From before the dawn tomorrow morning to shortly before midnight, 75,000 AEC staff will wrangle the logistics and the rules of Australia’s democracy.

They’ll be joined by thousands of volunteers, who will spend hours handing out how-to-vote cards for the parties and possibly scrutineering the count at the polling booth well into the night.

The system of how people’s votes are actually counted is a complex one, but some things stay the same no matter what the specifics of the polling booth. Crikey spoke to AEC staff past and present, as well as veteran scrutineers, to find out what happens when the polls close at 6pm.

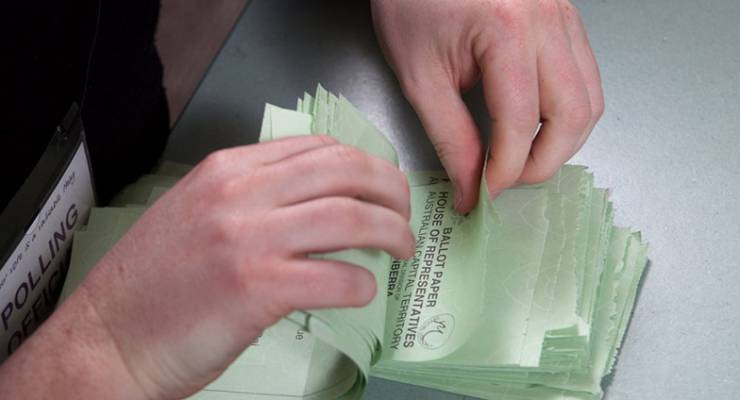

Counting begins almost immediately; the doors close as soon as the last voter is out. Counting is done on a booth by booth level to minimise the risk of interference with ballots and to save time. The first thing that’s done is the ballot boxes are inspected to make sure the seals are still holding, in full and easy view of the scrutineers (volunteers or party staffers nominated by the candidates to check the count is above board).

Then, the votes are released.

“Typically what happens is the votes are in one giant pile,” said one former AEC staffer. “Once you flatten them out so you can see them easily, you start dividing them up. You grab a clump and start distributing them into their first preferences.” Ballots not completed correctly, or informal votes, are put into their own pile. Totals are determined for each pile, and the results are called in to the divisional returning officer and entered into the Tally Room website, run by the AEC.

The website has a media portal, so the press can keep an eye on these results right from the start. That’s a fairly new development — there was a time when the parties relied on scrutineers to keep information flowing, but often the information is most quickly available through the Tally Room website these days.

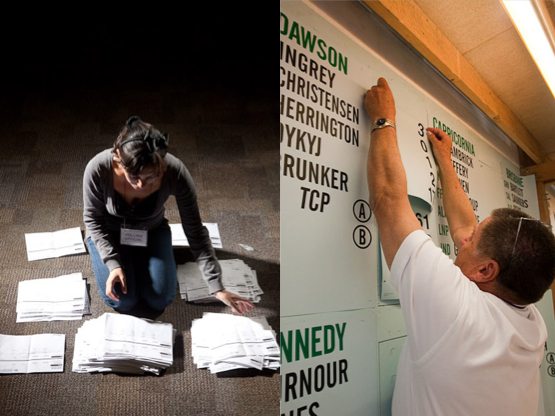

Polling officials will have a feel for who are likely to be the two leading candidates in their booths once the preferences are counted. So after first preferences are done, the papers are distributed again into two piles: one for each of these candidates, depending on who is higher on the ballot paper. If there’s an upset (a Greens candidate unexpectedly polls far better than the Liberal and Labor candidates, for example), this can always be done again.

There’s a fair bit of recounting that goes on at election night. Booth officials know how many people have voted in their booth overall (anywhere between a few hundred to one or two thousand if it’s a major booth), and they keep an eye on the total number of papers they have, including informals, to make sure no votes are missed. If the numbers are out, they do it again. One polling official told Crikey in past elections, they’ve been allowed to be out by one vote. Counting machines have made appearances at some state elections in recent years, but the process is still mostly done by hand.

The scrutineers aren’t allowed to touch the ballots, but they can get in pretty close. How close will often depend on the set-up of the counting room. If it’s in a school, the AEC staff will count on tables and scrutineers can watch from the other side. If it’s a hall, counting is often done along the side, which means scrutineers have to peer over people’s shoulders to see the ballots.

How seriously they take the role varies. Some take the attitude that if someone wanted to vote a certain way the vote should generally stand even if it hasn’t been filled out right, while others are sticklers, paying close attention to the piles of the rival candidates in a bid to get ballots disqualified. If a ballot hasn’t been correctly filled out, the scrutineer can flag it, and the returning officer will come over and make a ruling.

It’s usually fairly above board, the scrutineers we spoke to said. The parties don’t expect the scrutineers to be too tribal about it — they’re told to follow the rules and not make things hard for the AEC. In safe seats, there can be a pretty friendly atmosphere — the result is a foregone conclusion, so why make enemies? Though it very much depends on the scrutineers themselves and how they see their role. In an upset, it can get pretty tense.

[Poll Bludger: the seats to watch at your election party, as they come in]

Booths within an electorate can vary widely in terms of election result. This means it can be hard for booth officials and the scrutineers to gauge how the candidates are doing throughout the rest of the electorate. “When there’s a big swing on and you’re watching it happen, it can be pretty scary, or exciting, depending on what side of it you’re on,” a major party scrutineer said. Those in the counting rooms get a first taste of the numbers, but they’re far more incomplete than what viewers at home are used to. Until later in the night, no one’s sure what they mean.

