What if I told you there was a way to raise GST and make it fairer? What if I told you the answer was right under our noses? What if I told you the answer makes perfect sense but could make you feel very uncomfortable?

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull wants to raise GST, and so do several states. It is plausible a hike in the rate and a broadening of the base will happen even if it is very unpopular, and even in the face of opposition from federal Labor.

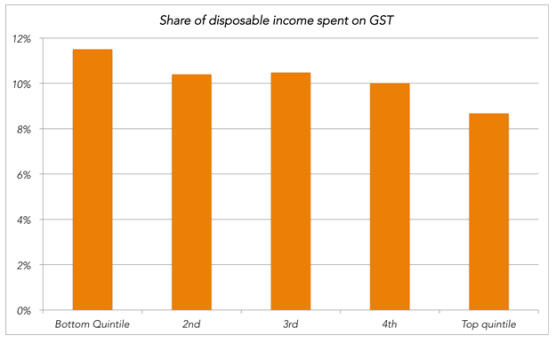

But the GST is a regressive tax. Everyone knows it. The share of income spent on GST is higher for the poorest than the richest.

On Twitter, people were calling raising the GST a class war. I don’t agree that better funding state governments — which spend on hospitals and public schools — is class war.

But yes, raising the rate of GST creates a trade-off with maximising the disposable income of the least well-off.

The only reason to pick GST as the tax you want to raise is that it is economically efficient. Swapping our other taxes for GST should, in theory, make the economy grow faster. That can make everyone better off.

This chart shows GST is more efficient than stamp duties and company tax.

So how can we hike this efficient tax without making the poorest worse off? The answer is by finding something rich people spend more on than poor people, and extending the GST to it.

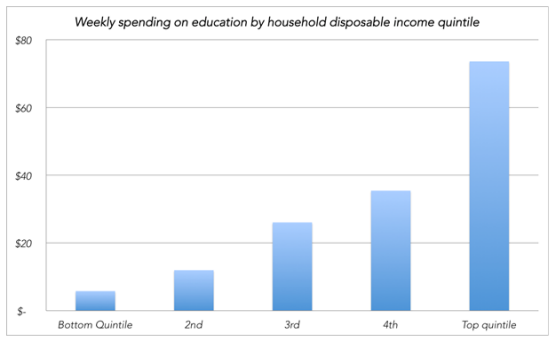

Rich people spend more on almost everything than poor people (except tobacco). The top 20% spend eight times as much on hotel rooms as the bottom 20%, for example, and six times as much on insurance.

But those categories are not the most skewed.

The rich spend 12 times more on education than the poor. And that spending is tax free.

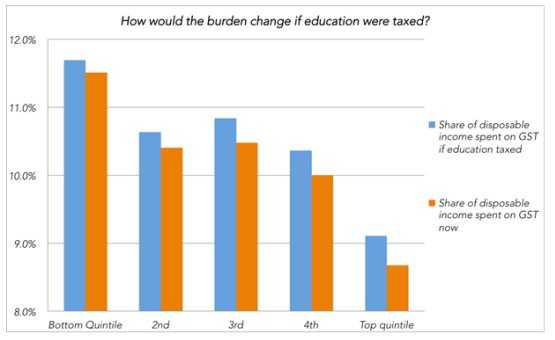

It might feel counter-intuitive but the fairest change we could make to GST is to start taxing education: 10% extra on maths class, 10% extra on history; 10% exams; 10% on school sport.

It would cause the GST to become a more progressive tax. (Which is to say it would still be regressive, but less so. The increase in tax paid by the richest would be more than the increase paid by the poorest.)

One objection is that this will hold back the less well off by making education more inaccessible. That argument cannot stand while the government is providing free universal secondary school education.

The other big objection is that it would be more efficient just to reduce subsidies to private schools rather than taxing them. To which I say: why not do both?

Taxing education could raise $3 billion, according to accounting firm PwC. That will be extremely valuable to states starved of money for public transport hospitals and roads.

This idea might not be popular per se, but when it comes to raising tax, nothing is.

In the cut and thrust of the GST debate, nobody will get exactly what they want. Reformers are likely to start with an ambit claim of broadening the GST to food, education and health while also hiking it to 15%.

After a bit of give and take, they could end up with a 12% GST that still excludes food but now covers education.

Choosing taxes to raise is a matter of choosing the least unpopular. Raising billions by taxing education might feel very strange but might easily be the path of least resistance.

Can Turnbull raise the rich share of the tax burden and still be PM?

50% chance?

How does it compare to stopping Government funding of private schools ?

GST is a fundamentally regressive tax. “Compensation” from raising it will not be adequate, will not be sustained and recipients thereof will be demonised at every turn by conservatives at every turn.

With so much other low-hanging fruit to be grabbed, and the much more efficient and equitable LVT option, any arguments in favour of increasing the GST are just ideological.

You’ve missed the forest for the trees. Taxing education may be a short term fix for a budget deficit, but, it creates a long term deficit in the overall level of education, which has a direct impact on competitiveness. China, for example, (still) makes education free. They will be the nation churning out the scientists and engineers, while Australia is being literally taxed into stupidity.

Here’s a thought — right under our noses, too. Cancel that $24 billion contract for a bunch of useless military aircraft we don’t need and that don’t work all that well. Use the money to FUND education, making it MORE available to all, not less so.

Oh, and here’s another one. Instead of spending billions each year maintaining what amount to “black sites” (ala CIA) where we keep asylum seekers, or settling them in other countries, spend that money to settle them HERE, put their talents and energies to work HERE for Australia.

One last thing: stop molly-coddling the likes of Apple, Microsoft, Google, mining and Big Oil. TAX THEM! They’ve grown rich off of Australia’s natural resources and from an infrastructure that Australian’s built. Australians — not any of them.

Instead of giving tax breaks to the rich and continuing to tell those further down the ladder that the benefits will trickle down, it’s time we admitted that this is upside-down. Give the biggest breaks to those earning the least, and tax top earners. Our PM would make a great first example of this.

The Howard Government went to the 1998 election which centred on the GST and won a second term with its March 1996 majority of 45 seats reduced to 12 suffered a 4.6% swing against it and lost the popular vote 51% to 49% .. a result that might have been worse if some voters had realised that the then Democrats would actually pass it through the senate.. Shortens luck might be about to turn..

The problem with this article is that the result would still be low income people paying more in GST than they are now. I don’t think that making it ‘fairer’, i.e., less differenc in percentages of income, makes up for that fact.