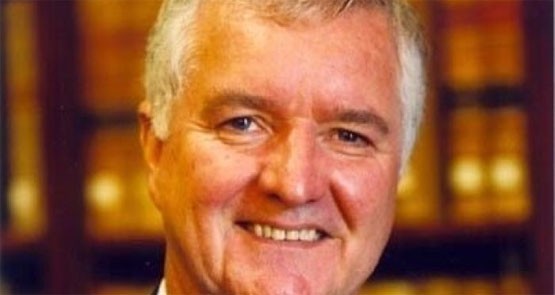

Kevin Duggan QC

Two former judges will secretly argue against government agencies trying to access the metadata of journalists to investigate leaks.

While alarm bells had been sounding on the government’s mandatory data retention legislation well before it was debated in Parliament, it was only just before the legislation passed that some in the media raised concerns about how the retention of call logs, email logs, location information and other telecommunications data for two years could impact on privacy — specifically the privacy of journalists and their sources.

Under the proposed scheme at that time, 22 agencies, including the Australian Federal Police, ASIO, and state-based police services that wanted to find the source for a story damaging to the government, could compel — without a warrant — Telstra, Optus, Vodafone or any of the telecommunications companies to hand over a journalist’s call logs to attempt to uncover the source of a story.

To make the scheme slightly more palatable to voters before the legislation ultimately passed, Labor proposed, and the Coalition accepted, a series of amendments to the mandatory data retention legislation that would require agencies to obtain a warrant if they wanted to access a journalist’s metadata for the purpose of investigating a leak. This isn’t an ordinary warrant process, however.

It will be conducted entirely in secret, with a “public interest advocate” appointed by the prime minister to argue on behalf of the journalist against releasing the data. This is all to be done without the journalist or his or her sources ever knowing that their metadata has been sought.

Telecommunications companies will also have no way of knowing when receiving a request for a journalist’s metadata whether the proper warrant process has been followed.

Documents released by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet under freedom of information last week — and first published by Fairfax — reveal Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull appointed his first public interest advocates in October last year, when the mandatory data retention scheme came into effect. The two part-time advocates, former Queensland Court of Appeal judge John Muir QC and former South Australian Supreme Court judge Kevin Duggan QC, will be appointed for five years.

Turnbull said in letters to both former judges that their former roles meant that they were not required to hold a security clearance before receiving any classified information they would be privy to in undertaking the public interest advocate role.

Muir is perhaps best known recently for being (one of) the Queensland justices to be highly critical of the former LNP government’s ill-fated appointment of Tim Carmody as chief justice of Queensland. According to his profile on Northbank Chambers’ website, Muir’s experience as a lawyer has mainly been in the area of company, mining, and commercial law, prior to being appointed as a judge in 1997. He has been the chairman of the Queensland Law Reform Commission and the president of the Land Appeal Court.

In a speech he gave to the North Queensland Bar Association Court of Appeal dinner in 2014, Muir spoke of the role of advocacy in the legal system, where he slammed Carmody’s appointment and made the case for the public to have confidence in the independence of the judiciary:

“Plainly, if public confidence in the independence of the judiciary is to be maintained, the judiciary must not be, or be seen to be, subject to direction or influence by the executive arm of government in matters which bear upon the determination of civil or criminal litigation. As it is often said, a significant role of the judiciary is to stand between the citizen and the state. Impartiality must be allied with independence.”

Duggan was appointed to the South Australian Supreme Court in 1988 and retired in 2011. He has since been recalled to fill in for the under-staffed courts temporarily, and has been called to a number of inquiries. In his time as a prosecutor, Duggan was said to have a “softly, softly, catchy monkey” style of cross-examination, and he appeared in “all the leading criminal cases of the day”. South Australian Bar Association president Mark Livesey described Duggan in 2011 as “one of the finest advocates before a jury this state has seen”:

“You had a great facility for not only persuading juries, but apparently recruiting them to the Crown’s thankless but necessary task of determining guilt.”

Unlike some other well-known former judges, Duggan also displays a kind of “wizardry with the computer and internet”, according to Livesey:

“Many of your associates remark on your facility with the computer and your determination to ensure that technology is used to its best advantage.”

Due to the highly secretive nature of the journalist warrant scheme, it is unknown yet whether Duggan and Muir have yet been called upon to defend journalists in the months since they were appointed. Late last year the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights suggested the scheme could be a breach of Australia’s human rights obligations because it could limit the right to effective remedy, right to a fair hearing, right to privacy and right to freedom of expression for journalists and their sources. The report said:

“The PIA scheme is established in such a way that the PIA cannot seek instruction from any person who may be affected by a warrant in any circumstance, including where it would have no impact on an ongoing investigation.”

The committee also stated that the PIA might not be able to mount an effective opposition to the warrant because all the PIA had to be given was a “summary” of the information provided to the minister or the agency seeking the warrant.

In any case, the warrant process can be bypassed by government agencies. A reverse search — where an agency gets all the metadata of people suspected of leaking to a journalist and finds out which one of those people has called a journalist — is one way around the scheme.

Last week the Attorney-General’s Department confirmed 61 agencies, including Australia Post, RSPCA Victoria, Bankstown City Council and the National Measurements Institute, had requested to be added to the list of agenices that can access metadata. No temporary access to any agency seeking it had been granted, but the department did not rule out potentially amending the legislation to add more agencies when Parliament resumes next month.

I suppose, Joshua, that items such as this help ‘justify’ your Crikey stipend, but have you no ambitions to write anything more?

Downright scary piece Josh.

I hadn’t realised the degree of pure Kalfka this legislation involved.

But then again, that’s part of it’s power & appeal to the spooks I guess. Winding it back to some form of public accountability seems unlikely under the current political leadership of either major party.

Quite depressing really.

The RSPCA and National Measurements Institute!

Really!!!!!!

Thanks Norman, have you no ambition to do anything but troll on the Crikey website?

Secret courts have no place in democratic jurisprudence.

To use a tekknikal term, “we is fukked!”.

Ken, the Crikey Commissariat has declined in the past, and will continue to do so in the future because I don’t meekly follow their Party Lines. As for our current “Mr Bigs”, they don’t engage in the simple crimes of their predecessors, but instead work within institutions in which they can benefit from legal rorts, so that it’s only where they want even more, and/or get greedy and/or are exposed after they squabble among themselves about their shares, etc., that the Law has any opportunity to act.

Action still requires individuals holding responsible positions in our Justice Systems to risk their prospects by speaking out, and that’s why (as has been shown in cases which did reach the light of day) the criminals have often come undone merely because they assumed it couldn’t happen to them.