It’s been a while since a serious security issue raised its troublesome head during an election campaign. And I mean serious, not the spectre of an “invasion” of desperate refugees on rickety boats, raised by desperate politicians (Malcolm Turnbull, please take a bow)

But there is every chance that sometime during the next six days a relatively obscure court in The Hague could light a fire under the bubbling regional security issues of China’s increasingly aggressive and, most lawyers argue, illegal behaviour in the South China Sea.

Such a fundamental issue of broad regional security is unprecedented in post-Vietnam War politics. China in in dispute with, in alphabetical order, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam.

China has consistently insisted that all negotiations in the South China Sea be conducted bilaterally. This is at the same time that is also insists that it be included and taken seriously in other global multilateral forums. It is very excited — beside itself, actually — that it is hosting the G20 economic forum this year, and blow-by-blow preparations for the event are being reported breathlessly in state-run media. (Despite being the world’s second-largest economy, it is still yet to be included in the old-world G7, initially the world’s club of its largest economies but now very much the “Western Economic Club”).

Only one country has been brave enough to officially challenge China: the Philippines has taken its dispute to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.

China is, simultaneously, Australia’s major and most important trading partner, and the region’s wannabe hegemon and major potential regional security threat; Chinese leader Xi Jinping has promised the first stage of the country’s accelerating military upgrade by 2020 — now barely four years away.

Politically, security is usually manna for the conservative side of politics, but given that the issue is with China, it’s a very delicate dance.

Labor, or at least its defence spokesman Stephen Conroy — never one to be backwards in coming forwards — came out of the blocks fighting with tough talk on a response to China’s artificial islands in the South China Sea, promising Australian forces would do this, that and the the other thing.

Opposition foreign affairs spokeswoman Tanya Plibersek has been more tempered; promising a Labor government would work with security and intelligence advisers and saying it was important not to talk these things up in a way that contributed to tensions. A rebuke to her Senate colleague? Good luck with that.

From the government’s point of view, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop this week mouthed the usual platitudes that Australia did not want to add to tensions in the region. What no one is quite game to say in Australia is is what the Philippines, Vietnam and now Indonesia are: that China is the only country that is actually adding to those tensions.

By claiming virtually all of the South China Sea as a “Chinese lake”, as defence analysts put it, the country is ratcheting up regional security by building its own islands with airstrips, defence systems and an unknown number of troops.

A recent poll by the Lowy Institute showed that 74% of Australians were in favour of our defence forces conducting freedom-of-navigation operations in the South China Sea.

Australia has made it clear it doesn’t recognise China’s territorial claims and if the Permanent Court of Arbitration concurs, we have placed ourselves clearly on the non-China side.

“It will do [China] irreparable harm to its reputation if it thumbs its nose at the findings of the arbitration court and we have urged all parties to abide by the findings of the court,” Bishop has said. While the court won’t adjudicate on the actual boundaries, many observers believe that it could dismiss the famous nine-dash line — which China has unilaterally drawn on maps to claim this vast expanse of ocean — as officially redundant.

[China as repressive as ever, but Australia lacks Hawke’s moral fibre]

The trouble could come if China decides to start its island building games on the Scarborough Shoal, the chain of rocket islets in disputes with the Philippines. The commentary from the US has become distinctly bellicose in recent weeks.

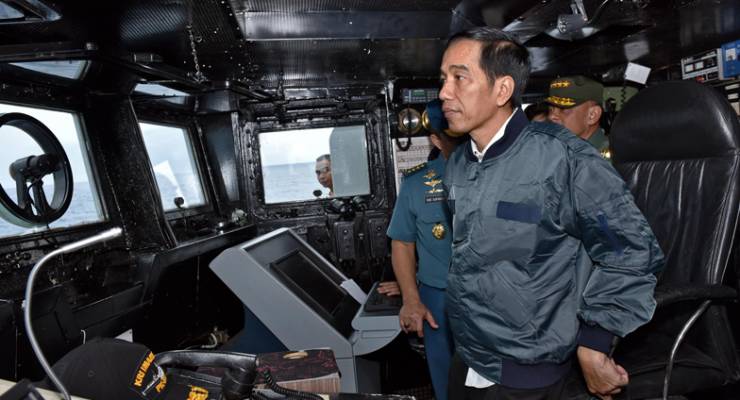

Last week, Indonesia — a country long reticent to take the fight to the Chinese — finally stood up, with President Joko Widodo visiting Indonesia’s remote Natuna Islands, located in the South China Sea, in a warship as an apparent show of force to Beijing.

Through its aggression, China has managed the remarkable feat of turning nations like Vietnam and Indonesia towards the US and driving wavering allies such as Japan and the Philippines back towards its protector. If observers were uncertain about Barack Obama’s pivot to Asia, there is now little doubt about its seriousness. China has made sure of that. Australia, for its part at least, has stronger regional allies than it did five year ago; the country is far closer to Japan and the Philippines militarily; toes are ever warming with Vietnam; and Australia recently inked an unprecedented $2 billion strategic deal with Singapore, the cashed-up fulcrum of south-east Asia.

Any moves by the UN court in the next week will liven up this dreary election but perhaps not in the way that anyone would want.

Whatever happens, it’s unlikely that, if returned as PM, Malcolm Turnbull will let his predecessor Tony Abbott anywhere near the defence portfolio, a move Abbott continues to fly the kite on through News Corp outlets.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.