It’s taken more than a week, but clarity has finally emerged from the confusion that prevailed after last weekend’s finely balanced federal election.

Bill Shorten felt obliged to concede yesterday after three crossbenchers effectively declared their hands for the Coalition, but the late progress of the count had made it increasingly likely that their support would not be needed in any case.

Coalition candidates now lead in 76 out of 150 seats, and they are at least an even chance of making it to 77 when the outstanding votes are tallied in the Townsville-based seat of Herbert.

A majority of any size is sufficient to secure full control over the executive branch of government, and the Coalition looks to have achieved this one from barely more than 42% of the primary vote.

This is, to be sure, slightly more than Bob Hawke and John Howard could manage when they respectively won narrow majorities at elections in 1990 and 1998, when voters abandoned the major parties for the Australian Democrats and One Nation.

On those occasions, it was more or less back to business as usual when the next elections followed in 1993 and 2001. The current rebellion has a greater feeling of permanence about it, with the non-major party vote now having increased over three consecutive elections.

With the two major parties barely able to claim three-quarters of the vote between them, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for governments to argue they have a mandate worthy of the name, purely on account of artificial majorities delivered by a distorted electoral system.

So it’s important to acknowledge the success of the Turnbull government’s electoral reforms in delivering a Senate that is, in stark contrast to the House, every bit as shapeless and unmanageable as the electorate it represents.

The Coalition parties have no guarantee of exceeding 30 seats in the new Senate, compared with 33 before the election, and the crossbench they face will likely consist of seven to nine Greens; three each for the parties of Pauline Hanson and Nick Xenophon; Derryn Hinch from Victoria; Jacqui Lambie from Tasmania; and potentially Liberal Democrats from Queensland as well as New South Wales.

The blame for Hanson’s resurrection lies at least in part with Turnbull’s double dissolution strategy, but she might have been looking at one seat rather than three if the old electoral system had been left in place.

Some of the responsibility for that rests with the Greens, who combined with the government to pass the legislation in March in the face of opposition from Labor.

At that time, the Greens plotted a course that combined self-interest with a high-minded concern to curtail the power of party machines over voters’ preferences.

They may be feeling less sanguine now about the abandonment of a group voting ticket system that, for all its flaws, gave the establishment parties an effective means to collude against incursions from the far right.

But it’s not all bad news on the Senate reform front, with one result set to gladden the heart of any election watcher not directly implicated in the factional machinations of the two major parties.

In sorting out the order of their Senate tickets for the double dissolution election, both Labor and Liberal in Tasmania went to objectionable lengths in prioritising factional and ideological considerations.

Labor relegated incumbent Lisa Singh to the seemingly unwinnable sixth place to accommodate the ambitions of John Short, who wielded greater clout than Singh by virtue of his position as state secretary of the Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union.

Similarly, Senator Eric Abetz and his conservative followers flexed their muscles by demoting to number five the only Tasmanian Liberal of ministerial rank, Richard Colbeck, after he distinguished himself as the only Tasmanian Liberal to support Malcolm Turnbull in his leadership bid last September.

Under the old system, voters discouraged at the thought of having to number every box below the line would simply have accepted the party ticket warts and all, and that would have been the end of that.

Relieved of that burden by the new requirement that a minimum of 12 boxes be numbered, voters instead registered their displeasure by going below the line in unprecedented numbers.

Singh now looks very likely to win a seat at Short’s expense, making her the first Senate candidate to win election outside the order of the party ticket since 1953.

The situation is somewhat less dramatic for the Liberals, but Richard Colbeck is at least in contention after scoring over half the Liberal below-the-line votes counted so far, which account for over a quarter of the total.

It would be nice to imagine that this portends a future in which voters thoughtfully exercise the power available to them to trump the factional deals that have done so much to bring the major parties into disrepute. However, the reality is that Tasmania is the only state where voters have the requisite familiarity with candidate-based voting, thanks to the operation of Hare-Clark at state level.

In Australia and elsewhere, hostility towards the political establishment ultimately runs deeper than boutique concerns about candidate selection, and only maverick anti-politicians in the Pauline Hanson mould seem capable of scratching the itch.

Memo to BillBowe from the 21stC – wakey, wakey!

“With the two major parties barely able to claim three-quarters of the vote between them, “… certainly NOT Lib/Lab. Or did you mean the Coalition (of 3 parties) & Labor? Still wrong, try barely two thirds.

“The blame for Hanson’s resurrection … ” lies with those damned voters – why can’t them wot nose best just abolish them and get new ones?

“the Greens, who combined with the government to pass ..” a decades long policy commitment of theirs – yeah, the sheer cheek of doing what was previously promised, when dey gunna get wit de prog. and “with a high-minded concern to curtail the power of party machines over voters’ preferences.” – how dare they!

When the Greens and the L/NP changed the Senate voting system and ended up with a much worse outcome, it seems that they deserve condemnation.

I don’t care how long the Greens had the ‘new policy’ on their books. Just goes to show how idealogically driven they are.

Never mind if the great idea works or not…just so long as they remain pure [and impotent]!!!

CML – why do you hate your descendants, if any?

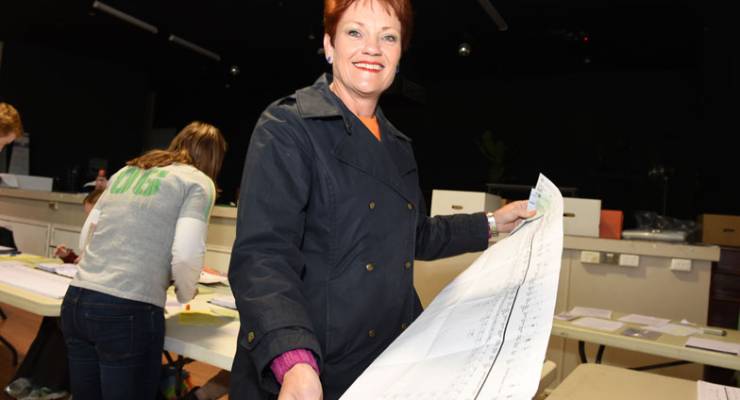

That pic of Hanson is a worry – since when has a candidate been allowed to handle a ballot durin the counting process?

“Mandate”? Isn’t that a cross between a unicorn and a phoenix?

Abolishing GTV makes preferencing transparent, returns integrity to Senate voting and returns the power of the vote to the people, where it belongs. You and I may not agree with many of them, but at least we will have the Senate the people have chosen, not one determined by multiple back-room deals with party officials and the likes of Glen Druery.