Mark my words, 2016 will be remembered as the year humans became obsessed with robots taking their jobs.

We’ve heard about the possibility of autonomous cars taking over from drivers, computer programs swiping the jobs of accountants and robots that write stories better than journalists.

[Can robots do journalists’ jobs better than we can?]

The apparent acceleration of progress in automation is leading to some cataclysmic thinking. Eminent physicist Stephen Hawking warned we could all end up unemployed.

Should we really be afraid? What motivates this fear? Is the pace of technological change really so much swifter now than in the industrial revolution?

We’ve lived through many periods of automation, long before the current conceptualisation of robot as software. It’s easy to overlook the number of roles that have been obliterated.

There is a cobbled laneway at the rear of my house, for example. Such laneways were once the workplace for people who worked carting away excretions. But the sewer pipe took the job of the nightsoil man.

Does anyone mourn that job? What about the cobble-hewers who were put out of work by the asphalt mongers and steamrollers of contemporary road making?

History shows us technological unemployment is fleeting. As the necessities of life are made absurdly cheap by efficient utilities, industrial agriculture and globalised textile industries, the economy shows no signs of ceasing to invent new things to want. Services — often labour intensive ones related to health, from surgery to counselling to yoga — are taking over the economy.

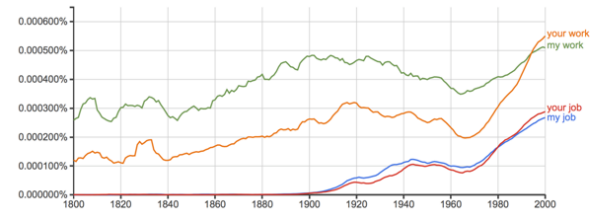

Examining the fear around “robots taking our jobs” reveals something interesting. The motivation could be less about robots qua robots, and more about our changing relationship to jobs themselves. The fear of something — anything — taking our jobs is fairly new, and growing sharply, as this graph from Google’s Ngram hints. (Ngram — a robot librarian, if you will — collects mentions of a phrase from books published between 1500 and 2008.)

For while robot technology is mutating rapidly, so is our relationship to work.

There have been two major shifts. First, from a concept of work to a concept of jobs. Then a second shift — to a growing concept of ownership of that job.

Jobs are, increasingly, the centre of our identities.

The issue is not merely cultural, it is also material. Losing your job is a huge source of fear, due to the rather dilapidated state of First World welfare systems.

The increased salience of “our jobs” could explain why economic nationalism is also having a resurgence in the West; Trump’s wall and Hanson’s senatorship being two examples that spring to mind. Foreigners taking your job is not so different to robots. The two fears are mirrors of each other.

(Perhaps worrying about robots taking your job is simply how employment-related fear job manifests in people with a bit more trade theory in their brains and a bit less racism in their hearts. Robots are, after all, a perfectly socially acceptable other to demonise!)

It is no surprise “our jobs” are a lightning-rod for passion. We vote for those who promise to protect them and increase their number. And we abhor those who put them under threat, whether they are robots or citizens of other passports.

Our fiercely protective relationship with our jobs probably reflects a lack of other sources of security in a frightening world. A great sign the world is growing more comfortable will be if — as during the post-WWII era — we notice a decreasing taste for the phrase “our jobs”.

We worry about our future jobs going to robots and we worry about not having enough workers to pay for the retirees. There is a fairly simple answer involving redistribution of income and shorter working hours. There are solutions, if implemented right, that can make the future continue the living standard growth we have had for the past decades but we need to maintain principles of equity and fairness.

During each shift to a new era – agricultural to industrial, industrial to services, new jobs have been created than destroyed.

However as we shift into the next era, technology is built into each startup, with startups requiring less workers.

Take for example the transport industry. This industry will undertake a major shit in the next decade as autonomous cars are introduced. Startups will be born that take advantage of driverless cars requiring no drivers. Where will the drivers shift too if new companies are created lean?

All industries will implement technology to reduce labor and head count – medical industry, teaching, construction, media.

It’s hard to see any future industry that is labor intensive due to technology filling labor needs.

Your example of the carter being replaced by a sewer is out of context as is the statement that technology unemployment is fleeting. In past shifts, new technology required jobs. In this new shift, technology does not need jobs.

As we shift into the next era, technology will be a job destroyer – not a job creator.

Maybe if we find more to want, other needs taken care of, there will be new things to be employed to do? …Or will our intelligent systems consume those jobs, as well?