There has been a solidifying view among Canberra watchers of late that the Prime Minister is, at the very least, carefully considering holding an election well ahead of its natural time around September next year.

Doing so would place him in good historical company. The Menzies, Whitlam, Fraser and Hawke governments were all back at the polls within two years of coming to power, seeking in one way or another to capitalise on the opposing party’s unsettled state post-defeat, and the natural reluctance of voters to cast too harsh a judgement on a government newly established in office.

All four governments were returned, and all but Whitlam’s went on to enjoy respectable-or-better tenures in office.

John Howard’s first term as prime minister was more conventional in its duration, but here, too, the election fell five months ahead of the third of anniversary of his coming to power.

The closest a post-war government has come to serving out a full first term was the Rudd-Gillard government of 2007-10, hardly an auspicious precedent.

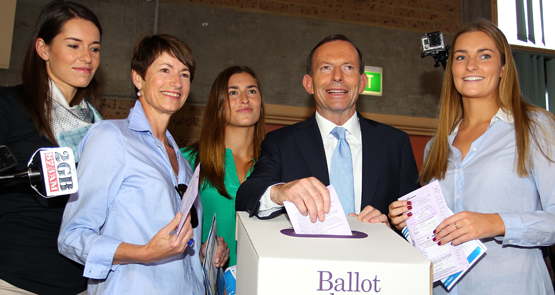

So even before taking into account the specific circumstances that confront him, it would be surprising if Tony Abbott weren’t contemplating an early poll. But as he casts his eye down the calendar for a Saturday that might best suit his purposes, he could not fail to feel great trepidation about the options available, each of which carries very serious drawbacks.

Strange as it may seem, the government’s shaky standing in the polls is the least of his problems. Abbott is reportedly of the view that he can do two points better at an election than whatever the polls might be saying, although it’s not clear if he attributes this to the advantages of incumbency or the deftness of his own political touch.

According to the poll aggregate featured on my blog The Poll Bludger, that leaves Abbott’s underlying position just south of parity with Labor, at least so far as his own assessment of it is concerned.

As it happens, that would probably be enough to get him over the line, since Labor would face newly established Coalition members in nearly all the decisive marginal seats, who are notoriously difficult to dislodge.

However, conventional wisdom says there are no guarantees Abbott will be as well placed after next year’s budget — which, taking into account the ongoing deterioration of the fiscal position, will need a strong smell of austerity about it if the government is to make any boast of its superior economic management credentials.

Clearly then, the suspect has a motive — but is there also the opportunity?

In any other year, prognosticators would be looking to the school term and public holiday schedule and putting red circles around the last three Saturdays in October, which, along with March and December, has always been one of the three favoured months for election timing.

But Abbott faces a difficulty that wasn’t known to his predecessors: the unviability of staging a double dissolution without reforming the Senate electoral system, and the technical obstacles facing such reform.

In seeking to excuse his government’s failure to deliver the budget surpluses that were said to have been in his party’s DNA, Abbott will have to run hard on the problems he has faced with Senate obstruction.

That will ring very hollow indeed if his proposed solution is an election for the whole Senate under the current rules, in which the quota for election would be slashed from its usual 14.3% to 7.7% — making it all but certain that at least one micro-party senator would be elected from each state, barring a radical change in voting patterns since 2013.

Consequently, his natural plan of attack would be to hold off legislating for reform so as to avoid antagonising the micro-party crossbenchers any sooner than necessary, before making the introduction of a bill the canary-in-the-coalmine of a looming election.

The problem with this is that there’s a lot more to creating a new Senate voting system than simply passing the bill.

As it stands, a Senate election count involves hundreds of phases, through which preferences are transferred in myriad directions at changing values as candidates are progressively elected and excluded.

As it could hardly fail to be, this process is computerised — using software the AEC contentiously keeps under wraps, having knocked back freedom of information requests to divulge the source code.

The challenges involved in programming were demonstrated when similar software developed to count the Australian Capital Territory’s Hare-Clark elections was shown by experts at the Australian National University to contain at least three bugs.

So the government should hardly have been surprised to learn that altering the software to deal with new rules would be the work of several months, as Australian Electoral Commission officials explained to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters yesterday.

The only way around the problem would be to entirely replace the single transferable vote system with something much simpler, which would be at odds with modern Australian practice at both federal and state level.

It would also involve jettisoning the cross-party recommendations of JSCEM, making it a very difficult sell in the Senate.

All of which makes it a lot more viable for Abbott to hold off until early next year. Doing so would also allow time to resolve redistributions in New South Wales and Western Australia, without which there would need to be mini-redistributions — an extremely messy contingency that was discussed here last month.

However, an early 2016 poll raises issues of its own, quite apart from the fact that Abbott might well prefer to strike sooner.

After a double dissolution, the start of the Senate term is backdated to the most recent mid-year point. Whenever one might be called, that would mean the middle of 2015 — around about now, in other words.

According to the normal Senate timetable, the last possible date for the subsequent half-Senate election would be May 2018.

Barring a second double dissolution, or the nightmare scenario of House and half-Senate elections held at separate times, an election held early next year would limit the term of government that followed to barely more than two years.

If Abbott is still around in 2018 to face his third election campaign in less than five years, he would have a very hard time persuading election-weary voters that he had delivered the stability and certainty that had been his key selling point in 2013.

Just wondering if Abbott’s morally bankrupt enough to call an election for the period when Shorten’s appearing before the Royal Commission? Actually, that probably should be, would Abbott believe that he could get away with calling an election to coincide with Shorten’s Royal Commission appearance?

Lardy…I’ll hazard, YES!

If Shorten wins here’s hoping he calls a Royal Commission into “Iraq” and that debacle?

The Abbott government has an unusually big dissonance between its rhetoric and its action, so it might have a double dissolution election without making election harder for the micro parties. That would make any second term even more difficult for an Abbott government, but that is in the future and Abbott may be preoccupied with just getting a majority in the lower house.

Abbott is more occupied than the suggested preoccupied, so Australian citizens can relax knowing that while the Crikeyphiles may be preoccupied with their versions of politics, the chances of them and those who share their unique interpretations of politics are hardly likely to be engaged in making actual decisions of ANY variety in the real world.

I can now retire to bed knowing that while it may be that not all is well in the world, it’s a damned sight better than it could be if the Crikeyphiles had their hands on any of the important aspects of Australia’s directions.

Sleep tight.