Ever by the fraught standards of minority government, Annastacia Palaszczuk’s Labor administration in Queensland has faced an unusually challenging environment since it took the reins after the shock state election result in January.

As its first anniversary in office looms into view, the government’s latest round of trouble could potentially eclipse all that came before, as the issues involved have a direct and powerful bearing on the self-interest of the parliamentary crossbench.

The catalyst is a looming electoral redistribution, the process for which will begin in mid-February.

Like any redistribution, this one will be shaped by patterns of growth across the state’s various regions since the existing boundaries were set in place seven years ago.

The overall story is a familiar one of urban boom and rural stagnation, despite being complicated in Queensland’s case by the strong growth of retirement magnets such like Cairns and Hervey Bay.

On balance, this tends to make redistributions happy occasions for Labor, given its concentration of support in urban areas.

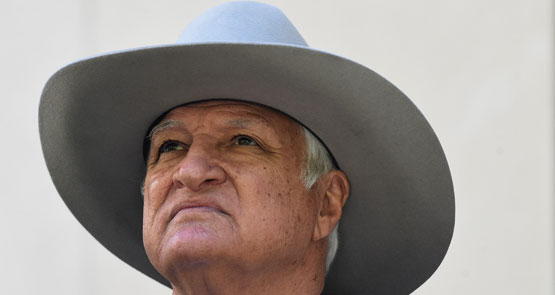

However, it’s a very different story for Katter’s Australian Party, whose two members account for two-thirds of the parliamentary crossbench (another independent, Nicklin MP Peter Wellington, holds the position of speaker).

In the short time that remains before the redistribution starts, the KAP members, Rob Katter (son of Bob) and Shane Knuth, are very keen to see the rules rewritten in a way that puts their rural and remote electorates on a firmer footing.

The opposition stirred the pot a few months ago by introducing a bill that sought to give the KAP what it wanted.

This was to be achieved by giving the redistribution commissioners discretion to increase the size of parliament from 89 seats to 94, and softening requirements of equality in voter numbers between different electorates — otherwise known as the “one-vote, one-value” principle.

As always when the opposition’s numbers align with the KAP’s and against the government’s, all eyes fell upon Billy Gordon, the Labor-turned-independent member for the Cape York electorate of Cook, who provides Labor with its decisive 44th vote on the floor of parliament.

Gordon told parliament that while the bill’s proponents were “well motivated in their endeavours to improve representation to rural and remote regions of the state”, he could not vote in favour of “more politicians” and “a move back to a gerrymander”.

But when the KAP members tried again by introducing a new bill of their own last week, Gordon voted in favour of a motion to ensure the bill would be put to a vote in good time for the redistribution.

The prospect of a government being held over a barrel on matters involving the very constitution of parliament raises basic questions about the extent to which parliamentarians should be free to set the rules of their own game.

In keeping with the Westminster system’s principle of parliamentary sovereignty, Australia’s parliaments have few constraints in determining their own size, shape and manner of election.

The High Court has generally taken a hands-off approach when such matters have come before it. A notable case in point was its rejection of a Labor-backed bid in 1975 to have the court mandate the “one-vote, one-value” principle, after the Whitlam government legislative efforts fell foul of a famously obstructive Senate.

However, the court has taken a more activist approach to upholding democratic principles in recent times, and has demonstrated a particular readiness to strike down legislation that seeks to undo earlier advances.

The KAP’s new bill sidesteps such questions by limiting itself to a simple five-seat increase in parliamentary numbers. But in doing so, it introduces the no-less formidable political obstacles involved in selling the public on the need for more politicians.

Should the government ultimately suffer a defeat on so fundamental an issue, Westminster convention requires that it should resign or call a fresh election.

This is of particular relevance in a state where the Westminster system survives in an unusually pure form, without the impurities of fixed terms or a strong upper house.

