The Productivity Commission has recommended wide-ranging changes to Australia’s copyright law to swing the balance back from a system that overwhelmingly favours vocal rights holders and is costing the Australian economy.

“The system has swung too far in favour of some vocal rights holders and some influential exporting IP nations, and it has lost sight of the users,” Productivity Commission commissioner Karen Chester told Crikey this morning following the release of the commission’s draft report on Australia’s intellectual property arrangements.

Australia is a net importer of IP, bringing in around $4.5 billion of intellectual property from overseas (mainly from the United States), while only exporting around $1 billion of our own. As a result, the Productivity Commission’s report found that over time, and largely through trade agreements such as the US free-trade agreement — which extended Australia’s copyright term to be life of the author plus 70 years — Australia’s copyright law has been expanded. But there was no overarching policy goal for intellectual property in Australia, no overall review of the system to see whether it was balanced, and no economic analysis of the impact these agreements would have on Australia.

“We were unable to identify what economic analysis underpinned Australia’s negotiating position there, and we had a lot of feedback from stakeholders who were frustrated that there wasn’t any meaningful consultation when those IP provisions were being negotiated,” Chester said.

The Productivity Commission has said the government should undertake a more comprehensive consideration of Australia’s interests and a standard model for IP agreements before undertaking any more trade negotiations.

The committee has found that the optimal copyright term would be 15 to 25 years after the creation of the content.

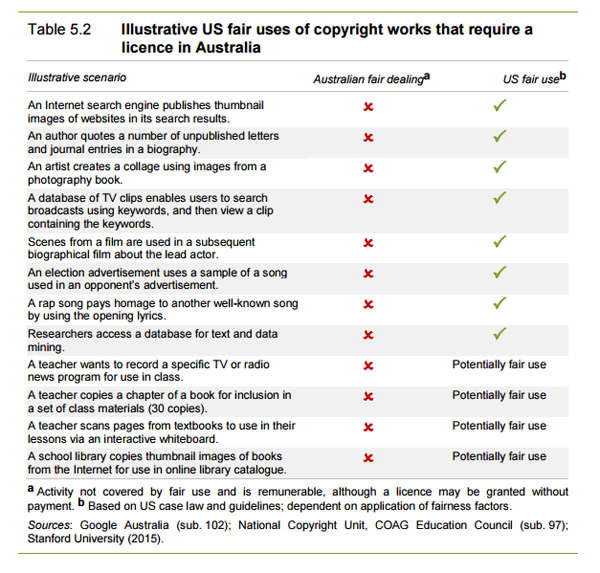

The report is likely to upset most vocal rights holder organisations in Australia, who have long campaigned against many of the changes the PC makes in its report. The Productivity Commission joins a long line of government agencies in recommending the government adopt a new fair-use standard, similar to that in the US, to replace fair dealing in the Copyright Act to make use of copyright works for adaptation, online services, news reporting, and in schools much easier. Unsurprisingly, this has been a strong sore point for many rights holders, which fear it would bring legal uncertainty for the right to protect their work. Chester said the Productivity Commission came to the view that legal uncertainty was not a compelling reason to abandon fair use.

“The fair deal exceptions in Australia aren’t a fair deal, and we think fair use, based on principles, would be a much better model to follow … they’d be adaptable to changes in technology over time and the way people access copyright material. Instead of being a positive list of what you can do … fair use is more principles that guide people in deciding whether they can use material without getting permission from the copyright holder.”

The Productivity Commission’s report savages every argument and analysis thrown up by rights holders to argue against bringing fair use into Australia’s copyright law. Chester says:

“It’s the classic Chicken Little — the sky is going to fall in if we move to fair use. We’re saying the analysis that has been done is wrong. Where it is alive and well in the US and Israel, innovation and creativity fosters, and from our perspective, it doesn’t really undermine the commercial rights of the actual rights holders themselves.”

Much of the focus in early media reports on the report has been on the PC’s recommendation, in line with that of the last IT pricing inquiry conducted by Parliament, that the Australian government not enter into international agreements that would ban Australians from dodging geoblocks put on services like Netflix to be able to access the same content as in the US. Chester said that lifting blocks would help reduce piracy in Australia.

“Online copyright infringement still remains a problem, and rights holders and their intermediaries say the solution is for penalties and for Big Brother intervention by law enforcement … the surveys say people would prefer to do the right thing but they will [infringe online] if they don’t have reasonable access, so geoblocking is still one of the primary methods which blocks reasonable access.”

Chester says the government should clarify in law that it is not illegal for an Australian to circumvent geoblocks.

This week Australia again topped the list of countries downloading the latest episode of Game of Thrones over peer-to-peer services despite the episode airing on Foxtel at the same time as the US. Foxtel’s price and the poor quality of the Foxtel Play app were some of the reasons people gave for continuing to torrent the show.

While no specific government ban exists today, Netflix has begun cracking down on VPN use at the behest of copyright owners as it tries to negotiate new global agreements that would let Netflix release third-party TV shows and movies to everyone across the world all at once, instead of needing to negotiate country-by-country for access to that content.

The report recommends an overhaul of the patents system to only allow patents for “truly inventive inventions”, whereas today around 40% of Australian patents are of very low value. Pharmaceutical patents extensions were ineffective in promoting research and development, the commission found, which cost taxpayers $500 million per year. The commission recommended these extensions should only be granted where there is an unreasonable delay in getting TGA approval.

Chester admits that Australia is limited in the changes it can make due to the international trade agreements we have entered into, but said all the recommendations in the draft report can be made without putting Australia in breach of its obligations.

“We’ve worked out where there is policy wiggle room within our current obligations, and it is still meaningful reform. They’re workable, and they will make material difference to consumers, schools, follow-on innovators, and follow-on creators.”

One of the major criticisms of Australia recently signing the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement was that the government declined to refer the agreement to the Productivity Commission to review. Chester said that the PC didn’t mind who did the analysis of the agreements, just so long as there was proper analysis done.

“It’s how you inject that discipline into the negotiations. There should be some areas that there are no-go zones. When the analysis is done, and Canberra knows the impact it can have on a budget, all of sudden you get a line in the sand drawn as part of those negotiations.”

The final report is due to government in August.

Attorney-General George Brandis — who, it should be noted, is no longer responsible for copyright law — has previously indicated a reluctance to pursue fair use. While some in Labor, such as Ed Husic, have cheered on the recommendations of the report, Labor shadow attorney-general Mark Dreyfus told Crikey in a statement that the party welcomed updating copyright law, but that Labor would examine the findings and await the final report.

“Chester admits that Australia is limited in the changes it can make due to the international trade agreements we have entered into.”

Who would have guessed, other than the thousands of people who said these fair trade deals were neither fair, nor enhanced trade. Selling our souls for a hill of beans.

Although it could equally be argued that our copyright laws have been written by US corporations whether there’s a fair trade deal or not. Mickey Mouse anyone?

They will have to rip this VPN from my cold dead mouse.

When they actually price a service at something *vaguely* approximating what it’s worth…Then I’ll happily pay them for the product.

It’s not rocket science and the early adopters will reap the benefits.

I write books. You’re telling me that I have only 15-25 years to make a profit from each book, before it becomes open slather and anyone else can use my novels as a basis for their money-making ventures?

Thanks for making all writers and artists feel even more devalued.

I buy a book and it’s mine. I can sell it, lend it, give it away, carry it anywhere in the world.

Yet I have boxes and boxes of DVDs that friends have bought in England and sent me here in Australia and they are geoblocked. I can’t play them.

How is geoblocking anything other than theft?