Most media attention so far has been on the liveability of the athletes’ village, but inevitably it will turn to the Rio Games proper and, in particular, how each country fares in the medal count.

After allowing for various drug-related disqualifications over the succeeding four years, the official medal table for the 2012 London Olympics now shows the usual suspects: USA on top, followed by China, Great Britain and Russia. Australia ranked eighth and New Zealand 15th.

Why do some countries consistently win more medals than others? With the Games starting this weekend, it’s timely to revisit a piece I wrote at the time of the London Games, How can a country win more Olympic medals?

I noted then that those dissatisfied with their nation’s absolute medal count could always get solace from one of the many places offering alternative medal tables. For example, The Guardian’s Datablog shows New Zealand came fourth on the population-adjusted medals ladder for the London Olympics. That’s much better than its official 15th position and, perhaps equally important from a Kiwi perspective, it’s better than Australia did!

But whatever consolation population-adjusted rankings might offer, the number of citizens in a country is only indirectly related to winning Olympic medals. Sure, the third and first most populous nations on Earth took out the first two places in the official count in London, but the second most populous country — India — only ranked 55th.

In a model they constructed to predict the share of medals won by countries at the Beijing Olympics, academics David Forrest, Ismael Sanz and J.D. Tena found that when GDP was included, population size had a limited direct role in explaining the relative performance of countries. What seems to matter far more are factors like national wealth and a country’s preparedness to direct resources to fostering elite sport.

Their model was built on six variables (since they’re closely related, they call them co-variates). For each country, they measured:

- Gross domestic product;

- The number of medals won at the preceding Olympics;

- Government spending on sport and recreation;

- If the country is the Games host city or due to host the next Games; and

- If the country was a member of the former Soviet bloc or is a planned economy.

They calibrated the model using the medal results for 127 countries at each Olympic games from 1992 to 2004. They then forecast the total medals each would win at the Beijing Games and subsequently compared the prediction against the actual results after Beijing.

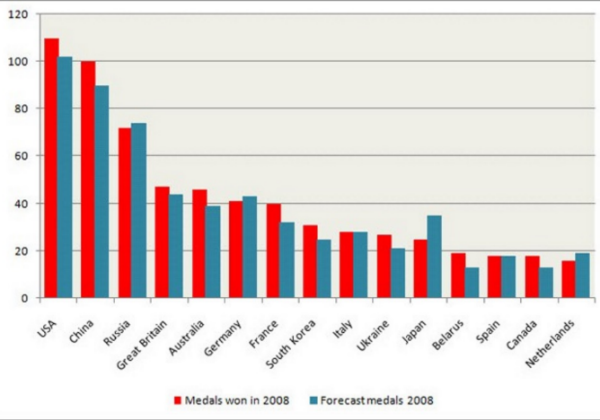

Medals won by top 15 winners at Beijing Olympics 2008 compared to prediction of model developed by Forrest et al

It’s evident from the exhibit above that the forecasts understated China’s, Australia’s and the US’ medal tally somewhat and overstated Japan’s. However, the authors say the R-squared between the forecast and actual medals was nevertheless an impressively strong 0.970.

Moreover, 99 countries were within two medals of the forecast. That’s not surprising given most were in a long tail, but the model was successful in predicting 13 of the countries that filled the 15 leading positions and in broad terms it got the rank order of those 15 right.

So the ability and preparedness of countries to channel resources into elite sport seems to be the key determinant of Games success. Great Britain is a classic example. It won only 28 medals at the Sydney Games and 30 at Athens, in both cases well behind the total haul (58 and 49) of much smaller Australia. However following London’s selection for the 2012 Games and a massive injection of funding, GB’s tally jumped sharply to 47 at Beijing, one more than Australia. The UK won 65 at London; Australia won 37.

According to Tyler Cowen and Kevin Grier, there are nevertheless other ways countries can increase their chances of winning more medals.

One strategy is to focus available funds on those sports which offer lots of medals. Team sports like hockey, soccer and basketball are expensive because many players have to be funded, but they typically only add a single medal to the scoreboard.

In contrast, sports like swimming, athletics, shooting, judo and cycling offer many medals and only require one or a handful of competitors per medal event. In some sports, a single competitor can enter multiple events and reasonably expect to do well. Michael Phelps, for example, swam in seven events in London (winning five medals) and Ryan Lochte swam in six (winning five medals).

Another strategy is to focus on sports in which the country has a comparative advantage. Cowen and Grier cite the fit between beach volleyball and the “outdoorsy” lifestyle of California, Brazil and Australia. Perhaps a better example is the fit between Australia’s high incomes and sports that are expensive for participants, like equestrian and sailing.

Kenya has a comparative advantage in distance running. Jamaica excels in sprinting, but rather than being the result of a “natural” endowment, it appears to be a specialisation it’s created. Cowen and Grier also suggest countries keen to increase their medal count can apply available funding to “importing” talent from other countries.

Steve Sailer argues rich countries seek to increase the number of women’s events because it’s the “easy way” to win more medals.

“If the Olympics still had the same distribution of events as in, say, 1952, poor countries would win a larger percentage of medals. Training women for some obscure macho sport is a luxury that only rich countries and dictatorships can do.”

There’s little doubt many advanced countries, including Australia, already implement some or all of these principles (I ignore illegal methods). They do it because success at the Olympics really matters to lots of people in lots of countries. It doesn’t matter for instrumental reasons, it matters because it makes those citizens feel good.

If the citizens of Australia knew the real cost of medals they might possibly think twice about the level of public funding provided for Olympic sport, but I very much doubt it. During the London Olympics, The Age’s Shaun Carney argued the Australian Institute of Sport was established to buy Olympic gold medals; he got it right, I think, when he said:

“There is not a shadow of a doubt that this had the support of a big majority of Australians. We like watching men and women in the Australian strip winning. It makes the rest of us feel like winners. In fact, the rest of us claim the victories as our own. ‘We’ won 16 gold medals in Sydney in 2000. ‘We’ took 17 gold at Athens in 2004.”

Personally, I wish Australians were as passionate and proud about our fellow citizens achievements in fields like managing the environment, social justice, establishing new businesses and technological innovation as we are about their sporting successes. Imagine if we saw addressing (say) inequality or fostering creativity as grand national projects on a par with international success in sport.

It’s tempting to think that as we become more confident as a nation of our place and status in the world, we’ll be less inclined to focus on sport. But I think that’s unlikely. Countries with longer histories than ours, like the US and Great Britain, show little sign of pulling back on Olympics expenditure. Indeed, at the time of the London Games, Australia’s Olympic officials argued a key reason why Australian athletes won fewer medals was because other nations had upped the expenditure ante.

* This article was originally published The Urbanist

As a person who is taking zero interest in the upcoming olympics, it’s obvious that if a country wins more medals than predicted then it’s cheating, and if it wins fewer then it’s underperforming.

Obviously Italy is the only honest country.

Yes, why don’t we celebrate people who have achieved something really important, in science or the arts for example?

And maybe the reason Japan didn’t do as well as predicted was because the age of the population wasn’t a variable.