Australian cyclist Anna Meares with her bronze medal

The Australian Olympic team arrived in Rio last month bearing the burden of chef de mission Kitty Chiller’s “ambitious but achievable” target of winning 45 medals — 16 of them gold — and a place in the top five on the medal table.

In the event, Australian athletes fell well short of Chiller’s target. They won 29 medals in total, eight of them gold, and ranked 10th. There’s no comfort from the many per capita medal tables either — Australia ranks even lower on them (and way behind New Zealand).

Naturally there’s much teeth-gnashing, hair-pulling and, inevitably, even a little finger-pointing. So why didn’t the Australian team improve on its London performance? Here are some of the reasons I’ve seen put forward:

- The team was weakened by external factors — Zika virus, leaky bathrooms — that miraculously didn’t affect athletes from other countries;

- Managers, coaches and trainers aren’t as good as they used to be and have slipped behind the competition in terms of both the physical and psychological preparation of athletes;

- The organisation of Australia’s Olympic effort isn’t up to par;

- The team’s medal chances were over-sold for marketing reasons;

- The most promising medal opportunities weren’t targeted; money was instead wasted on sports where Australia’s athletes have little chance of medalling;

- Other countries have become more ethnically diverse than Australia and are hence able to seriously compete for medals in a wider range of sports, e.g. track and field;

- More and more countries take Olympic success seriously and are spending up big on preparation of their athletes. Australia hasn’t increased its spending on athlete preparation in line with the increase in competitiveness of other countries;

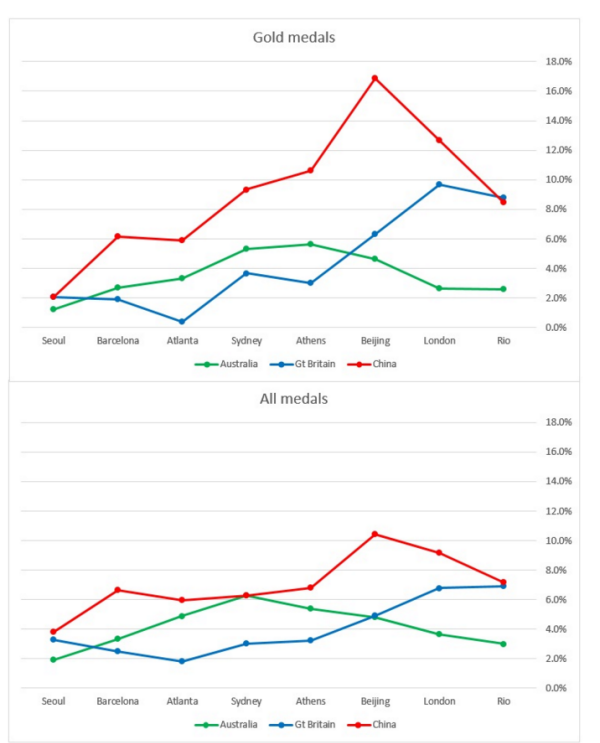

- The Sydney bubble lasted for 12 years (Atlanta, Sydney, Athens and Beijing), but now it’s gone. We’re back to where we should reasonably expect to be;

- Many athletes from other countries are doping whereas our athletes are squeaky clean.

Of these possibilities, the last three are the most plausible. Medal success at the national level is strongly associated with an external impetus like hosting the games, spending on athlete preparation, and state-sponsored doping (see Why do some countries win most of the Olympic medals?).

As more countries chase Olympic success, the $377 million spent by the Australian Sports Commission on elite athlete preparation over the last four years isn’t enough anymore.

The expectation of 16 gold medals was in any event ambitious. That’s the same number Australia won in Sydney when it hosted the Games. It’s close to the 17 golds Australia won in Athens when, like Great Britain this time around, there was a strong carry-over effect from Sydney 2000.

Having said that, while Rio was disappointing for the Australian team – its share of total medals fell to 3.0% from 3.6% in London – it wasn’t the disaster many make out. Australian athletes won eight gold medals, the same as they won in London. While the team slipped from eighth to tenth place on the medal table, both the eighth and ninth placed countries won fewer medals in total.

The stimulus from the Sydney games, which focused politicians, administrators and athletes on the chase for medals, has now faded completely. It seems Australia has reverted to its expected share of medals given its per capita GDP, strong anti-doping institutions, and a political culture that understands there are competing uses for funding.

Whether it matters or not is a separate question, but if Australians want to improve the medal prospects of “their” athletes in Tokyo and beyond — and I expect they do — then the most credible strategy is to increase funding for elite sport significantly.

Australian athletes will almost certainly win a larger share of the available medals at the Rio Paralympics. After finishing first in Sydney, the Australian Paralympics team ranked fifth in Athens, Beijing and London. That says something more positive about the country than ranking higher on the summer Olympics medal table.

*This article was originally published at Crikey blog The Urbanist

Australia doesn’t look too bad on the per capita tables, if we skim over very small countries that won very few medals. There are some standouts well ahead of us, such as NZ, Denmark and Hungary, but we sit about GB and miles ahead of the USA, China and Russia

No thank you. I’d prefer to have Australia on the bottom of the medal tally and have a country I can be proud of because of its social inclusion and culture.

Who do you think would pay for this increase in funding? We in regional New South Wales are still suffering because of the funding of the Sydney Olympics. It won’t come out of the pockets of the politicians or from those who matter to the politicians.

Why didn’t we win more medals? Simple. There were better competitors and they won.

Can’t the athletes, the managers and all the hangers-on just admit that Australian competitors just weren’t as good as others.

I really couldn’t care less bout the Olympics, the games are just a glorified sports carnival, with added ceremonies, corruption and hype. I think the real scandal is not the low medal tally, but the millions in state and federal funding that get pumped into this rubbish.

It’s a bit like the argument for funding art. Lots of people find nothing attractive in either, but it’s amongst the things that separate us from animals.

“As more countries chase Olympic success, the $377 million spent by the Australian Sports Commission on elite athlete preparation over the last four years isn’t enough anymore.”

Or alternatively, that’s a shiteload of money, especially considering the researched reports that state categorically that we would get far better value directing that at grass roots sporting organisations rather than elite athletes. I really couldn’t give a hoot if that meant that we got no medals at all.

“The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part; the essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well.”

Pierre de Coubertin

Sport used to be about taking part and teaching kids not only how to win but how to lose. Nowadays it’s become a corporate advertising festival that celebrates only elite athletes and suggests the rest just sit on the sofa and spectate.

Sport used to be fun.