Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has the all-clear to use encrypted messaging apps like Slack for non-classified communications, but he has been warned by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet to be careful to comply with record-keeping and freedom of information laws.

Earlier this month, it was revealed Turnbull, in addition to using his own email server for government business, had encouraged his cabinet ministers to use Slack, a communications app that has private and public channels for members of an organisation to discuss business, gossip, or just organise the staff birthday parties.

On October 9 Turnbull said he believed it to be above board, provided classified communications were still conducted the usual way, but he did not get the official OK from the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet until October 13.

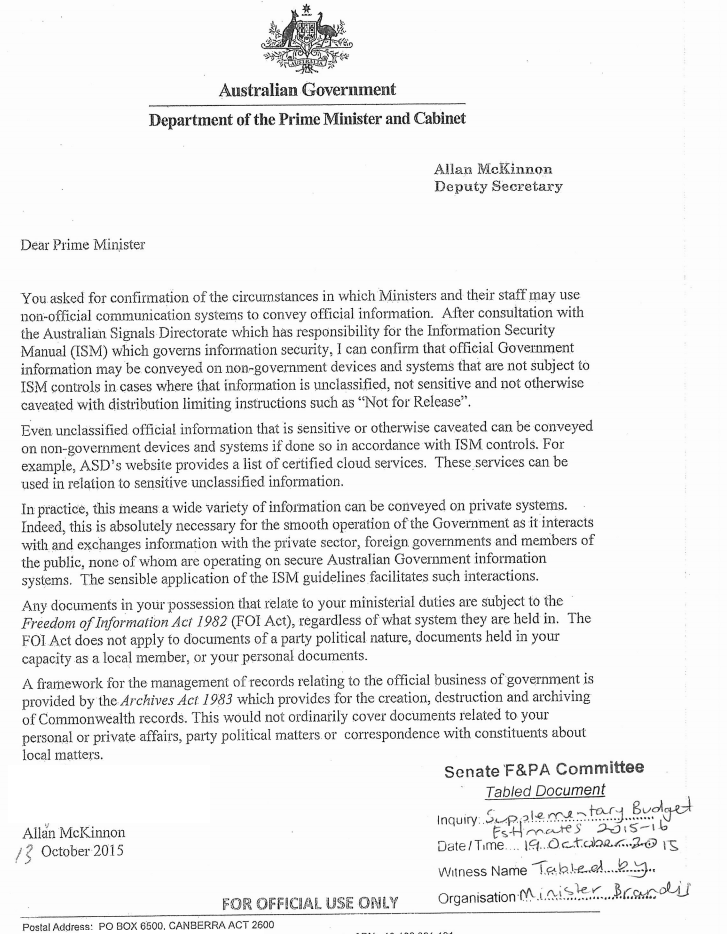

In a letter tabled in Senate estimates hearings last week, PM&C Deputy Secretary Allan McKinnon told Turnbull on October 13 that non-classified information could be conveyed on “non-government devices and systems”:

“Even unclassified official information that is sensitive or otherwise caveated can be conveyed on non-government devices and systems if done so in accordance with [information security management] controls.”

McKinnon cited the Australian Signals Directorate’s list of certified cloud services providers. That list includes companies such as Amazon and Microsoft as being approved by ASD for government use. This means Turnbull’s email server, believed to be hosted by Microsoft, has been approved. McKinnon said the mere fact that most people the government communicated with didn’t use secured government systems meant many communications that happened within government could be on non-government systems:

“These services can be used in relation to sensitive, unclassified information. In practice, this means a wide variety of information can be conveyed on private systems. Indeed, this is absolutely necessary for the smooth operation of the government as it interacts with, and exchanges information with the private sector, foreign governments, and members of the public, none of whom are operating on secure Australian government information systems.”

McKinnon indicated that while communications that were not party political, conducted as a local member, or personal, would not be subject to freedom of information or archive laws, all other communications, particularly for ministerial activity, would potentially be subject to the FOI Act, and management of the records would fall under the Archives Act.

In estimates hearings last week, McKinnon expanded further, stating that Slack and the self-destructing messaging app Wicker offer “end-to-end encrypted messages” and a “heightened degree of security and privacy”, but he admitted the department had not conducted a security assessment on Slack or Wickr to determine whether either could potentially be compromised:

“I am not aware that there has been a formal assessment of those. I would say that there is system development under way all the time across the Commonwealth public service. Different agencies are looking at different ways to improve communications and make them more secure. With that app in particular, I could not say.”

Attorney-General George Brandis shrugged off the suggestion that using Wickr, where messages are deleted at a time of the user’s choosing, would not be available to freedom of information searches.

“FOI depends upon the existence of a document, whether in conventional form or electronic form. If your document, in whatever form, no longer exists, it no longer exists … The FOI Act and the Archives Act apply to documents which are extant at the time of an application. If there is no extant document, there is no extant document.”

Director-general of the National Archives of Australia David Fricker told Crikey it wasn’t the format of the communications that mattered for record keeping, but the type of communication.

“Digital communications over applications like Wickr or social media are generally subject to the same business and legislative requirements as records created by other means. Facilitative and transitory records and records retained in other systems can usually be destroyed as a normal administrative practice,” he said in an email.

