Everything’s on track to reduce global CO2 emissions in an orderly fashion, says the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), except for the fact that the world is likely to suffer close to a 3-degrees rise in temperature by 2100, and possibly greater. Meanwhile Australia’s contribution has been judged one of the most inadequate, putting it well behind numerous developing countries, facing a raft of social and economic challenges, with the “Direct Action” policy making us the worst performer in the industrialised world.

That’s the takeaway from the just-released “synthesis report” of the UNFCCC, produced ahead of the Conference of Parties 21 (COP21) conference in Paris, beginning at the end of the month. The “synthesis report” brings together individual country reports on their emissions policy, the so-called “intended nationally determined contributions” (INDC) provided by 155 countries covering 88% of the world population.

The UNFCCC is presenting the final figures in a straight fashion, but wrapping them in something of a bow, with UNFCCC executive secretary Christiana Figueres calling them a “determined down-payment on a new era of climate ambition”, which appears to be a double-distancing from a statement of actual achievement.

In fact, the synthesis report projects, on the INDC figures, a rise in temperature of 2.7 degrees by 2100, way above the 2-degrees limit that has been set as the de facto boundary between major damage, and the start on the road to catastrophe. Yet even the 2.7 degrees figure has been disputed, with India’s Centre for Science and Environment arguing that the INDC projections, when recalculated, yield a climate rise of more than 3 degrees by 2100.

The temperature rise between 2 and 3 degrees produces a series of effects far beyond the impact of a below-2-degrees rise, including the creation of “super El Ninos” and the fiery destruction of the Amazon rainforests. Above 3 degrees, according to a collation of the evidence by Australian commentator David Spratt, the climate goes into an autonomous process of self-transformation, towards a hotter planet, with sea levels rising up to 25 metres and mass habitat destruction that may well be beyond the capacity of humanity to reverse or control.

The synthesis report anticipates that, even with the application of measures outlined in the INDCs, global aggregate emissions will be around 40% greater in 2030 than they were in 1990, but that the growth rate of such will slow — down to around 15% in the 2010-2030 period — compared to 24% in the 1990-2010 period. Emissions per capita will actually decline by around 8% compared to 1990. The world is getting greener, but more people are getting the chance to use brown power.

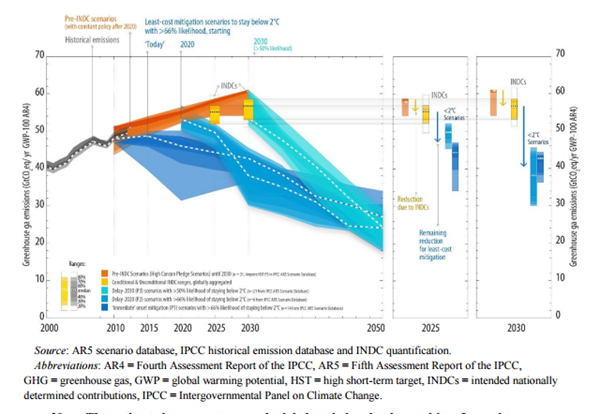

To keep the temperature rise below 2 degrees by 2100, and on the “least-cost” pathway as envisaged by the INDCs, emissions would have to come down by about 3% a year, every year from 2030 onwards. Starting earlier, as this graph shows, would require only a 1.6% average reduction from now. However, as the graph notes, the turquoise 2030+ pathway is the most likely situation we will find ourselves in — and as unlikely to be followed as any of the other ones.

The sharp pitch of the graph should make it clear that it is not likely that we will keep the temperature rise under 3 degrees.

Australia’s INDC has come in for particular criticism, being judged “inadequate” by Climate Action Tracker, the aggregating analysis site. CAT points out that Australia’s commitment to a 26-28% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030 would bring our emissions back to roughly equal to our 1990 levels, and possibly as much as 5% higher. Most industrial countries have made proposals that will take them significantly below 1990 levels. Only Australia, Canada and New Zealand — the settler dominions — fall short of that, projecting a white, anglo-derived privilege into the 21st century. However, of that dismal club, we are the worst. Not only are our targets terrible, but we don’t even meet them. As CAT notes, on the basis of current policy rather than targets:

“Australia’s Direct Action Plan does not put Australia anywhere close to a track that meets its INDC 2030 target. The additional funding announced in August 2015 by the government for post-2020, should it be re-elected in 2016, would reduce this projected increase by only 2%, to around 25% above 2005 levels (equivalent to 57% above 1990).”

Some countries that had been with us in the arseholes club, such as the US, have now left it, according to CAT, thanks to recent changes in policy. And other countries such as Mexico, committing to a 22% reduction of emissions below the 1990 baseline, put us to shame.

With these dismal assessments coming at the same time as the government voices its support for new coal mines and coal, in the words of the Prime Minister “being a major fuel source for many years to come”, the backwards-looking commitments at COP21 — ours especially — are starting to look less like a down payment, and more like that Australian standby, negatively geared with zero deposit and no obligation.

We continue to use the drug dealers excuse that if we don’t sell it someone else will.. and our coal is much cleaner..and its stopping drownings..sorry.. its alleviating world poverty..and anyway our emissions are a drop in the bucket…direct action is a winner..and all this from a new agile PM who accepts the science and the urgency.. apparently

Abbott, when in opposition & in government, argued Australia has such a comparatively tiny population therefore an almost negligible contribution to make any difference to global emissions.

But in the next breath the boast is of our importance on the world stage eg: hosting the G20, gaining a seat on the UN Security Council.

Can’t have it both ways – Oz is either relevant or not.

Who cares what Climate Action Tracker (CAT) thinks.

They are not part of the UN. Just a lobby group who doesn’t believe land-use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) is a valid way of reducing emissions. (As if the world cares how emissions reductions are achieved)

That’s right models don’t lie!

Scott

No, they separate LULUCF from more direct policy measures, on the grounds that offsetting carbon is different – and as policy highly variable – to reducing the amount that gets into the atmosphere in the first place.