Things in the Senate are even more vague. Once the lower house is done, the officials move onto the Senate voting papers. The method is, again, to pile them according to first preferences. But because of the sheer number of candidates and preference allocations going on, it doesn’t go any further than that on the night.

[Poll Bludger: what the Senate will look like after the election]

Most people vote above the line, with a “1” next to the party of their choice — which makes it pretty easy for AEC staff. Below-the-line votes can be much harder to deal with at the end of a long night. AEC staff scan the ballots for the “1”, but with hundreds of boxes on the paper, former staffers say plenty of ballots end up in the informal pile for someone not quickly finding the first preference (this doesn’t mean the vote lapses — such ballots are counted more than once, but not election night). But if many voters only number 12 boxes below the line this time, it may be far easier to deal with.

Once total first-preference votes for each booth are figured out, they’re called into the divisional returning officer, who puts the result onto the Tally Room site. By this point, it’s anywhere from 8.30pm to midnight, and the conclusion of a massive day for all involved.

The Senate papers will be counted in the three weeks following the election. This year for the first time, the AEC has automatic scanners to do it. This has largely been implemented because of the changes to Senate voting that allow a minimum of six preferences above the line and a minimum of 12 below the line.

Fuji Xerox won a $17 million contract earlier this year, and according to documentation seen by Crikey, the system uses optical character recognition to determine the preferences on each of the millions of ballot papers, and this is then verified by a person — to ensure what was scanned matches how the person actually voted.

[Why do we vote like it’s 1999?]

Also counted after election night are postal votes (which the AEC can receive up to 13 days after election day — they must be filed before election day, but the AEC allows for delivery time) those made by voters outside their electorate.

The training given to AEC staff varies. This election, the grunts have been sent an A4 booklet a few dozen pages long and been told to turn up to a polling booth at 6.50am on the day. But the AEC tries to have one or two people at every booth who have more training and experience. The higher up booth officials have had three hours of paid training.

Last election, 1300 Senate votes were lost in WA after election night, forcing voters across the state to vote again when they could not be found. Crikey asked the AEC what, if anything, had been done to prevent this happening again. “The AEC has progressively trialled a number of these changes at the electoral events since the last election. The changes are numerous but are largely focused on enhanced electoral integrity and ballot paper security — enhanced tracking and accounting for ballot papers from the time they are printed to the polling place to the count centres and ultimately to secure storage following the election,” a spokesman said.

The AEC is very keen to avoid an embarrassing repeat. This time, booth staff have been given significant training on secure handling of ballots, and rules about where ballots can be kept. The boxes for declaration votes — that is, votes where people are not in the electorate, or can’t be found on the electoral roll — are not opened at the polling place and are sent off to a centre where they are kept under lock and key until they are opened and reconciled with the electorate that person should have voted in.

AEC staff we spoke to were fairly positive about the experience. They’re well paid, generally fed on the night (though last election we spoke to some staff who said they didn’t get a break for dinner), and appreciate the part they play. Though those doing it for the first time can feel thrown in the deep end — not everyone gets a training session, after all.

A lack of training is probably the biggest quibble with the system, though the AEC can only stretch its budget so far. AEC staff are not allowed to be politically active. Booth workers are usually uni students or retirees, though we’ve heard tales of a bank teller doing the job. “She was phenomenal — so quick,” said one AEC staffer.

As for the scrutineers? Their days are often similarly long and come with no pay, but for the political die-hards they can be fun.

“You get up early, spend the day wrangling the votes, and then, it’s your chance to see how you did at the end of the day,” a former scrutineer told Crikey. “It’s part of the sport — you see how your booth has done.”

Another long-suffering party scrutineering veteran vehemently disagreed.

“The important thing you’ve got to say about scrutineers is how awful it is for them when everyone else is at the party. It’s the bane of everyone’s existence. It’s usually the people who are most experienced doing it — so those who have worked the hardest during the campaign. They’re the ones who most deserve a drink!”

Additional reporting by Josh Taylor

We need electronic voting now, to stop people voting more than once and to have results within an hour, including the Senate with preferences, so that all that changes is postal votes.

Not fully electronic voting please, as in some US states; too vulnerable to fraud and/or breakdowns.

How about a hybrid system – voters push buttons on a voting machine to generate a formal vote, the machine prints a paper voting card, the voter checks the card and puts it in the box.

The electronic totals can be announced on the night, but later the cards are all optically scanned and that’s what finally counts.

In case of computer breakdown at a booth, revert back to a paper system.

StefanL – Excellent idea, I’d not thought of that.

Interesting article, thanks.

Since the introduction of two-party counts at the polling place, the scrutineer’s role is largely redundant. Older political junkies will recall Robert Ray for example usually being well ahead of other television panelists because he had the magic of two-party preferred information at selected booths and the comparison with the previous election gave him confidence about his predictions of seat outcomes. However, this depended on the skill of individual scrutineers. Watching a batch of 50 ballot papers and identifying whether each preferred Liberal to Labor was a task beyond many, so the report to campaign HQ would say something like the Democrats preferences went about 50-50, which might turn out to be anything from 35-65 to 70-30 on closer examination.

Now the role of scrutineer is largely to record and report the primary votes and the preliminary 2PP, which barely beats the figures being posted online by the AEC.

As for objecting to the formality of votes, this is a mug’s game, if done cynically. It just annoys the staff as the end of their perhaps 14-15 hour day is approaching, to no good purpose.

Typically the counting staff will refer any possible informal to their senior staffer and s/he will usually ask scrutineers from both (all) sides for their assessment.

If it ever comes down to a situation where every vote is contested there will be at least a re-check, and in rare instances a full recount (with more skilled scrutineers in attendance). I have sat in on three such recounts, final margin 87 in one case and low four figures in the others.