The thousands of Liberal volunteers who manned polling booths in the last federal election have emerged as the unsung heroes of the Liberal Party, convincing more than one in four Liberal voters to follow the party’s preferred Senate preference order.

This is a much higher proportion than for any other party in this year’s election. While the double dissolution election threw up an odd grouping of independents for the government to negotiate with, the high proportion of Liberal voters who followed the party’s how-to-vote cards gave the party a greater-than-usual amount of control over what types of Senators from outside the fold got elected.

Giving parties the right to determine your Senate vote used to be simple — voters could just put ‘1’ above the line. The vast majority of voters did this — in recent elections, more than 95% of citizens voted “above the line”, giving whatever party they preferenced as their first and only choice the ability to distribute the rest of their preferences. But reforms to the Senate voting system, intended to give voters a greater say in how their preferences flowed to stamp out micro-parties being elected on very low primary votes, meant voters had to number at least six different party groupings, or 12 below the line. To follow a party’s preferred voting order, a voter had to pick up a HTV card showing the preferred Senate order, usually from a party volunteer manning the polling booth.

[Would the Senate reform spell the end of micro-parties?]

The Australian Electoral Commission has made the preferences of every single formal ballot paper available on its website. That means it’s possible, using open-source software we developed, to examine what percentage of voters who numbered ‘1’ for a party grouping then went on to number the rest of their ballot the way that party suggested on its HTV card.

In the 2016 election, most voters did not follow HTV cards. In fact, for every single party, a majority of voters did not. Only 2 million ballots, or 14.53% of all those cast, followed the preferences of the party they put first. This is a dramatic reversal on previous elections, where voters either had to give parties entire control over their preferences by voting ‘1’ above the line or were forced to number every single ballot below the line — a time-consuming and often confusing process. In 2013, 96.49% of voters decided to avoid the headache and just put ‘1’ above the line for their favourite party, giving parties with large numbers of voters great sway over the shape of the Senate.

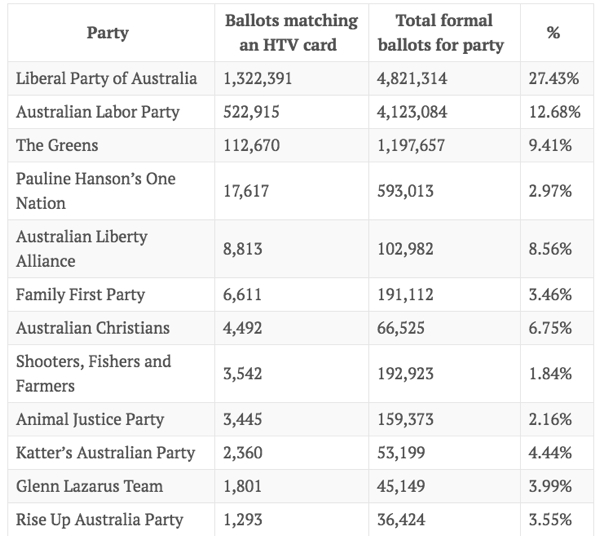

Those days are gone. While 93.51% of voters voted above the line this time, it doesn’t mean what it used to. Even above-the-line votes do not automatically give parties the ability to distribute your preferences — voters still have to number at least six party groupings to have a formal ballot. Following the Senate order a party prefers requires voters to pick up and follow that party’s HTV card, something 27.43% of those who voted for the Coalition as their first preference did. Labor voters were much more independent minded — 12.68% followed the ALP’s how-to-vote card. And just 9.41% of Greens voters followed the party’s directions. The figures for minor parties were uniformly lower again.

HTV usage by party. Full figures are available here.

On a state-by-state breakdown, voters in Victoria were most likely to follow their HTVs, with 19.76% doing so — a figure boosted by a mammoth 38.55% who followed the Liberal and National party HTV (the two parties ran on the same HTV card). The next most-compliant state was Western Australia, where 17.30% followed their HTV — the main beneficiary there was also the Coalition (31.03%), but the Labor Party (14.14%) and Australian Christians (12.28%) also had higher-than-usual HTV compliance.

[Poll Bludger: is Hanson’s return a symptom of a broken electoral system?]

It is conventional campaigning wisdom that the Labor Party’s “ground game” often trumps the Coalition’s, with Labor’s union links leaving it with a vast network of volunteers it can call upon in the lead-up to an election and on polling day to stand outside booths handing out HTVs. But the Liberals were more effective in getting voters to follow their HTV cards. This could be due to energised on-the-ground campaigners, or it could be something in the nature of Liberal voters themselves — perhaps they are more likely to trust their party’s decisions on preferencing. It is also possible that Liberal Party voters were voting tactically; they knew their party was likely to return to government, and so voters chose to support the Senate candidates the party would prefer in order to aid it to pass its policies through.

The 2016 election was the first time the voting system was tilted in favour of voters choosing their own Senate preference order. It isn’t yet clear if the figures are stable guides to how different types of voters behave, or merely the result of the dynamics of the 2016 election.

How to vote cards should be banned.

And we should get rid of above the line voting now that we are no longer required to put a number next to every no-name candidate….

Did the SA ALP think that I would follow their HTV card? After bring back Farrell? I may be simple but I know who I don’t trust.

I suspect it is something in the nature of Liberal voters. As the party is the party of screw the little guy for the large corporations, and as most people are the little guy, you have to be a bit simple to vote liberal in the first place, and then by definition will be happy to take any help in how to fill out a form with simple instructions.

Liberal voters are conservative voters, and they do what they’re told. Thinking not required.

Good comment, DB!

And look how well Talcum’s new rules ended up…biggest bunch of drongos ever in the Senate!!

At the last 2 elections I’ve worked on, 95% of the Liberal team were Asian students who were paid to work at the polling places. This is no doubt not true in Wangaratta or Bourke, but for coalition candidates in city electorates it seems that the old days of volunteers are over. Sad, eh, and heading in the direction that will ultimately give us representatives who bought their way into government.

The ALP in NSW had David Leyonhjelm in position 6. I asked the helpers how could that be & I was told the ALP had a deal that Leyonhjelm would do something for them in his preferences. I couldn’t bring myself to give him the slightest assistance & I suspect a lot of ALP voters felt the same. I think he ended up with 0.2 of a preference from the ALP. I sleep better knowing I wasn’t part of it.