The legislation for the marriage equality plebiscite will give an easy out to conservatives to seek to further delay marriage equality even if the plebiscite succeeds.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull introduced legislation into Parliament on Wednesday that would set up the plebiscite on marriage equality for February 11, 2017. Turnbull praised the legislation he once opposed as an innovative way of dealing with what he said people saw as a “moral issue”.

In its current form, it is likely dead on arrival in the Senate, with Opposition Leader Bill Shorten indicating that he would recommend to the Labor caucus in October to vote against it. Labor’s vote combined with the Greens, the Nick Xenophon Team, and Derryn Hinch will ensure the plebiscite’s defeat in the Senate.

If the legislation for the plebiscite succeeded in its current form, however, even a resounding “yes” vote would likely lead to the same debate that would be held in Parliament if a free vote were allowed today.

[How Coalition homophobes could set marriage plebiscite up to fail]

The plebiscite legislation makes no reference to the Marriage Act, the law that would have to be amended to allow marriage equality. But excluded from the plebiscite is any mention of whether people who identify as neither male or female would be permitted to marry. If the government aims to make the Marriage Act gender neutral after the plebiscite debate, it could replace references to “one man and one woman” with “two people”. But then conservatives could argue that was not explicitly covered in the plebiscite.

They could also attempt to say (although it is a much weaker argument) that by not specifying what law would be changed, the could enable the creation of a separate marriage act specifically for same-sex couples.

The plebiscite also makes no reference to religious freedom, although that will likely be one of the few arguments put forward by the No side. This will likely be something that will be debated as legislation is entered into Parliament, with lots of talk about Christian bakers and gay wedding cakes. If no exemption is made to allow bakers to discriminate against same-sex couples and the like, conservatives would have another way to ignore the outcome of the plebiscite.

At the very least, it means that any marriage equality bill entered into Parliament after the plebiscite — Turnbull has specifically not put a timeline on when that would happen — would be referred to a parliamentary committee for further consideration, and more delay before it would ever get to a vote.

Guardian Australia has reported that details on these concerns — withheld from the public — were given in briefing notes for the Coalition partyroom meeting, stating that changes to the Marriage Act would be proposed well in advance of the plebiscite, and Christian bakers and other so-called “conscientious objectors” would not be forced to provide services to gay weddings.

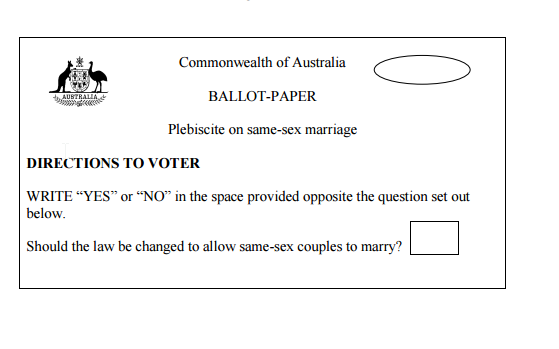

The proposed ballot paper for the plebiscite would look like the below:

This form is taken from the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act, which specifies that people must write either yes or no. It has been suggested that offering a “yes” and “no” box would disadvantage the second option.

Scrutineers will likely be closely examining every ballot paper after the plebiscite, as words associated with yes and no, such as “Y”, “agree”, or “Yaaaasss” as well as a tick would be considered a yes vote, while “N” or “never” could indicate no.

The vote will be compulsory, but informal votes will not attract a penalty — it’s a private vote anyway, so the government would have no way of knowing.

[Five ways to make the marriage equality plebiscite suck less]

On the donations front, tax-deductible donations of up to $1500 can be made to the specifically established Yes and No committees to then hand out to approved groups for approved advertising, which will include $7.5 million of taxpayers’ money for each side.

The Yes and no Committees will each be made up of two government members, two opposition members, one crossbench member and five members of the public, who will be able to apply to be considered for the panels. There will be no oversight over donations and ads during the plebiscite by third parties outside of this process.

There are specific obligations on the commercial broadcasters and SBS in the legislation to “give a reasonable opportunity” to both sides in the debate. This was something requested by the Australian Christian Lobby after Marriage Alliance had anti-gay ads rejected by SBS during the last Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. SBS, at least, can still charge for ads.

If there is any surplus funding in either committee at the end of the plebiscite, it is to be donated to DisabilityCare Australia.

To avoid another “Mediscare” campaign, the legislation makes it an offence to send texts or initiate robocalls about the plebiscite without including who authorised the message.

Outside of that, there is very little guidance in the legislation about what would happen if 50% +1 vote in favour of the plebiscite. The government would need to introduce another bill into Parliament to proceed the matter, in addition to the two bills in the House of Representatives, and two in the Senate that already seek to achieve what the government is determined to spend a minimum of $170 million justifying.

If the Coalition is unable to stand-up to their own lobby groups without putting on this costly charade, how deep does the rabbit hole go?

And we have George Christensen stating categorically that even if it’s a yes vote he will be voting the way his electorate votes so really, what is the point of continuing with this charade.

The plebiscite is rubbish as it does not bind the vote of MPs. It is just cowardice.

I can see a big problem with the question and the answer expected. Whether it’s a yes or a no that the voter will place in the box: a tick, a cross, a ‘Y’, a ‘N’, a yeah or nah … all these would be informal … best have the yes and no boxes already there for a tick or cross

The Rodent – who in a brisk morning’s legislation changed the Marriage Act, during his Reign of Misrule with control of both Chambers – must be so proud of his bumboy Abbott’s effort in foisting this abomination upon the public.

The continuing mystery is why Talcum submits to such daily humiliations.

Were he to discover some skerrick of self respect and defy the Neanderthals, bigots & troglodytes of the Party what are they going to do, really?

Another coup so soon, when the memory of the Abbottrocity still burns foully in the public mind?

I think not – self interest and preservation of privilege is a powerful sedative and psychic balm.