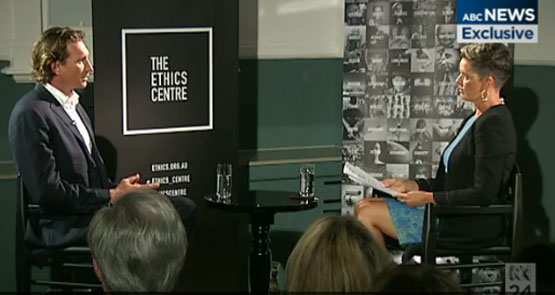

When he hit the stage at the Ethics Centre in Sydney last night, former Essendon coach James Hird looked extremely nervous. Thirty minutes late, facing an audience of only 60 people, he was sweaty and tense. But he soon warmed up — by the end of the interview, a soft chat with ABC reporter Tracey Holmes, full of Dorothy Dixers — he had visibly relaxed. Sadly, it was a missed opportunity; given the venue and the fact that this was an “exclusive” interview with the disgraced sportsman, I was expecting a much more nuanced discussion about morality and responsibilities. And, going by the vitriolic commentary on Twitter, so was much of the television audience.

Hird had obviously been told by his lawyer what he could say and resolutely stuck to the script. He repeatedly said that his main concern was the welfare of the 34 players who have been suspended for taking banned substances — that they were his close friends and he was very worried about them. A tougher interviewer might have ascertained whether some of this was due to reports that the players were about to sue the club for destroying their careers by involving them in illegalities. And with net assets of $37.3 million according to the last annual report, Essendon is a juicy target.

The former coach was fired by the club in 2015 following a string of investigations into illegal doping. Earlier this month, the international Court of Arbitration for Sport upheld the player ban, prompting the latest round of headlines. Last night, Hird said that “I have a level of responsibility in that. I should have known more. I should have done more when the opportunity came. I feel extremely guilty for that and bad for that. I can only apologise for that. I made decisions in real time that in hindsight, I think were wrong.”

He still says that he doesn’t know what was in the injections that the players received, but still believes it wasn’t illegal (which does sound like Alice in Wonderland.)

“At no time did I ever, ever consider that banned or performance-enhancing drugs would be at our club. It is just something that never entered my mind. I still to this date don’t believe that anything banned was given to our players.”

Later, in response to an audience question, he said, “why would I try and dope our players … there’s no rational reason for that.” He then said that “as the coach I don’t know and don’t want to know what the players are given … I don’t have the time to research it.” Later he said that he hasn’t read the World Anti-Doping Agency’s code of conduct in detail.

Although Hird had accepted full responsibility for the situation at a press conference in 2013, he now appears to be resiling from that, saying last night that he’d been “told to say those words”.

“I don’t think it’s fair for me to take full responsibility,” he said last night, adding that “at no stage” was he running the football club.

But if an internal investigation led by outsider Ziggy Switkowski, a former head of Telstra, can find that the club had operated a “pharmacologically experimental environment” then what was Hird doing — applying blinkers? He said last night that “I’m not a scientist or a doctor so I don’t want to go into areas of science that I don’t understand and it’s not my speciality, but the idea around the program was that it was a healthy program for the players to become better footballers and look after them later in life.”

This is where an interview conducted by Dr Simon Longstaff, the head of the Ethics Centre, would have been better. The history of corporate law is full of situations in which a company director or office-holder “knew or should have known” certain information — ignorance is no excuse. As the team coach, paid $1 million a year, shouldn’t Hird have known what the players were taking? After an audience question, he admitted that the injections were only given to the members of the “High-Performance Unit”, which excluded those players who were under 18 and those who didn’t want to take them.

The problem is that professional sport (for men) is just like horse and greyhound racing. The entire business model is built around a ready supply of young, fit creatures who are trained, “supplemented” and worked until they stop working, and then they are simply replaced with some more. (There’s not enough money in women’s sport to bother.) The 34 players involved in the Essendon scandal are learning what 99% of all former sportsmen know: you are only useful when you are playing and winning. And then it’s over.

For the Essendon fans, this has been a heartbreaking episode in the club’s long and illustrious history. But there is a much bigger issue — one of public trust in an Australian institution. Does the general populace still believe that they are watching a genuine sporting contest, or do they know that they are participating in a farce in which money and power trample all over the rules? If my 12-year-old son wanted to play AFL, would I entrust his health and wellbeing to a man who allowed players to be injected with substances he still isn’t sure about, who says that he “should have known more”? I don’t think so.

The constant focus on Hird has allowed every other party involved to avoid blame and scrutiny

Come on, this article is not up even close to scratch – it’s littered with inaccuracies (Hird’s lawyers had nothing to do with it; Hird does not represent the club therefore whether or not the players sue is a side issue and irrelevant to his motives; the ban wasn’t “upheld”, there wasn’t a “string” of investigations into player doping, to cite a few). A suggestion for writers on the Essendon affair: yes, there’s a goldmine of material, but get acquainted with the facts and nuances of the story, otherwise you will add nothing worth while.

PS; and a note for editors. If you have a Sydney writer offering a piece on this very Victorian affair, spike it.

Tracy Holmes comments in various places have indicated that she has missed the point. So has Hird. If you read the doping rules, they make it very clear that the responsibility is with the athlete. Hird’s 3 wise monkeys rubbish does not help them. The question remains, which Hird has not answered and probably will not be asked: what kind of coach becomes involved in a regime of injections when he does not know what they are (big no no in the rules). They were being given by a non medical person and were of great concern to the official doctor. This is what Hird will not address. It is like Lance Armstrong lite.

Mick Ellis I suggest you learn about the doping rules. The tricky strategy of Demetriou and the AFL to find no wrongdoing has exploded in their collective face. What Essendon, and James Hird were doing was a calamitous failure of duty of care. The administrators responsible should be removed at once. The penalty is hard on the players, but the final onus is on the competitor.