ones, and indicated with asterisks.

It should be emphasised that these are relative rather than absolute measures, and do not record the general hardening of attitudes towards Abbott after the budget and the Prince Philip knighthood, or the recovery he has recorded since. What they offer is insight into the changing perceptions that drove Abbott’s ratings down after the 2014 budget, up in the latter half of last year (as recorded by the November result, albeit that Abbott’s ratings were again declining by that point), back to Earth with a thud after Australia Day, and solidly upwards thereafter.

Two attitudes that seem to have been consistent from the beginning relate to intelligence and honesty. Rhodes Scholar or no, it doesn’t seem that voters have ever been persuaded that Abbott is greatly endowed with the former quality, at least by the standards of the top rank of political leadership.

However, his rating on “more honest than most politicians” — although seemingly very weak in absolute terms — has consistently been higher than his approval rating would lead you to expect. Presumably, this is a dividend from the clarity of his ideological positioning, which is consistent with the fact it held up relatively well after the Prince Philip knighthood.

Even last year’s budget didn’t cause particular harm to Abbott’s honesty rating, the biggest shifts at that time being for “out of touch with ordinary people” and, less intuitively, “hard-working”.

The aftermath of MH17, and perhaps also his subsequent success in keeping terrorism at the forefront of the media agenda, appeared to strengthen the perception of Abbott as being “good in a crisis”, which has at least partly stuck with him since.

The changes between the February poll and that of a fortnight ago have been relatively modest, but it’s notable that the biggest shift in Abbott’s favour was for “out of touch”, which had taken a further hit after Australia Day to compound the one it suffered after last year’s budget. This suggests that the more recent budget succeeded in improving Abbott’s image exactly where he needed it most.

As for Bill Shorten, his rating on the “out of touch” question has consistently been highly favourable. However, his other strengths — high scores for being open-minded and tolerant, and correspondingly low ones for aggression and arrogance — are perhaps suggestive of too much of a good thing.

Clearly Shorten needs to find a way to project more killer instinct to persuade voters that he constitutes a viable alternative to Abbott, and to do so in a way that doesn’t evoke uncomfortable memories of his role in deposing consecutive Labor prime ministers.

Labor needs to get a viable alternative PM to lead it?