“It’s important to note here that the business of government is largely conducted in a digital environment, and right across government we are adopting digital technologies that improve cost effectiveness and make services more convenient for the citizen. The use of non-government platforms is entirely consistent with this digital transformation agenda, and the National Archives provides advice, policies and training to ensure that it can occur within an Information Governance framework that preserves those records necessary to retain the memory and evidence of government activity.”

Reports that cabinet had shifted to Slack were greatly exaggerated, according to Brandis, who denied there had been a “systemic shift” for the cabinet to use Slack. But the Prime Minister is far from the first in government to consider non-official communications applications. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade first assistant secretary for public diplomacy and communications told an estimates hearing this week that officials in China use the Chinese application WeChat for official but unclassified communications:

“We do have two official WeChat channels in China, which we use for public diplomacy purposes, which are to engage the public, but they are not as part of our official internal messaging system.”

Department secretary Peter Varghese said that DFAT has two systems, with one for classified and one for unclassified information, but the department needed to be flexible to allow staff to communicate in other ways if unable to access official systems:

“There may be circumstances where information needs to be conveyed and an officer does not have access to either of those systems, particularly if they are overseas or attending a meeting in some place where we do not have a mission, and it could be that there is a requirement for them to get information back to Canberra that is not classified, and they may use a Hotmail account, a Gmail account or some other account.”

Crikey is also currently seeking Slack communications from the Digital Transformation Office, Turnbull’s agency charged with moving government into the digital era, and a well-known user of Slack. It is believed that communications may be provided under FOI, but the usernames of staff members are likely to be redacted.

Australian Ci5tizens can rest easier, Josh, knowing it’s Turnbull not his critics who’s dealing with such complex issues.

Turnbull and Josh Frydenberg claim that there’s a “strong moral case” for coal export to India. I think that there is also a strong moral case to use verified numbers when arguing the case. With his Honours degree in economics, Frydenberg should appreciate this. Turnbull is yet to demonstrate his numeracy credentials beyond the personal.

OK – there’s lots of numbers out there and tracking down some reliable ones can be quite a task. It took me all of 10 minutes on Google to come up with this extensive analysis of the Indian situation http://www.vasudha-foundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2)%20Reader%20Friendly%20Paper%20for%20USO_Status%20of%20Rural%20electrification%20status%20in%20India.pdf.

Most of the numbers in this extensive report relate to energy costs in 2011, which are more durable for coal than for solar, which is rapidly declining.

Given that the LNP ascribes to Hoover’s dictum that “while there’s smoke coming out of the chimney then there’s a chicken in the pot”, we’ll leave aside the climate change issues and look at the raw numbers.

The “electricity poor” of India are mainly in several hundred thousand villages averaging about 1,000 people per village and averaging 10km apart. This dispersal is the crucial issue, as it is not the generation cost that is the issue – it’s the transmission costs – as Australians know from their high electricity prices due to “network gold-plating”. Even a copper-clad network in India costs about 3cents/km/kwh. At about 10km between villages, it adds about 25cents/kwh to the basic generation costs. So the actual costs of providing centralized coal-generated electricity to (presently) non-gridded villages is similar to Australian electricity costs – about 25-35 cents/kwh.

And solar? The reality of these villagers is that although they would love to have copious electricity to power lights, stoves, fridges and TVs, their poverty (less than a dollar-a-day) means that the basics of a few lights is all that they can aspire to in the short- to mid-term. This is like the villages that I saw in Peru a few years ago – that lighting means education and education means poverty-alleviation.

The solar numbers: The present panel price of about $70/kw gives a 20-year (panel lifetime) price of about 4cents/kwh. To that must be added a storage battery price (1kwh deep-cycle batteries in India cost about $150 retail), which with a 10 year lifetime is about 4cents/kwh. Fancy, larger “Powerwall” batteries are not considered). Add to this battery chargers (wiring considered common with coal, so not included) and we have an all-up price of about 10cents/kwh. All at present prices, which are declining at about 20% per year.

Even if my numbers are optimistic, we are looking at local/solar being about HALF of the price of networked/coal.

Note that this analysis looks directly at the poor villages that presently do not have electricity – not providing extra electricity for the rich in the cities.

Anonymous Jedimaster, you could dream about the day you matched Turnbull, but it would be a hopeless dream.

The war on transparency in Government continues apace just as, ironically, does the war on citizens’ privacy.

Soon we will know next to nothing about our leaders that they do not censor, and they will know everything about us despite any attempts by us to censor it.

The good news for you, drsmithy, is that Australian Governments aren’t as disinterested in the welfare of their Citizens as you assume to be an unquestioned given.

Australians can be grateful our Security establishments have done and continue to do such a sterling job. In the past it was largely frequently sincere but almost always deluded varieties of Marxists who posed threats, but nowadays it’s largely fanatical fundamentalist terrorists and their misguided fellow travellers who do most damage to democracies.

Citizens’ privacy is important, but it’s not an absolute as any perceptive educated observer would tell you — if, of course you were willing/able to listen objectively.