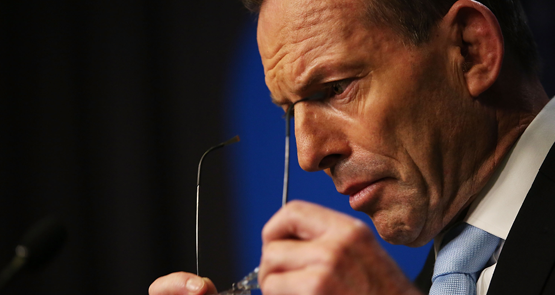

Tony Abbott’s aggressive Margaret Thatcher lecture in London last week, widely derided by both sides of politics and on both sides of the world, has sharpened even further the dilemma now facing the Liberal Party.

The performance was one of a man grasping for relevance, a tragic echo of the interview on the ABC’s 7.30 the week before his demise, where his answer to questions on the economy was “we stopped the boats”. Indeed, his ABC performance is likely to have provided ammunition for the Member for Wentworth, as he shored up the numbers for his successful putsch.

The sight of an ex-prime minister from a former British prison colony (yes, that’s what many of them still think) dumped by his own party after only two years, lecturing a Tory Party, whose own Prime Minister David Cameron was returned this year with a healthy majority, has dramatically raised the stakes of the conundrum faced by Liberal elders.

Their problem is, with apologies to Rodgers and Hammerstein,“What are we going do about Tony”?

Fairly credited for leading the Coalition back into government on a campaign of relentless negativity, he may in future years be credited for setting up the Turnbull ascendancy. But such prognostications, so early on, are for the very bold.

Having witnessed the malignancy of Kevin Rudd’s fury smouldering away in parliament, first as foreign minister — a move made necessary by Team Gillard’s singular error in not removing him in a party room ballot — and then as a backbencher, senior Liberals have been working on a graceful positioning strategy for Abbott since the Turnbull coup.

The running of the Abbott project has been taken on by John Howard and senior Liberal Party heavyweight Tony Clark, former NSW managing partner of KPMG Australia.

Clark has been so close to Abbott he was one of the few regulars at Abbott’s annual post-budget dinner at Parliament House, reserved exclusively for Coalition MPs and a handful of others educated by the Catholic Jesuit order. Like Abbott, Clark attended Sydney’s St Ignatius College, commonly referred to as Riverview.

Crikey understands that Clark spoke to Abbott about a senior position either as chief executive or director at Ramsay Health Care Ltd , where Clark is on the board. Abbott is also said by people familiar with the discussions to have had no interest in the job as ambassador to the US, which appears set to go to Joe Hockey.

At a dinner with Clark and Howard three weeks ago, other options were discussed but still Abbott appears unsure what he wants to do, still struggling with a coup neither he nor his advisers saw coming until it was too late.

With only two years as prime minister under his belt he is not an internationally marketable commodity like Howard, Keating and Hawke. Rudd has ridden his sinophilia and relentless networking to a job at the Asia Society. Gillard appears to be cleverly leveraging her position as Australia’s first female prime minister. Abbott has no overriding policy obsessions or success — except for “stop the boats”, which, as former senior bureaucrat John Menadue pointed out in Crikey, had actually been halted before Abbott became PM.

Abbott’s state of mind since his September party room defeat has reminded some close to him of the period following the Coalition’s November 2007 defeat by Kevin Rudd.

In September 2008, when Malcolm Turnbull replaced Brendan Nelson as Liberal leader, Abbott was still seemingly unable to come to terms with the loss of government. He was despondent, confused and unfocused on work.

He had lost his late-period political mentor, John Howard. Let’s not forget that Abbott, both the man and politician, is the true heir to the late Democratic Labor Party leader Bob Santamaria; a man wedded to ideology but never tested at the ballot box.

Santamarias’s insistence on ideology taking precedence over the basic tenants of successful politics — which involves dialogue with opponents, finding middle ground and compromise — would come to characterise Abbott’s premiership and sow the seeds of its fracture.

Ironically, Malcolm Turnbull was one of those who urged his colleague to pick himself up as the party needed him. Just as Howard and Arthur Sinodinos would later counsel Turnbull himself to hang tough.

It was Turnbull who suggested a way Abbott could reinvigorate his interest in politics: write a book. The result was Battlelines, and the rest is history.

Abbott’s speech, along with the public carping of dumped cabinet colleagues Eric Abetz — who, before Turnbull toppled Abbott, was being positioned for the gig as ambassador in Berlin — and Kevin Andrews have only served to emphasise the change in the parliamentary Liberal Party that voters are embracing.

This time around, Abbott faces a tougher task, and on the evidence of last week’s speech — lauded by nationalist and xenophobic British party UKIP — runs the risk of being pigeon-holed as standard-bearer for the far right, and that would be a shame.

“runs the risk of being pigeon-holed as standard-bearer for the far right, and that would be a shame.”

A shame? Not really. He is purely far-right, so now all the blinkers and PR are gone from his life, we finally see that he is more at home at a fringe sideshow of a PEGIDA rally (talking about detention centres, cruelty, shootings and closing all borders no matter what is coming gets him in as a reserve)

All this ‘oh that’s a shame’ is one reason I feel that Australia is behind in the world. Abbott, internationally, is classed in the same mould as Orban in Hungary, highly right-wing, with fascistic leanings, but not as Orban (unable to change the constitution). It was obvious from the start, but the media and talk here never pinned him as he would have been overseas.

You’d never see “oh what a shame Orban is pidgeonholed as a standard-bearer for right-wing nationalist parties” with his fence building and militartistic reinforcement against refugees. What a shame, how embarrasement.

I fail to see why it would be a shame for Abbott to be “…pigeon-holed as standard-bearer for the far right…”. It is as precise a description of the man as I have ever seen.

On every possible ideological measure Abbott was as far right as anyone can get in politics in a western nation these days:

Rabidly anti-Muslim,

In absolute opposition to marriage equality,

Openly sexist failing to appoint more than token women to cabinet (and awarding himself the role of Minister for Women)

Resolutely against any recognition of anthropomorphic global climate change,

Reintroducing Knighthoods and then conferring on the husband of the English Monarch, the list goes on.

None of these actions are those of an enlightened conservative leader. However had he pursued or advocated 1 or 2 of them he might have some claim to sanity. He pursued all of them and more, demonstrating very clearly that he was not only a standard-bearer, but one of the standard-bearers.

The sooner the Liberal Party Grandees find him a sinecure somewhere away from the media spotlight, the sooner he can be consigned as the answer to the question Who was the stupidest and least effective Prime Minister in Australia’s history in a pub trivia night.

Given Australia’s large role in Antarctica, it seems remiss not to have an ambassador posted there.

Weighing up Abbott’s talents there are two roles which immediately spring to mind:

– another book, this time on the joys of cycling

– a speaker on the dinner circuit, the specialist subject being The Art of Wrecking.

Please Mr Abbott.. stay in the Parliament and continue to do what you do best..wreck governments..