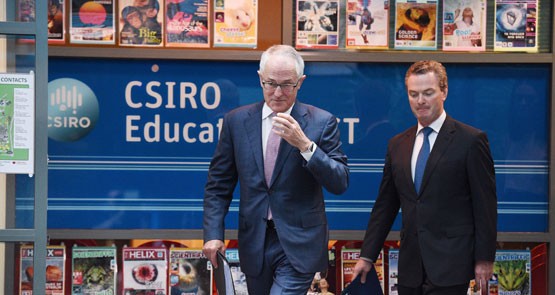

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s shiny new innovation package restores science funding so savagely gutted by Tony Abbott, but it might be too little, too late.

While the restoration of funding to the CSIRO in the $1.1 billion National Innovation and Science Agenda has been welcomed, after the loss of one in five staff, the loss of some research projects, and the planned closure of eight sites, it is cold comfort for some. The innovation package announced yesterday included $200 million for a CSIRO innovation fund to co-invest in new companies capitalising on research created by Australian institutions. There is also $20 million to expand CSIRO’s accelerator program for commercialisation for research, and $75 million for Data61, the technology research commercialisation entity (formerly known as NICTA) brought into CSIRO after NICTA lost its government funding.

The funding clawback will no doubt bring relief to some in CSIRO, who had watched approximately 1400, or 20%, of their colleagues pack up their desks during the Abbott government era of budget cuts to CSIRO and NICTA as a result of the former government’s policy. Morale was at an all-time low before the announcement, as CSIRO tried to plug the funding gaps with short-term work for long-term research. One staff member told the CSIRO’s union, the Community and Public Sector Union, last year:

“CSIRO is quickly destroying its R&D capacity and limiting itself to consulting type work for which it is completely ill-suited due to massive overheads. We could be assisting industry in taking up new initiatives to improve productivity and adopt new, efficient mining techniques. We could be developing the alternative energy generation and storage technologies that our country is so ideal for. Instead, we are forced to chase short term industry funding to keep ever dwindling research groups afloat.”

CSPU national secretary Nadine Flood said the damage had already been done with the loss of knowledge and expertise from CSIRO over the past two years.

It’s too soon to know how the innovation fund will work, but the focus on commercialisation could mean that many of the projects cut under the former Abbott government might not be replaced, if they do not meet the guidelines on research that can monetised. These include:

- Agriculture projects: animal biosecurity projects, including monitoring and testing for disease, and vaccine research for endemic livestock diseases;

- Environment projects: bush fire research, carbon accounting, climate modelling, sea-bed mapping, and atmospheric composition; and

- Health projects: colorectal cancer research, dementia research, and nutrition research into the benefits of cereals.

Projects the government would likely have been very interested in capitalising on, such as 3D-printing projects, big data projects, “internet of things” projects and data visualisation projects could be lost in the two years’ of budget cuts before Monday’s announcement.

Historically, CSIRO has often partnered with business and commercialised its research, with inventions like wi-fi, plastic banknotes and Aeroguard helping to contribute to ongoing research funding provided by successive governments, until the Abbott government. Now under Turnbull, however, the government is, to use one of the du jour start-up words, pivoting CSIRO’s focus from core research to a bigger focus on projects that can be commercialised. This is plain to see in yesterday’s announcement, alongside the appointment of former Telstra CEO David Thodey as the organisation’s chairman, and CEO Dr Larry Marshall, who holds 20 patents and has founded six US tech companies. Thodey, while taking lots of money from the government to get out of the fixed telecommunications network business, used that money to start up Telstra’s venture capital arm.

Turnbull didn’t seek to hide this shift for the company in his press conference yesterday:

“[CSIRO’s] new CEO, Larry Marshall, its new chairman, David Thodey, fresh from his transformational leadership at Telstra, are transforming the culture of this organisation, of the CSIRO so that it becomes, like a number of its counterparts in other countries, much more engaged with business. So that it is not only driving growth in Australia, but it is also ensuring that more Australians are imbued with its culture of imagination, of research, of invention.”

Similarly the $250 million, drawn from the Medical Research Super Fund, for a “biomedical translation fund” is designed to commercialise biomedical research. The projects that didn’t come with a commercialisation price tag sound like projects that would have been funded regardless of the government’s newfound interest in innovation. Funding for projects like the Australian Synchronotron ($520 million), the Centre fo Quantum Computation and Communications Technology ($26 million) and the Square-Kilometre Array ($294 million) will be widely welcomed by the scientists involved, but it is questionable as to whether these projects would not have continued to receive funding in the budget anyway.

The plans for machine-readable open data to be published by data.gov.au, and the small business portal for tendering for the government would have no doubt have been projects already in the planning stages by the Digital Transformation Office.

Pyne as education minister had been threatening to withhold funding for the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy if the Senate didn’t pass his higher education deregulation legislation. In his now-Walkley Award-winning interview on Sky News with David Speers, Pyne said he had “fixed it” in this year’s budget. Now that the NCRIS has been given $1.5 billion over 10 years, Pyne has said it is much more long-term and stable funding for the staff working on NCRIS, so he has now actually “fixed it”. But the funding for NCRIS starts from after the next election, so that fix depends on the election.

Start-ups and investors were the big winners. There were tax off-sets for investors ($106 million), new venture capital partnerships, changes to bankruptcy rules to allow businesses to keep trading and reducing the period from three years to 12 months, faster asset depreciation ($80 million), a new incubator support program, $36 million for “landing pads” in entrepreneurial hot spots like Tel Aviv and Silicon Valley.

Other announcements seem good in theory, but in practice still require much more detail. A total of $99 million has been set aside for teaching science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects, and $13 million in funding for women to get into STEM careers. Pushed on the funding, Turnbull told ABC’s 7.30 that it was about “raising awareness” and “mentoring”.

The big question remains: how will all this innovation be paid for? The answer probably lies in the Mid-Year Economic Fiscal Outlook due later this month. Until then, Pyne and Turnbull are on the road this week selling the agenda, with Pyne today addressing the National Press Club, and Turnbull speaking at an investment firm.

A heart transplant – for the one they took?

Sydney University ATAR BSc 83, anything with Law in it >99. How do career prospects and pay levels equate? Why would a really smart young person opt for a career in science?

How does this help an acknowledged lagging overall business culture? And, remember the big Australian film tax offsets for investors? Over many years they did not deal with key issues in that industry. Great for the investors though. Thanks for initial insights.

More investigation into this please Crikey. And we still have no tax regime so my suspicions are on higher alert. Tech innovation, sure, but who is making quality products? Innovation in management, production, where is that? And lets allow public servants to do their thing. Had government listened maybe insulation-gate would have been avoided. Checks and balances is good too. If failure is OK, as an enabler, so is fearless advice. Especially as we are talking public money. All things are linked so ….

“…Turnbull speaking at an investment firm.”

Where else?

Previous comment should be read ironically, not literally.