Tasmania’s federal Senate election went down to the wire. And when the dust settled, fewer than 150 ballots separated the Greens’ Nick McKim and One Nation’s Kate McCulloch.

McKim triumphed, at least in part because very near the final count, 1925 votes that had been going to the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers party exhausted. Under the old system, where parties or individuals assigned a preference to everyone on the ballot, it’s hard to see many Shooters’ voters having preferenced McKim over One Nation, or the Shooters’ party itself having favoured the Greens over One Nation when it came to preference allocation. It’s highly likely One Nation would have had another senator on the crossbenches.

The analysis comes from Monash University politics professor Nick Economou. “Clearly a very large number of far-right votes exhausted, and a Greens candidate succeeded,” he told Crikey. “It should concern us … With a margin so low, we have to wonder what would have happened if Shooters voters had been encouraged to cast more preferences.”

[Informal votes could have swung the election]

Exhausted ballots were always going to be an issue with the new Senate voting system. At this year’s election, more than 1 million ballots stopped being counted, or were “exhausted”, before the final Senate counts.

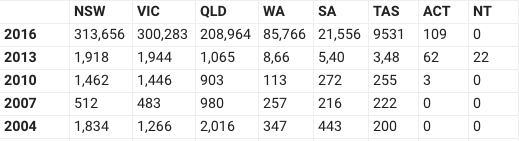

This is a dramatic rise on the last election, and every election previous. In recent elections — where voters either numbered “1” above the line and had the parties pick their preferences or numbered every single box below the line — the number of exhausted ballots never exceeded 7000 nationally. In 2013 and earlier, Senate ballots were exhausted only through numbering errors, rather than through voters intentionally choosing not to express full preferences — in most cases, parties expressed full preferences for them through the group voting tickets.

The new Senate voting system changed this by giving voters the option of numbering or expressing preferences for only a fraction of the total Senate candidates. In the 2016 election, this has led to a colossal increase in the number of exhausted ballots, from 6765 in 2013 to 1,040,865 — a figure 153 times higher. The fact that it was a double dissolution election may have exacerbated the figure.

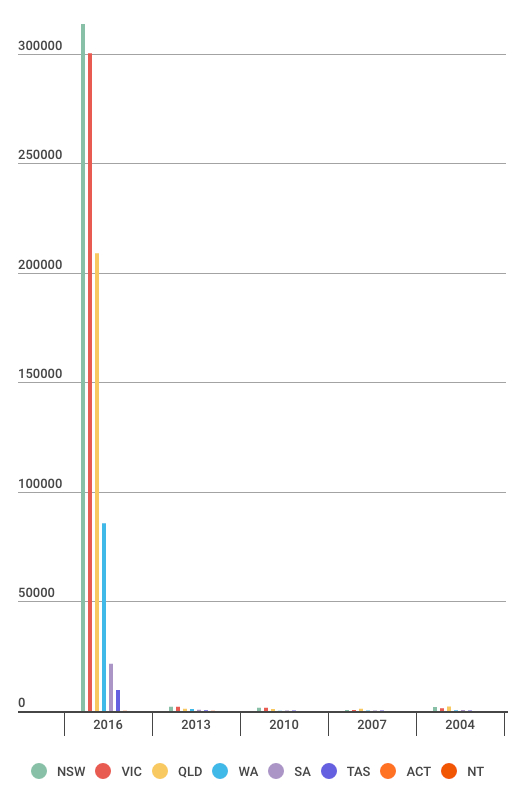

Above and below: The number of exhausted votes by state in the past five Senate elections

The number of exhausted votes is tracked by the Australian Electoral Commission at every stage of the Senate count. Almost half the exhausted votes nationally were in New South Wales, where 414,656 Senate ballots exhausted — just over 9% of formal (i.e. valid) votes. This is unusually high. Perhaps this was a function of the large number of candidates running, meaning people who numbered six (above the line) or 12 (below the line) preferences were leaving more boxes blank.

