Government agencies need to learn to be innovative, agile and disruptive, according to our enthusiastic and optimistic Prime Minister, but what does that look like in the public service? Beanbags and table tennis tables.

This week, Malcolm Turnbull and Innovation Minister Christopher Pyne announced a $1.1 billion innovation agenda package, stating that government would be an “exemplar” in innovation through its investment in technology to deliver services. It’s still in the thought bubble stage as to how this will work in practice, but there are clues in a start-up-style project already underway at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

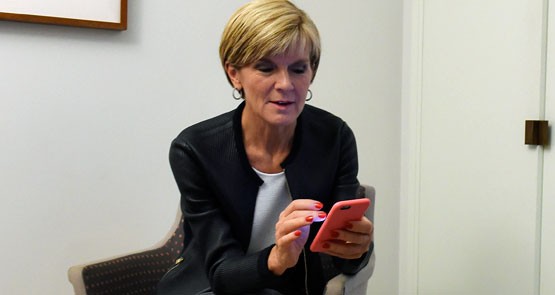

In March, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop launched “innovationXchange”, a $140 million, four-year project that is already being pushed as “Silicon Valley in Canberra“. It is the result of $11.3 billion cuts to foreign aid and the merger of Australia’s aid agencies. It is guided by an “international reference group” made up of philanthropists, Seven CEOs like Ryan Stokes, and the controversial climate sceptic Bjorn Lomborg.

It was an idea Bishop came up with in 2014, and, according to the department, the centre is “responsible for developing new partnerships to ensure our aid program takes advantage of new approaches and technologies to deliver better outcomes for development impact”. The staff “meet with innovators, private sector organisations and entrepreneurs who offer new approaches to aid delivery”.

Bishop herself has described innovationXchange as a “gorgeous little funky, hipster, Googly, Facebooky-type place”. When pushed, the department couldn’t explain what the Foreign Minister meant by this definition, outside of stating it was “a new way of working that encourages creativity and innovation”.

In the (perhaps) appropriately named Walter Turnbull building, innovationXchange has an open-plan office separate from the rest of DFAT, with reportedly nine staff, headed up by first assistant secretary Lisa Rauter. The fit-out is very different to what you would find in DFAT, as explained in documents recently tabled in response to questions on notice from the last round of Senate estimates hearings.

InnovationXchange bought three bean bags instead of a couch for staff to use. The bean bags cost $590 each, which the department claimed was “cheaper, more practical and adaptable than a three-seat couch”. Crikey, this morning looking at various bean bag couch options online, struggled to find one over the price of $300. The department would not respond to questions from Labor Senator Penny Wong on whether the bean bags met OH&S guidelines, except to say they conformed with Australian standards.

There is also a “large conference table” that has been converted to become a table tennis table for the department, just to complete the start-up look.

What ideas does this exciting new innovation hub come up with? Last year there were four programs run by the centre, a global innovation fund, a seed fund, the Bloomberg Data for Health program, and DFAT’s “Ideas Challenge”.

Currently innovationXChange has put a call out for “innovators, humanitarian experts, designers, scientists, and academics” to submit innovative ideas about Australia’s humanitarian response in the Pacific region, with $2 million on the table.

Some of the projects produced by innovationXchange include funding for East Timor to trial a new app to deliver nutrition messages. The centre gained attention last month when Fairfax reported, several months after Crikey‘s sister publication The Mandarin, that one of the ideas from the Ideas Challenge for a “cloud-based” passport to remove the need for Australians to carry their paper passports when travelling to New Zealand would be trialled.

The department also revealed that innovationXChange had held a meeting in October with Coca-Cola Amatil about how the program runs, at the same time as DFAT has held two meetings with the company regarding the potential for the company to help with aid distribution in Papua New Guinea.

Aid is a somewhat eyebrow-raising choice for the government to focus as part of its innovation agenda, but according to Rauter, “innovation diplomacy” can help governments deliver economic diplomacy:

“Innovation is fuelled by collaboration — taking an idea, sharing with others, using their knowledge and creativity to improve the idea, building on it, testing it, adapting and testing again. This collaborative process aligns very well with the intent behind diplomacy — the act of a state seeking to achieve its aims, in relation to those of others, through dialogue and negotiation.”

Unfortunately, Josh, what’s needed is a tad more expensive than bean bags. As with most institutions’ staff we first need to provide them with quality education, which entails first repairing our disastrous education systems, which can only be done after we’ve carried out tasks which between them make the Labours of Hercules look like a Sunday School Picnic.

I’ve suggested in the past that Crikey Land begin tackling the problem, but that’s probably an unfair request, isn’t it.

Good to see some recycled new names. The InnovationXchange was established by Grant Kearney back in about 2002 and closed in 2011. It was a well-known not-for-profit knowledge intermediary organisation in the Australian innovation policy space although the business model proved to be unsustainable… (for memory it was a spin out of AIG with some Commonwealth funding off the back of Howard Govt’s Backing Australia’s Ability innovation 2001 program)

Dont know if they had bean bags but variants were developed in UK and Malaysia.

Jaw dropping stuff. It’s like someone’s found a rejected script for “The Thick Of It”, and they actually think it’s a cunning plan.

When I was hungry, Jules gave me an app. I was thirsty and she gave me Coca-Cola.I was a stranger and she gave me a cloud-based passport.

I am captivated! Thinking, acting outside the square. Part, yet separate from, traditional DFAT. Each of the nine meeting and talking, explaining the Foreign Minister’s definition “a new way of working that encourages creativity and innovation”. A Project that is truly ‘Gorgeous, a little funky, hipster, Googly, Facebook-type place.’

Yes, I do jest, just a little . . but I do not decry value of embracing change, creativity and innovation. Thus I contribute for the Unit’s consideration as a resource . . read “D’Souza and Renner’s CMI winning book ‘Not Knowing’ – The Art of turning uncertainty into opportunity.

An excerpt . . “To admit to ignorance, uncertainty or ambivalence is to cede your place on the masthead, your slot on the programme, and allow all the coveted eyeballs to turn instead to the next hack who’s more than happy to sell them all the answers.” – Tim Kreider.