It was apposite that on budget night, when the latest in Australia’s growing conga line of barely numerate treasurers ratcheted up the government forecast for iron ore by a stonking US$16 per tonne to US$55 per tonne, that the price of the red dirt fell 4.1%, back towards US$60 per tonne.

The sharp dip in what has been a very volatile iron ore price these past three months came hours after the Australian dollar dropped 1.5c to close near 75 US cents on the back of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s cut to the lowest interest rates ever seen in this country.

As has been typical of its performance in the past decade or so, Australian Treasury, largely cosseted in Canberra, continues to get the global economy wrong. And with it, the important numbers — such as the iron ore price and the value of the Australian dollar — that make a well-forecasted budget.

So far this calendar year, the average price of iron ore is just US$51.20 per tonne, and for the past 12 months it’s US$53 per tonne. The unexpectedly strong recent rally has been driven as much by financial speculators as a (small) uptick in demand. So Treasury is betting that the iron ore price will have another sustained rally, in an environment where the price cyclically, for the year, has probably peaked, and structurally, the industry — led by Rio Tinto and Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting — is producing more ore in an environment of demand, which is, at very best, edging up far less quickly. That, folks, is innumerate, and most analysts have a 2016 average price of between US$35 to US$45 per tonne.

Last year’s budget for 2015-16, which was very bullish on China, was no exception.

It was clear that under China’s rubbery headline GDP numbers there was a set of serious problems emerging. Yet, to use a phrase that former Australian ambassador to Beijing Geoff Raby liked to use, Treasury continued to take a Pollyanna approach to China.

Instead what we have seen, as of May 2, 2016, is now 14 consecutive months of the official government Purchasing Managers Index, a closely watched guide of manufacturing activity, showing a continuing contracting in activity. More alarmingly, China’s levels of debt have continued to rise ever further, boosted in recent months by yet another bout of economic stimulus that has had little effect on growth figures.

“Looking forward, solid and sustained growth in China will be underpinned by the transition to a pattern of growth that is more reliant on consumption,” last year’s budget forecast.

But none of this has happened. There has been precisely nil institutional reform, and the nation’s leaders are now widely seen by the global economist community as having all but lost control of the country’s economic trajectory.

Even in the Mid Year Fiscal and Economic Outlook (MYEFO) there was a remarkable lack of insight from people with masters and PhDs in economics up the wazoo:

“While emerging market economies have slowed in 2015, their growth is expected to pick up in 2016 and 2017. More than 70 per cent of world growth is expected to come from emerging market economies, predominantly those within the Asia‑Pacific region.”

What a dreadful collective waste of money and time at university, as since then, well, things have only deteriorated and the global “R” word — recession — is now bandied about with some seriousness. Crikey, at least, understood this at the time, but what would we know?

Still, there was no dodging that this commentary, made juts five month back, was a big “oops” so Morrison took the hit “expectations for global growth are lower than at the 2015-16 MYEFO and the global environment remains uncertain, providing risks to the forecasts of Australia’s economic growth.”

Still, the geniuses at Treasury appears to have finally woken up and smelled the coffee on China, even if they haven’t quite forced it down yet. (No, folks, niche farm and seafood products, tourism and international students will not, ever, fill the mining gap.) Says yesterday’s budget papers:

“China’s economic transition is expected to contribute to more sustainable growth over the longer term. But in the near to medium term, increasing consumption and rising service sectors are unlikely to fully offset the decline in investment and a slowing industrial sector. The key risks to China’s transition are its current industrial overcapacity and domestic debt challenges. Effectively managing these risks will be important in ensuring a smooth rebalancing of the economy.”

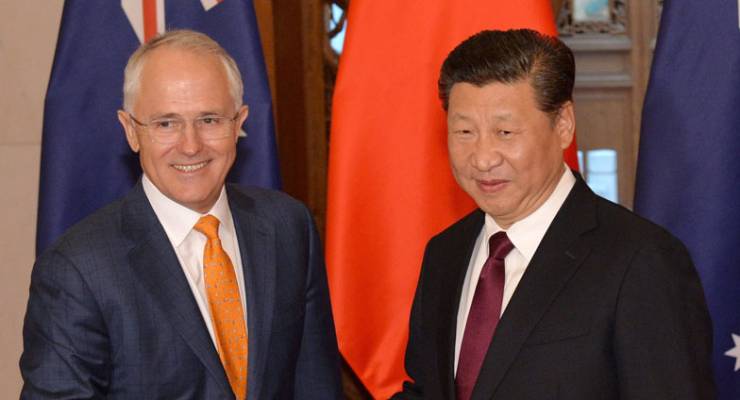

So far, not so well-managed in Beijing, but at least least there is no longer unbridled confidence in the Chinese economic transition. Still, that was about it, and there was precious little talk about the international economic environment in Morrison’s main budget speech, yet this was the key environment invoked by the RBA in its rate cut.

In a world where China’s economy will continue to be problematic, affecting the rest of Asia, Japan is permanently flat-lining and commodities are in a multi-year existential funk of over-supply, Australia is somehow going to double its growth rate in three years on the back of more tourists and better lobster and cherry sales to China? It doesn’t even really fit with Treasury’s own comments deeper in the budget papers. So good luck with that.

Apart from his egregious foray to Cambodia for Australia’s reprehensible, expensive and abjectly failed refugee resettlement deal and trips to Indonesia for “border protection” he has very limited experience in Asia, or indeed the rest of the world. It’s a long time since he ran Tourism Australia, and I don’t think he acquitted himself so well there, either.

It is not only Treasury people who wilfully misunderstand China. That also applies to most commentators who either overlook or misunderstand the profound changes that are taking place in Eurasia at present, of which China’s One Belt, One Road policies (the world’s largest infrastructure project) are a central component. This is despite the relentless attempts at sabotage led by the usual suspects, and in which Australia is at the very least a complicit player.

The One Belt, One Road projects have at their heart the transformation of China’s access to resources across Eurasia. That access will be untrammelled by US warships in the South China Sea. Among the resources accessed by high speed rail are precisely the resources that Australia has grown rich on supplying China over the past few decades. A far greater problem for Australian producers of iron ore, coal, natural gas etc than the price will be whether the Chinese will continue to buy from us at all. Put yourself in their position. Given a choice between reliable, easily accessed resources from land based neighbours, and importing from a country whose so-called Defence policy is based on barely disguised belligerence to our largest trading parter by far, for and on behalf of the Americans, which source would you choose?

The reality of that choice is very close, and we continue to ignore it at our peril.

Don’t those land-based neighbours also harbour a certain belligerance towards China?

Woopwoop, China has a shared border with 14 countries. I am not sure what you mean by “belligerence” toward China. The only extant border dispute is with India which is being worked out amicably between the two countries. There have been historical disputes, for example, with Vietnam and Russia, but again they have been resolved. Those neighbours are much more conscious of the benefits that can accrue from good relations and when there is no outside interference (which there currently is on a large scale) things are generally sorted out.

The western media would have you believe that there is tension, but will never talk about their role in promoting that tension. Just as the Australian media is reluctant to talk about the tension we create with our neighbours; eg. the bullying of East Timor.

They still need the West to buy all the trinkets & gee-gaws produced in the world’s workshop – if we down at the arse end of the world haven’t the cash coz they stopped buying our resources that would be an interesting inversion of the tea/silver & opium problem which Old Blighty solved with the cry in Westminster to “send a gunboat up the river!”