The Reserve Bank of Australia has let inflation slide.

Headline consumer price inflation has been below 2% since 2014, i.e. for seven consecutive quarters. That represents the longest period inflation has spent outside the 2 to 3% target band since the late 1990s.

The RBA’s preferred inflation measures — which normally stick even closer to the target band — are now both also below 2%, while headline inflation has just crashed to a fresh low of just 1%.

In that time the bank has moved its cash rate target three times, cutting it from 2.5% to 1.75%. Room to move remains. Why would it not do more to prevent this apparent failure?

Low inflation is a potentially huge problem. Deflation is famous for being a wet blanket on economic activity — if money might be worth more in future, why spend it now?

A paper presented by RBA economist at a 2015 conference suggests the RBA feels it is sitting pretty.

Written by the RBA’s Christian Gillitzer and John Simon, the paper comes with the standard caveats that the views in it belong to the authors. But its contents are extremely useful in interpreting the actions of the Australian government’s monetary policy arm.

It suggests the bank no longer worries about much about affecting inflationary expectations.

“Now that inflation credibility has been established, there is greater scope than in the early years of inflation targeting to tolerate meaningful deviations from target: consumers and firms are less likely to interpret deviations from target as revisions to the implicit inflation target than when inflation targeting was in its infancy.”

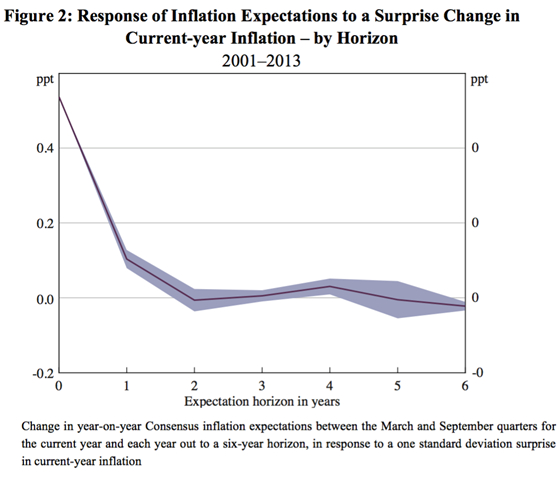

The data bear that view out. Shocks to inflation don’t change expectations much.

Source: Inflation Targeting: A Victim of Its Own Success? (Gillitzer, C, et al 2015)

It seems we either don’t notice the latest inflation data or don’t pay it much heed.

Even the most recent inflation expectations survey — despite coming during a record run of low inflation — reveals not a jot of concern from the Australian people.

In fact, inflationary expectations rose. The key measure from the Melbourne Institute Survey of Consumer Inflationary Expectations rose in July, to 3.7%. It had been 3.5% in June and 3.2% in May.

Does this suggest a survey sample full of deep calm and wisdom? Or utterly blithe ignorance? You decide.

But back to the RBA. Why would it even want the extra leeway afforded by stable expectations? That is, why not just attack low inflation whenever it arrives?

One answer, according to the paper, is to promote output growth. That makes sense when inflation is on the high side. In that scenario, cutting inflation means cutting output, according to the standard model. But now, inflation is low. The RBA could boost our lagging labour market and put inflation back into its target range. Why doesn’t it?

The answer seems to be house prices. It is obvious the RBA sweats on house prices. The RBA governor mentions them often in his speeches, and the trajectory of house prices is an important input to the financial stability goal that the RBA is duty-bound to pursue. A big house price crash would be, and cutting rates in a quixotic deflation fight would only pump up the housing market more.

This seems like a sound reason to let inflation get a bit low — preventing future financial system meltdown. But just because the RBA is happy doesn’t mean we shouldn’t ask the tough questions.

Inflation risk

Inflation targeting as a monetary policy tool has been around for only 25 years. It has been very good at locking down inflation in the countries that have used it. But inflation targeting was invented as a way of bringing down high inflation. It is not yet proven as a way of lifting low inflation, according to a paper by the Bank of Canada’s Michael Ehrmann.

And low inflation is a serious issue — it has taken root not just in Australia but across the developed world.

SOURCE: Targeting Inflation from Below: How Do Inflation Expectations Behave? Ehrmann, M 2015.

One possible solution to this tension is to change our inflation target. There is no guarantee the 2 to 3% range chosen by Australian policy makers so many years ago is relevant now. But such a move must be made carefully — and once only. A target that wanders will serve to loosen inflationary expectations far more than a few misses.

It is also worth mentioning a rising thread in macroeconomics that argues loose monetary policy doesn’t even lift inflation. Certainly, recent years have seen amazingly loose monetary policy globally and no consumer price inflation to speak of. That implies even if we cut rates it won’t solve our deflation problem.

RBA in flux

These difficult issues in global inflation and monetary policy making come as the RBA itself is in a period of change. Governor Glenn Stevens is leaving his post in September, and Philip Lowe will take over.

That change at the top could spur shifts in perspective and practice, especially coming just after the election of a new government eager to be seen making changes.

Good central banking has been a pillar of Australia’s success in the last decades. But that required flexibility — inflation targeting was adopted in 1993 by forward-looking RBA governor Bernie Fraser. If the changing dance of inflation, output and asset prices mean moving to a new monetary policy regime is once again the best solution, we should be willing to consider it.

Low interest rates have winners and losers. It might be worth considering what a decade of low interest rates might do to the losers.

“It is also worth mentioning a rising thread in macroeconomics that argues loose monetary policy doesn’t even lift inflation. Certainly, recent years have seen amazingly loose monetary policy globally and no consumer price inflation to speak of.”

Might that be because all that extra money is being captured by corporate interests and the 1% and not actually reaching the consumer. I am sure a bit of inflation could be created if helicopter money was applied to all consumers.

“The RBA could boost our lagging labour market and put inflation back into its target range. Why doesn’t it? The answer seems to be house prices.”

Perhaps. But equally, what about the next Big Global Shock? The RBA might just as well be holding back ammunition to deal with that (via China or Brexit or Italy or ….).

Lowering RBA interest rates has an effect on mortgage rates, not so much on credit card rates, where people might be tempted to spend.