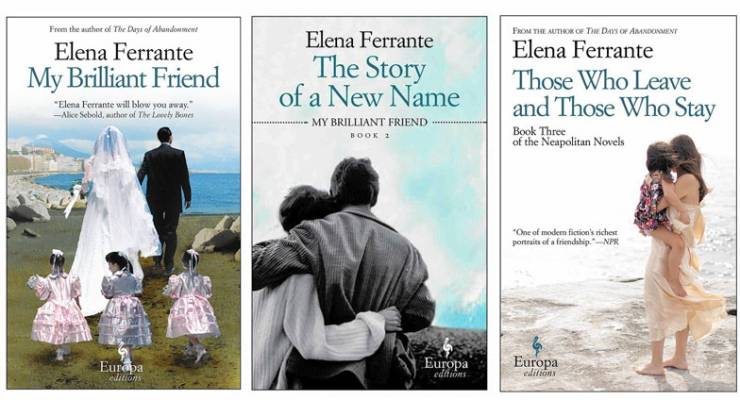

The woman who wrote the four best-selling “Neapolitan Novels” (My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name, Those Who Leave And Those Who Stay, and The Story of the Lost Child, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize) under the pseudonym Elena Ferrante has been outed by an Italian investigative journalist. But does the public deserve to know? And does that calculus change if Ferrante herself reveals a little about her life?

The revelation, carried in the New York Review of Books, has sent ripples through the publishing world. Many readers of Ferrante’s best-selling novels as well as other members of the literary community have responded by reiterating their desire not to know, particularly as Ferrante has said (in numerous interviews conducted via email) her anonymity was a protest against the personal branding required to sell books (for the purposes of this piece the name and identity of the author isn’t necessary, so Crikey will leave it unsaid — it’s not hard to find).

In the Columbia Journalism Review, Claudio Gatti, the journalist who unmasked Ferrante, says he did it because the author’s latest book — a non-fiction work with aspects of memoir to be released in November — contained what he knew to be false information about her. As he told the CJR:

“I’m accused of violating the privacy of Elena Ferrante? But the first person who violated the privacy of Elena Ferrante was Elena Ferrante! [She] wrote a book that is supposed to be autobiographical and was full of false information.”

In the yet-to-be-released memoir (Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey), Ferrante writes that she has three sisters and is the daughter of a seamstress from Naples. These facts are not true, Gatti says. He told the CJR:

“You cannot have your cake and eat it too. You are fueling the frenzy, the curiosity about her personal life, by the pieces of information that you are giving, and then you complain when somebody finds the real information. Explain to me how that works.”

According to local publisher Text Publishing’s blurb, Ferrante’s book, out November 1, is a collection of “letters to her publisher, interviews with editors and journalists, and responses to readers’ questions”. It is hard to argue that it didn’t seek to capitalise on the understandable public interest in Ferrante — her identity, Gatto says, was the first thing people asked him when discovering he was an investigative journalist from Italy. In publishing a non-fiction book with some personal (and allegedly incorrect) details, however, Ferrante appears to have unwittingly given Gatto the permission he needed to write about her life himself.

It’s a common dilemma for those with secrets to keep. In Australia, the affair between Cheryl Kernot and Gareth Evans (who were elected to Parliament as members of the Democrats and Labor party respectively) came out after Kernot wrote a book on her life in office in which she didn’t mention the affair. The book’s publication was a key justification for Laurie Oakes’ revelation of the affair, made in The Bulletin:

“While it is one thing for journalists to stay away from such a matter, however, it is quite another for Kernot herself to pretend it does not exist when she pens what purports to be the true story of her ill-fated change of party allegiance. An honest book would have included it. If Kernot felt the subject was too private to be broached, there should have been no book, because the secret was pivotal to what happened to her”

Rightly or wrongly, the justification shows what can happen when anyone who is hiding something offers readers a glimpse behind the curtain. Those with secrets to keep are hereby warned of the hazards of non-fiction.

Laurie Oakes is wrong. Kernov did not lie as did Ferrante. Oakes has a history of this kind of journalist gotcha. Remember him saying Gillard had opposed increasing pensions during an election campaign? His source – an unnamed member of cabinet. So we could not tell whether it was malicious or a lie