In Tasmania, there were 9531 exhausted votes — only 2.81% of all ballots. On the lower end of the scale, only 109 Senate votes in the Australian Capital Territory were exhausted. In the Northern Territory, not a single vote exhausted. In most cases, the high level of vote exhaustion had no impact on who was elected, but not always. Economou also points to Western Australia as somewhere where high levels of exhaustion in a close race advantaged some candidates (the National Party was excluded at the last count, and many of their votes exhausted — if they hadn’t, these votes would presumably have gone against the Greens’ Rachel Siewert).

[How your votes gets counted on election night]

Even a ballot that puts a major party candidate first or second can exhaust. Here’s how: say you’re a proud Tasmanian who really likes Eric Abetz and preference him first, below the line, on your Senate ballot paper. Now, let’s say Abetz is so popular with all the other proud Tasmanians that he actually exceeds his quota by 70%. That is to say, Abetz receives 1.7 times the number of first-preference votes he needs in order to get elected (not an unusual circumstance for someone high up on a major party ticket). What happens with that 70% surplus? Well, all the votes for Abetz get redistributed to their second preference, but not at the full value they were when they went to electing Abetz (the value is higher the higher the amount by which a candidate exceeded quota). This process continues for third-preference candidates — and fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, 28th and on and on right up until a voter stops numbering preferences. However, such high numbers of exhausted ballots at the 2016 election meant that the AEC could not continue with this process with many ballots past a certain number of candidates. The number of voters expressing preferences on the election or otherwise of candidates lower down the election order is thus smaller.

The issue for democracy, if there is one, is that if a ballot exhausts, it is necessarily less pivotal to the final Senate chamber than one which was still being considered at the final count. Some ballots are thus more powerful than others. On the other hand, exhausted ballots are the result of someone choosing to express no preference past a certain point. And this can be seen as a democratic choice as well.

Tasmanian psephologist Kevin Bonham says Economou’s analysis of the Tasmanian result is probably correct. Still, he’s not as fazed about it. For one thing, the level of exhausted ballots was significantly below predictions (departing Labor Senator Stephen Conroy was claiming before the election that 3 million ballots would be exhausted — the actual figure was a third of this). And exhausted ballots, Bonham says, are the “least of the evils”.

“I think that the exhaust rate was quite low. The problem is that there is no perfect solution. If you don’t have some exhaust, then the alternatives are group ticket voting and people send their preferences to places they don’t know about, or you force voters to fully preference and punish voters for mistakes, leading to informal ballots. There’s no perfect solution.”

“Exhausted ballots are less of an evil than group voting tickets, and less of an evil than high informal rates.”

I don’t see a problem here. The only objection I’ve ever heard expressed against preferential voting by everyday people is about having to assign a number to everyone, even parties they despise. Choosing to risk ballot paper exhaustion rather than helping to elect candidates they loathe seems like a reasonable democratic choice.

Exhausting your ballot pwns, voting for the senate was a real pleasure this time. I don’t even want to affect a runoff if it were only between candidates I didn’t want to vote for at all.

I’m not sure that the graph showing exhausted ballots in previous elections tells us anything of interest. Given that the old system did not allow for ballots to be exhausted I assume that the small number of exhausted votes arise from certain circumstances where informal votes were saved by savings provisions, or perhaps involve rounding losses when surpluses are calculated. Either way it tells us nothing much, a formal vote could not normally exhaust in the old system, it can in the new one. Comparisons of exhaustion level between the two are essentially meaningless.

Given that it is a vote for a multi-member electorate the effect of exhaustion is less than in a single member electorate (like the old QLD lower house), and given that previous implementations of full preferencing gave us either a large informal vote (as in the pre-1984 senate) or else gave power of preferencing to parties and preference whisperers (as it was before the recent changes), optional preferencing and the associated exhaustion of votes is a reasonable compromise. In almost every case the exhausted votes made up the unused quota at the end, there were very few candidates elected on anything too far short of a quota.