A couple of months ago, when polls recorded Labor opening a solid lead on the back of its own post-election honeymoon and the infectious unpopularity of the Abbott government, the government might well have been tempted by the thought of a snap election fought over an Opposition-backed plan to add more snouts to the parliamentary trough.

But in the wake of the Malcolm Turnbull ascendancy, polling conducted nationally suggests the surge in Liberal support is having substantial spillover effects at state level.

That could well cause Labor to decree that adherence to musty old constitutional conventions is not in Queensland’s interests — something it can very easily do, so long as it retains Billy Gordon’s vote on the decisive questions of confidence and supply.

As has been the case since shortly after the election, the ball remains very much in Billy Gordon’s court.

Just a little technical issue there, the KAP bill is calling for an increase of 4 seats, not 5.

http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/work-of-committees/committees/LACSC/inquiries/current-inquiries/08-ElectoralIRAAAB15

Can’t these plonkers count. An even number of seats? It’s just asking for trouble.

I’m suss on these Morgan figures, how did the preference allocations work? Morgan seems hardly to have moved since the election which seems quite out of kilter with other published polls? Anything that relies on 2012 preferences is likely to be unreliable, at least.

“Make Bowen the Capital!” exclaims BobKat.

I’ve got a doctorate in Queensland constitutional history so I know what I’m talking about. The electoral system for Queensland’s sole chamber of parliament does not approach “one vote, one value” because in a system of single member electorates, “one vote, one value” cannot exist. When 50 per cent plus one of the two-candidate preferred vote is all that is required to elect a member of the Legislative Assembly, then all votes for the remaining candidate who gets 49.99 per cent or less after all preferences are distributed are wasted AND HAVE NO VALUE WHATSOEVER, regardless of whether each constituency has roughly the same number of voters, and that ain’t true in Queensland either where vestigial remnants of the zonal electoral system remain nearly 30 years after Fitzgerald. By contrast, a quota preferential system of proportional representation in multi-member constituencies such as the single transferable vote (STV) often referred to (erroneously in my opinion)in Australia as “Hare-Clark” virtually requires all candidates to achieve the same number of votes to be elected. STV gives the voter maximum choice and the maximum possible influence of their vote in the election of one or more candidates. It also tends to produce parliaments without single-party majorities, so diluting the near total control of the executive government over the legislature. This is particularly so in Queensland where there has been no second chamber (upper house if you prefer) since 1922.

Both Labor and the LNP have been guilty of both gerrymandering and malapportionment in the past, and I’ve no doubt Campbell Newman would have gotten around to it eventually had he lasted, based on his attacks on the CMC and the Supreme Court, both of which were akin to Mugabe in Zimbabwe at his vilest.

Now, Katter’s – and his old man’s too – roots are/were in the Queensland ALP of Theodore, McCormack,Forgan Smith and Hanlon, all of whom practiced electoral manipulation on a wide scale, either by failing to hold redistributions, or by positively legislating for lower enrolments in those rural and regional areas where their vote was most heavily concentrated. And a return to that is precisely what Katter and Springborg are about in this exercise. But I think that, in so doing, they are ignoring the lessons of the utterly failed and disgraced premiership of Can-Do-A-Deal Campbell Newman, who from day one set Queensland on a course back to the root-and-branch corruption of the Bjelke-Petersen era, a period so debauched that a grossly corrupt Commissioner of Police could advise a grossly corrupt Premier on electoral redistributions which is really fucking scary IMHO. If Springborg wants to go back down that path – and I reckon it’s in his DNA – then the voters will again savagely turn on the LNP, and the next Queensland state election will be a landslide against the conservatives on a par with Beattie’s victory in 2001. And after that … Queensland will still have an elected, one-party dictatorship perhaps relatively benign as with Pineapple Pete, or utterly grotesque and Fascist as with Bjelke-Petersen and Can-Do-A-Deal. There are two realistic choices for Queensland: adopt STV or something similar for the Legislative Assembly, or bring back an upper house elected by STV to counterbalance to overwhelming dominance of the executive on the Legislative Assembly.