We will never get to know what speech Royal Commissioner Dyson Heydon was going to deliver to self-described “Liberal-minded” lawyers in the Sir Garfield Barwick Address in Sydney later this month, but Heydon has left a few hints as to what we have missed out on.

Heydon pulled out of the event last week shortly before it was revealed he was due to give a speech at the event organised by a division of the New South Wales Liberal Party (full details here).

Included in the dozen emails Heydon released to the media yesterday is a small insight into the speech Heydon intended to give. In one email sent to the organisers of the event, Heydon said he was considering the working title of the speech to be “The judicial stature of Chief Justice Barwick viewed in modern perspective”.

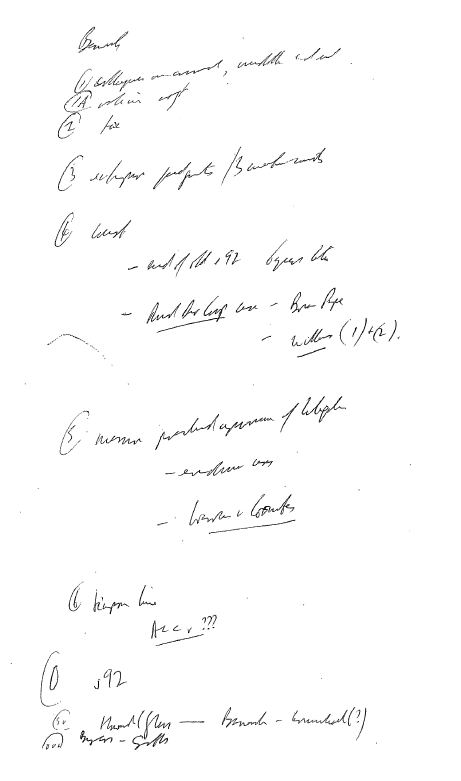

In hand-written notes that even the best pharmacists would struggle to read, Heydon also prepared potential points of discussion. Crikey has attempted to decipher some of those points to learn what Heydon was thinking of telling lawyers who had paid $80 for a dinner that was not at all a fundraiser for the Liberal Party.

The first legible point is point (2) regarding tax. Barwick was the chief justice of the High Court of Australia between 1964 and 1981, and aside from his role in the dismissal of the Whitlam government, in his time in the High Court was said to have established a differentiation between what was considered tax avoidance and tax evasion.

In his memoir, A Radical Tory, Barwick argued that citizens should be able to minimise the tax they pay.

“Consistently with this view, it has long been a principle of the law of income taxation that the citizen may so arrange his affairs as to render him less liable to pay tax than would be the case if his affairs were cast in some different form. In the language of the layman, the citizen is entitled to minimise his liability to pay tax. This is sometimes expressed as a right to avoid tax, an expression which is in contradiction to the evasion of tax, a failure to pay tax which is properly due,” he said.

“Clearly I did not accept the view that there was a moral duty to pay tax. Further, I held the view that it is for the Parliament in passing laws imposing taxation to make its meaning as unambiguously clear and certain as the use of language will permit. In the event of ambiguity in such legislation, the citizen, not the executive government, should have the benefit of that construction of the language of the statute which is most favourable to his or her interest.”

David Marr in his book on Barwick noted that “the tax avoidance industry boomed in Australia in the late 1970s as a direct result of the work of the Barwick High Court”.

In the modern context as Heydon suggested he would frame his speech, it seems the topic of tax minimisation would likely be a strong point of to draw upon, given the recent focus on multinational companies shifting their profits outside of Australia to minimise the tax they pay.

The next legible notes are “Bryan Pape” and “Williams 1 & 2”.

Bryan Pape, a law lecturer, took the then-Rudd government to the High Court in 2009, challenging the $900 stimulus taxpayer bonuses distributed during the global financial crisis. Pape argued that the acts passed by the Rudd government in order to deliver the bonuses were unconstitutional.

The High Court ultimately sided with the government, but Pape had a victory in the High Court ruling that sections 81 and 83 of the constitution do not authorise substantive spending power on the Parliament, and the power must come from elsewhere.

This feeds into the two Williams cases, relating to the National School Chaplaincy Program. Queensland father Ron Williams challenged the Commonwealth’s millions of dollars in funding allocated to support chaplaincy services in schools. Williams won the first round, resulting in new government legislation in order to fund the program. Williams challenged again and won a second time. However, the Abbott government is pushing ahead to fund the states and territories to support the program in schools.

Another case mentioned in the notes is Warren v Coombes. This case from 1979 establishes that the appellate court should give weight to the trial judge’s conclusions in deciding whether to come to a different conclusion, but can examine the facts of the case in considering its decision. The judgment states:

“In deciding what is the proper inference to be drawn, the appellate court will give respect and weight to the conclusion of the trial judge, but, once having reached its own conclusion, will not shrink from giving effect to it.”

This case is widely argued to have established that an appellate court can examine the established facts of the case itself, and can arrive at a different conclusion to that of the trial judge.

The last legible note is regarding section 92 of the constitution, regarding interstate trade. Barwick was said to have held controversial views on free trade, according to Rosalind Dixon and George Williams in their book, The High Court, the Constitution, and Australian Politics.

“In other respects, Barwick CJ was a controversial judge who championed views that were at odds with the majority of his fellow judges. He pushed an extreme private enterprise interpretation of s92 to limit the reach of goverment policy and sanctioned tax avoidance by upholding artificial schemes. Chief Justice Barwick was anti-Labor in the contrary sense that Jacobs J was pro-Labor in deciding most major cases against Whitlam Government legislation.”

Had the address not been scheduled during a time when Heydon was in charge of a highly politicised royal commission, it is likely his speech would have flown under the radar. The event would have been closed to the media, and the contents of the speech would have only been published in the lawyers’ publication Bar News.

The notes, at least, reveal Heydon was not going to speak on matters related to the royal commission, but the mere mention of the challenging of the Rudd stimulus package indicates that at least in part, the topics were political in nature at what was ultimately an event for the Liberal Party.

A member of my family went to school with Garfield Barwick shared membership of clubs with him .He also refused to speak to him.

(1) collegiate environment within court

“Unaccustomed as I am to being judged…..”

A bit of a long bow…