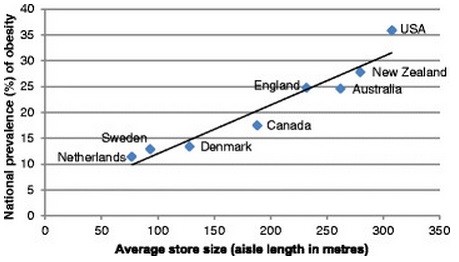

Here’s an interesting study that finds an extraordinarily strong correlation (r=0.96) between national obesity levels and the size of supermarkets in eight countries with Western-style diets — the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Canada, England, Australia, New Zealand and the United States.

The paper is titled “The correlation between supermarket size and national obesity prevalence“, and it was written by Adrian Cameron, Wilma Waterlander and Chalida Svastisalee.

The researchers took national-level obesity data from the UK National Obesity Observatory. The size of supermarkets was inferred from the combined total length of aisles in a sample of 170 supermarkets across the eight countries.

The authors say their finding suggests that “either the large supermarkets themselves, or an aspect of the urban environment or food/shopping culture that encourages such stores, is particularly obesogenic”.

They propose a possible narrative:

“Explanations for the association between store size and national obesity prevalence may include larger and less frequent shopping trips and greater choice and exposure to foods in countries with larger stores.

“Large supermarkets may represent a food system that focuses on quantity ahead of quality and therefore may be an important and novel environmental indicator of a pattern of behaviour that encourages obesity.”

I looked at data available at the UK National Obesity Observatory. It shows the age-standardised national average BMIs for the three lowest-scoring countries in the exhibit range from 19.3 to 20.3. Those for the other countries range from 28 to 33.5 (the United States, of course, is highest).

That’s a huge difference; is it possible it could be explained wholly or in large part by national differences in the average size of supermarkets?

I’d be very cautious about generalising a finding as particular as supermarket size on the basis of a sample of just eight countries. Moreover, it compares three northern European countries (two of them Scandinavian) against five Anglophone countries (four of them “New World” nations).

I don’t have a problem with using aisle length as an indicator of size, but the size of the sample is small — only eight supermarkets in England.

Leaving those reservations aside, Obesity Observatory data confirms that the Anglophone countries and a few Middle East oil states stand clear at the top of the BMI tree for wealthy countries.

It also confirms Scandinavian countries are close to the bottom end (although Japan is the stand-out with an astonishing 3.3); importantly, it shows all Western European countries fare much better than the English-speaking nations.

But I think supermarket size is an unlikely explanation of the differences in BMI. It’s easy to find a variable that fits a distribution like national BMI — the ages of the members of my extended family would fit it quite well. Last week I referenced research that found using transit makes you short!

A better starting point is to ask why some countries — particularly the Anglophone ones — have such high BMIs compared to other developed countries.

It brings to mind other exceptional characteristics of English-speaking countries, like why they have such high infrastructure costs or why they dominate popular music.

There are a number of possible explanations. One is differences in built form. It’s likely that average supermarket size is a proxy for more significant variables, like mode of transport and the density of activities.

Denser places are likely to have smaller supermarkets and greater reliance on active modes of transport than private vehicles; this might contribute to lower obesity rates through higher levels of incidental exercise.

It’s far more likely though that differences between wealthy countries are primarily a product of what’s eaten e.g. see here, here and here. They might arise as a consequence of factors like variations in the way food is taxed, in racial and ethnic composition, in cultural aspects like diet, or in inequality (within developed countries, obesity is higher in lower socioeconomic groups).

Like the debate around infrastructure costs, it’s hard to pin down a single cause that explains most of the differences. One possibility advanced by these Scandinavian researchers is that “societal organisation at the macro level seems to matter”. They say:

“A high degree of market-liberalism has been suggested to increase the prevalence of obesity in the population. Inequality within countries seems to be positively associated with an inverse gradient between socioeconomic position (SEP) and overweight and obesity (OWOB).”

They speculate that the superior performance of the Nordic countries in relation to obesity may be due to “the positive features of the Nordic welfare state”, like “socially egalitarian ideals and a reputation for low levels of inequality”.

It’s not the size of the Supermarkets, it’s the size of the portions. If you shop in a supermarket in Beijing the de-facto packaging size assumes a 3 person family (Mum, Dad & one child) despite extended families often living as one.

It is easy and logical and cheap to buy small portions. I would suggest it is also in some way (perhaps unconsciously) planetarily responsible.

In Australia 2 litres of milk at Coles or Woolworths is cheaper than one litre. Large chips and chocolate and Coca Cola and the like are cheaper the larger the quantity you buy. So what do you do in Australia? To save money you buy large. To ensure your saving is actually made you need to consume large. There is something gross (in both meanings of the term) about this.

There is also the Costco influence as well… huge behemoths with products on offer from toilet paper to tools and sausages to spas.

Suited more to the obese American market than ours they seem (at least in Melbourne) to be adding to overspending and overconsumption that the US does so well.

Not here. We dont need nor want you. Go away.

So countries big in fat have big fat supermarkets?

This is about as obvious as stating that pedophiles enjoy scouting and religious pursuits whilst attending Geelong Grammar, or that 99.999% of skin cancer sufferers have at some stage been in the sun.

Since the Netherlands has the lowest figure, it is therefore obvious that the presence of large numbers of dykes is extremely beneficial for a community’s BMI.

I love statistics.