Opposition calls for ministerial resignations are fairly routine, but in the case of Attorney-General George Brandis, Labor’s demand for his head is entirely justified. Brandis has clearly, plainly misled Parliament, and on a very important issue. There’s no wriggle room or get-out clause for the provincial lawyer from Brisbane. He’s got to go.

The reason is the submission by the Solicitor-General Justin Gleeson SC to the Senate inquiry into Brandis’ direction of May this year preventing the Solicitor-General from providing any advice within government except with the approval of the Attorney-General. The central issue is Brandis’ statement to Parliament that he consulted with Gleeson in preparing the direction.

Gleeson’s submission is damning in the detail it provides about the lack of consultation by Brandis, his office or department. But it also shows an Attorney-General’s office engaged in a haphazard, indeed chaotic, policy process. As the second law officer of the Commonwealth, Gleeson is both independent and serves a crucial purpose within government. From his submission, it is clear that — entirely, it appears at the instigation of Brandis — his relationship with the Attorney-General, as the first law officer, has badly broken down.

On the central point about consultation, Gleeson provides copious detail and supporting documentation the discussion process about the drafting of a new Guidance Note — the document that provides the ground rules for how the Solicitor-General is used within government and what other agencies and departments should do in seeking his advice. Gleeson himself initiated this process near the end of last year after an unhappy time with Brandis and other ministers over some high-profile issues — and we’ll come to that. Brandis’ office was involved in those discussions — although apparently without enthusiasm — but at no time was there any consultation about a legal services direction of the kind Brandis ended up issuing, which is a quite separate matter and an entirely different document (for starters, it has the force of law, whereas the guidance note is just what it says, a guidance).

Brandis and his office have since tried to claim that the discussions about the guidance note were, more or less, the “consultation” about the direction. Gleeson makes it clear, page after page, paragraph after paragraph, that no direction was ever mentioned, nor was there any discussion of prohibiting the Solicitor-General from providing advice to other ministers (or the Governor-General), nor discussion of concerns about problems arising from such requests. The whole thing, Gleeson shows in forensic fashion, came out of the blue in May.

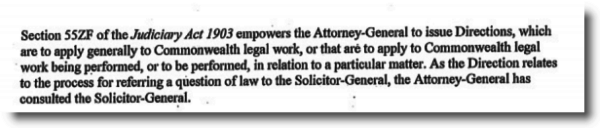

Problem is, Brandis told Parliament that he’d consulted with Gleeson on the direction. And not just in a throwaway remark in question time. Brandis said it in writing, in the explanatory statement accompanying the direction:

There can be no more blatant, or serious, form of misleading Parliament than to do it in a statement accompanying a legislative regulatory instrument. If the idea that you can’t mislead Parliament and get away with it means anything at all, Brandis has to go.

But Gleeson’s submission also illustrates serious problems in the performance of both Brandis’ own office and his department. Gleeson initiates discussion to overhaul the guidance note after thee particular problems. The first he mentions is the notorious citizenship bill, which the government eventually admitted in its original form was likely unconstitutional. That was down to cloddish Immigration Minister Peter Dutton and the Immigration Department, which has developed a reputation for non-transparency and incompetence under this government. From this, you could conceivably argue that Brandis was right to start demanding of his colleagues and their departments that they formalise — via him — better arrangements for seeking advice from the Solicitor-General — if he had the power to do so (Gleeson shows, conclusively, he doesn’t).

But the next two are from Brandis’ own department and Brandis himself. Gleeson complains that he has been bypassed in favour of the Australian Government Solicitor (the bureaucracy’s in-house legal service) on a matter relating to same-sex marriage (presumably the plebiscite, but Gleeson keeps the details redacted).

The third is when Brandis doesn’t bother asking Gleeson for advice on John Kerr’s correspondence with the Queen and proceeds to act in that matter blithely unaware that Gleeson had provided advice on that very issue to former governor-general Quentin Bryce two years before. It’s almost farcical that the government eagerly drops a story with Brandis’ brother in bloviation, Paul Kelly, in complete ignorance that the issue has already been dealt with by Gleeson previously. No wonder Brandis’ office snootily ignored Gleeson’s letter offering his advice.

The motivations behind Brandis’ refusal to use Gleeson are clear: he is naturally suspicious of independent legal advice (and, in the case of Gleeson, advice from a far better jurist than Brandis will ever be) and, worse, the Solicitor-General’s advice is considered as precedent by subsequent solicitors-general, meaning once the government has that advice, whether it likes it or not, it is stuck with it for good. That’s on top of the natural wariness of legal advice within the Public Service, where bureaucrats will resort to all sorts of measures to avoid receiving advice they — or their political masters — don’t want.

The problem is, Brandis lets this insularity and small-mindedness infect how he handles high-profile issues. And given Gleeson has, in effect, called Brandis a liar for his claims on consultation, it’s unlikely Brandis will be seeking much advice from the second law officer in the future if he remains Attorney-General.

Given this breakdown of relations, one of Gleeson or Brandis must go. And Gleeson hasn’t misled Parliament or let political calculation influence how he seeks advice on key issues.

I well remember watching the streaming video of Mr Gleeson appearing in the International Court of Justice when it was dealing with another one of Senator Brandis’s stuff-ups: the ASIO raid on East Timor’s lawyer. The case turned into a crushing defeat for Australia, though Senator Brandis later issued a bizarre statement the general effect of which was that he’d never enjoyed a s**t sandwich more in his life.

During the hearing, Mr Gleeson made a point of emphasising the extent to which the Attorney-General had been personally engaged with the issues. I thought at the time that the only way he could have made it clearer that the whole thing was Senator Brandis’s fault was by wearing an “I’m with stupid” T-Shirt.

Great reminder. Thanks Pedant.

There was also an interesting contretemps in the Senate Committee yesterday over whether the Secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department would be needed to give evidence, rather than just the Deputy Secretary who had been sent. The Secretary, of course, had been at the crucial meeting on which Senator Brandis relied to say that appropriate consultation had taken place.

And of course, the Solicitor-General himself has offered in his written submission to appear before the Committee if it so desires. It would be standing room only for that.

It takes a lying rat to spot a lying rat.

I was perplexed with this from the start. I was of the understanding that the Solicitor-General’s advice was to all government departments and authorities, plus the GG and the PM. How could it be, I thought, that the A-G could put himself between requests from the PM or the GG to the Solicitor-General. Being an appointment with a substantial degree of independence from politics, it seemed to be counter to so many principles of public sector accountability.

But I’m no lawyer, it just smelled fishy from the start. Brandis is on the LNP’s trophy mantle, another ‘worst-of’, this time in the form of the A-G.

Go after this plod.

With zero expectation bought ‘The Australian’ today “to inform” self on the AG v SG flameout. Not a single word or reference??

If Parliament fails to, or is prevented from addressing and resolving the falling out of the Nation’s two most senior legal officers and; accepts the AG position whereby the office of the SG is prevented from offering independent advice to government, it will indeed be an immense challenge to Parliamentary capacity to serve Australians. This is not a minor spat between two very senior servants of the people that may disappear (as clearly Murdoch Media desires) but a direct challenge to Parliamentary authority.