Also, I can’t see how a DD election would increase the number of exhausted votes, given the lower quota then I would expect it to give a lower figure if anything as voters allocating few preferences are more likely to have one of them for a candidate who is in the count for longer as there are 12 vacancies rather than 6. The higher number in NSW is most likely because the last few candidates remaining in the count tended to all be from the right (ON, CDP, LDP) and many voters may not have had a preference between them. The variation between states is probably largely a factor of the number of candidates (much fewer in Tasmania so fewer votes exhausted) and also related to whoever happened to be left late in the count, I wouldn’t try reading too much into it.

I certainly advocate that individual voters allocate as many preferences as possible to avoid their ballot exhausting since there is no way you can get a better outcome by letting your ballot exhaust if you do have any genuine preferences between remaining candidates, however on the whole exhausting preferences are not a big problem and those who were suggesting that it would be some sort of disaster were just wrong.

Stuart…if some senators were elected by ‘guesswork’, then we still have a problem. Doesn’t matter which state or how many ‘exhausted votes’ there were!

With all these so-called experts floating around the country, you would think someone could come up with a system which accurately represents the will of the people. What’s wrong with proportional representation???

I’m also one of those voters who likes knowing, that if my vote doesn’t count for the limited number of candidates I actually want in the Senate, then I’m happy to see it exhausted and NOT electing a loon.

All fair enough, and Stuart Johnson’s contribution is noted. This is my problem with the system, any system. If Abetz got 1.7 times the quota, what is the decision making process to work out where the .7 over the quota go to. Do we use my vote, which had Jacquie Lambie next, or Syd’s vote that had Peter numpty next? (Entirely fictitious, I would vote for a numpty over Abetz and Lambie every time)

It’s an arcane discussion, but goes to the heart of the issue of what is a valid vote, and what it’s worth. Is that .7 just handed over to Abetz parties second preference? Is it that simple? By what right is a political party allowed to use votes for other than the stated intention, in this case a vote for Abetz, even if he is over quota. Shouldn’t those votes exhaust first?

And this doesn’t even begin to look at the fact that a Tasmanian’s vote in the Senate is worth 16 times that of a New South Welshmen.

Perhaps it’s better not to look at how this sausage is made. It’s barely recognisable as democracy as the average punter understands it. As it stands now, virtually no-one can know where their individual vote ended up. I think that’s a big problem, but blind statisticians and political scientists are happy to gloss over it.

In the end, it doesn’t matter much, we end up with mostly numpties regardless. If it actually mattered, I’d be a bit pissed off. But I don’t see this exhaustion of votes being a big issue at all, and is more democratic not forcing my vote to go to someone who I don’t want to get it. Given the other problems with votes and values in the system as it was beforehand and still now, this is a pimple on an elephant.

“All fair enough, and Stuart Johnson’s contribution is noted. This is my problem with the system, any system. If Abetz got 1.7 times the quota, what is the decision making process to work out where the .7 over the quota go to. Do we use my vote, which had Jacquie Lambie next, or Syd’s vote that had Peter numpty next? (Entirely fictitious, I would vote for a numpty over Abetz and Lambie every time)” – Hey, I spent hours trying to get my head around this, so figured I could use some of what I learnt to answer your question. The answer is, both yours and Syd’s vote would count, each with a smaller value. When I wrote the votes are redistributed, I didn’t mean all to the same candidate – they’re redistributed to all the many preferences different people voted for, at a reduced value. So say they were redistributed at a 20% value (for this exercise), both Lambie and Peter Numpty would each be assigned 0.2 of a vote.

More broadly on your point, the system is so complex I actually simplified it as much as I could to write this piece. But my overall impression was, it’s complex to better capture people’s desires. If it was simple, it wouldn’t be as fair.