Today the Productivity Commission has released its annual productivity update, examining the economy’s productivity performance in 2013-14 and how it stacks up to previous years and decades. The business community and the government won’t be rushing to draw attention to it, because it doesn’t at all fit the narrative of a desperate need to overhaul an inflexible, productivity-resistant industrial relations framework.

First the bad news: the broadest measure, multifactor productivity (MFP), only grew by 0.4% in 2013-14. That’s the same as 2012-13, and well below long-term average MFP since 1973-74, 0.8%. On the positive side, that’s higher than MFP since 2003-04, which has been flat or slightly negative. The productivity crisis that so preoccupied economists in recent years seems to have abated somewhat.

There’s better news on labour productivity. It grew by 2.5% in 2013-14, which is around the growth rate of 2.4% in the period 2007-08 to 2013-14. It’s also significantly higher than in the period 2003-04 to 2007-08 — 1.6%, and around the long-run average since 1973-74 (2.3%).

But wait a second — doesn’t that mean that labour productivity under Labor and its supposedly dreadful Fair Work Act grew much faster than it did under the Howard government’s WorkChoices? Well … yes. Back in 2012, Tony Abbott insisted there was a “flexibility problem … a militancy problem, and above all else a productivity problem with the Fair Work Act.” The extent of Australia’s union militancy and flexibility problems are shown by recent ABS industrial disputes and wage index data, showing both strikes and wages growth slumping.

And if there’s a productivity problem, the solution isn’t a return to WorkChoices and its dire 1.6% labour productivity growth. Interestingly, given the Abbott government was in office for nearly all of 2013-14, labour productivity actually fell compared to 2011-12 (4.2%) and 2012-13 (3.7%).

It’s likely that this fall partly reflects the continuing strength of the labour market at a time of tepid economic growth, especially outside mining and construction (next year’s productivity report, for 2014-15, will make for very interesting reading on that score), helped by flat or very weak wages growth. Employers and IR warriors like to decry weak productivity growth but ignore the benefits of labour market resilience — which flows through into higher tax revenues, higher household incomes and consumption and greater consumer confidence — all of which can be as virtuous as solid productivity growth. Yes, productivity growth is essential to future well-being, national income and economic growth, but there are times when rising employment, higher tax revenues and consumption are preferable to the hairy-chested approach of boosting productivity, cutting wages and conditions and sacking workers.

The most productive sectors during the year, according to the PC, were arts and recreation (5.4% MFP, off 8.2% growth in labour productivity) and finance (3.3%/2.9%) while utilities, transport and agriculture all experienced MFP and labour productivity declines.

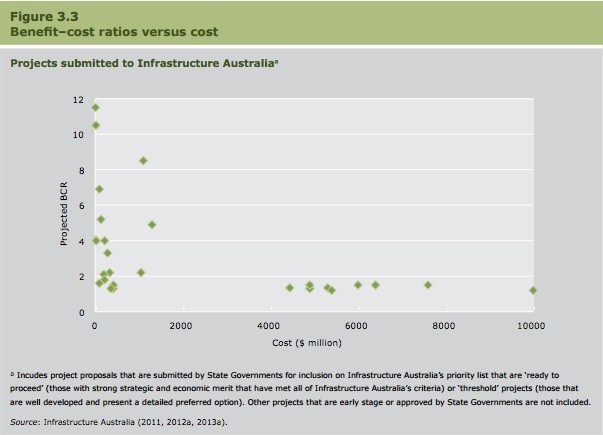

The PC also used the update to renew its criticisms of infrastructure policy in Australia, devoting a chapter to the importance of selecting the right projects for government and private investment, backed by rigorous cost-benefit analysis (and it offers some tips for attaining such rigour). And it makes the interesting point, using Infrastructure Australia analysis, that it is smaller projects that are likely to have higher cost-benefit ratios than larger projects.

But, as the PC notes about previous government infrastructure investment:

“there was a bias toward large investments despite the returns to public investment often being higher for smaller, more incremental investments. In part, this was because the private sector is more interested in financing large investments (due to the costs involved), and governments have increasingly seen public private partnerships (PPPs) as a way of harnessing not just finance, but expertise in project delivery and operation.”

What the PC leaves out is that politicians love to talk in big numbers when announcing infrastructure spending — big dollar signs, that is, with plenty of zeroes on the end, not big benefit-cost ratios (BCRs). Look no further than the East West Link in Melbourne, championed by Tony Abbott, that would have cost $7 billion, including $3.5 billion in taxpayer funding, for a BCR of — under the most optimistic assumptions — 0.84.

The report also confirms that the former ALP government and the Reserve Bank did a pretty good job in leading the economy through the shoals of the resources investment boom — there was little or no inflation despite the introduction of a carbon price and then no blowout in unemployment during the sharp slowdown and transition that followed. For all the talk at the Trade Union Royal Commission about crooked unions and dodgy officials, it is clear from the Productivity Commission’s report there has been no impact on the economy from whatever activity has been unearthed and the regulatory system that permitted it.

Good to see someone stating that productivity isn’t the only thing that matters.

Anyone who knows how ‘productivity’ is calculated will know that it isn’t something you can really hang your hat on. It is a measure, but nobody is quite sure what it is a measure of, and whatever it is, it probably isn’t ‘productivity’.

It’s worthwhile to achieve, but paying people less money or taking away their security or penalty rates unsurprisingly tends to make people less productive, not more.

Real productivity can be encouraged by providing the infrastructure that the market fails to provide, I don’t know, perhaps a world leading broadband fibre to the home internet service.

Oops!

The problem is that those damned workers insist of being able to eat.

Interesting read, though not surprising. I thought ‘productivity growth’ just meant more unpaid overtime?