To mangle Paul Keating’s famous phrase, never get between business leaders and a bucket of money.

Both business and the Coalition have upped their already extraordinary rhetoric about the Coalition’s proposed tax cut for big companies. Today in the Financial Review, the executives responsible for the biggest business lobby groups — the Business Council of Australia, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Australian Industry Group and the Minerals Council of Australia — launched a broadside at opposition to the tax cut. With an accompanying piece of cheerleading from Tory columnist Jennifer Hewett, the Four Rentseekers insisted that Treasury’s modelling of the benefits was sound, that critics were guilty of basic maths errors, that the UK showed that cutting company taxes stimulated investment, and that opponents needed to come up with an alternative proposal.

Business weren’t the only ones upping the hype. Yesterday Arthur “I don’t recall” Sinodinos accused Labor of “sovereign risk” in opposing the tax cut. The Coalition — and business — famously redefined “sovereign risk” during the mining tax debate to mean “anything we don’t like”, but Sinodinos, to his credit, found a new way to mangle the meaning of the term, applying a concept originally intended to denote uncertainty created by regulatory change to retaining existing regulatory arrangements. Perhaps Arthur had had yet another memory lapse and forgot what it actually meant. Remember, all of this “war on business” stuff isn’t about imposing a new tax on business, but failing to deliver a truly massive tax cut to big business.

The Four Rentseekers’ attack, however, was riddled with much worse errors than Artie’s jibe. “Today our economy is struggling through a difficult transition,” they aver, ignoring that the March quarter GDP result showed the economy growing at over 3%. Of course, they would ignore that, since it was powered by a strong export performance generated by the massive mining investment boom that occurred while Labor was in office and the company tax rate was 30%. “Productivity growth is weak,” they insist, ignoring the strong growth in labour productivity that has occurred over recent years under Labor’s Fair Work Act, far higher than under WorkChoices. They claim, in an admittedly rare example of company tax cut advocates trying to use real-world evidence, that “we also know that the Britain [sic] have cut their rate from 28 per cent to 20 per cent since 2010 among a range of reforms and they appear to be reaping the rewards” — except as Crikey has shown, Britain has underperformed Australia on most crucial indicators (especially productivity) in recent years. They also say that Australia’s “budgetary position” is a “challenge”, before going on to explain why $50 billion should be hacked out of revenue over the coming decade. They insist “the criticisms levelled at proposed tax reforms do not seriously challenge the potential gains to be had,” except that, even if this claim is accepted, the “potential gains” are by the government’s own admission minuscule in terms of additional growth and employment.

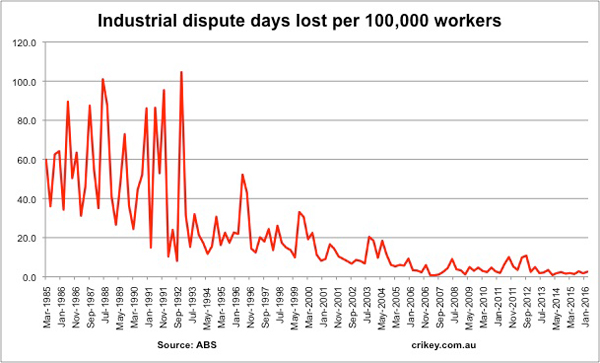

Most peculiar is the Four Rentseekers’ insistence that “some of the discussion about business this election seems to assume that the business sector is somehow separate from the broader community”. Problem is, it’s the business community that behaves as if it’s separate. The other week in a Press Club debate, one of the Rentseekers, James Pearson of ACCI, attacked the union movement for no longer co-operating with business as it did in the 1980s and having an “us and them” attitude — despite the extraordinary fall in industrial disputes since the 1980s that Pearson was rhapsodising about.

And it’s the business community that wants to cut penalty rates for the lowest-paid workers in the country, wants a GST increase to pay for a company tax cut and deplores any efforts to end rampant multinational tax avoidance — all positions strongly opposed by the electorate, which is united across party lines in despising multinational tax avoidance, cutting penalty rates and GST increases. When you adopt self-interested positions that directly conflict with the views of the majority of the electorate, you don’t then get to complain to you’re being treated as separate from the community.

And then there’s the Rentseekers’ conclusion, that critics have failed to produce an alternative policy to a giant tax cut for big business. Well, how about a company tax system under which Australia experienced a massive foreign investment surge that powered the economy while the rest of the world struggled in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and which is now powering the economy such that we’re about the only developed economy growing at the same pace as the global economy? Not to mention an industrial relations system that has enabled the flexibility for workers to trade off wage rises for higher employment — something the RBA, the Productivity Commission and even ACCI itself acknowledge?

Of course, there are problems with the current company tax regime in Australia. Everyone knows that. The biggest problem is tax avoidance by big companies. Even the Coalition has had to acknowledge that. Strangely, the Four Rentseekers don’t mention the billions lost in profit-shifting, transfer pricing, overpriced loans or other rorts by their members even once in their long screed.

Not “separate from the broader community”, eh?

I am not an economist but I like to think I understand mathematics. I am puzzled by “the only developed economy growing at the same pace as the global economy” as in effect the growth of the global community is the moneyweighted average of the individual economies. Thus if we are average there are many above and many below us. If we are the only “developed economy” then those below us must be the developed economies, and those above us must be “non-developed”. I would expect the latter to have very much smaller economies than the former, and hence I have extreme difficulty in accepting the statement. Perhaps I just don’t understand. To quote a former Queensland parliamentarion and perhaps soon to be a senator, please explain.

Less developed countries tend to grow faster as they have large under-used work forces, less advanced technology and under-exploited resources. Thus even a modest investment can produce a large result.

Australia has been supported by the China bubble and so has not shown most of the signs of sclerotic developed economies.

There are a lot more of the developing economies than they are of teh developed economies.

And, I believe, China is not considered among the developed economies.

And “developed economies” is probably referring to those which are members of the OECD, which includes countries like Australia, the US and Japan, but not China.

I am waiting for the LNP to explain how multi-nationals that pay very little tax will invest more when their tax rate is cut.

Effectively they already have a very low tax rate. Where is the investment that should have followed?

I think that the tax cuts should be offered in exchange for guaranteed increases in investment and employment.

Those large companies that increase those by an equivalent amount to the tax cuts (ie 16.7%) can get the tax cut, but those who do not stay at the 30% rate.

Nice Bernard..

Great article.

Michael Hudson’s “Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy” describes in detail the shift to reduce the tax on finance and real estate and global companies. The burden of tax is shifted to labour and consumers with cuts in public infrastructure and social spending. We have put the rentier managers in charge of government. It happens because the host (the productive economy) has been anaesthetised and does not recognise the extraction of the life blood of money from the productive economy.