Well, the shouting is over for a while — haha I’m joking, politics will be big shouting FOR THE REST OF YOUR LIFE! — but it’s died down a bit, to deal with the backlog. Chief among the things that need dealing with is “neoliberalism”, the question thereof. The term is everywhere; so, too, is the accusation, by liberals chiefly, that it has either no meaning, or means whatever you want it to. What’s the truth? Well, I would suggest that the term “neoliberalism” is 1) hideously overused, but when correctly used, 2) indispensable to understanding the current situation (and with the proviso that what follows is only one of several ways into it).

What do we talk about when we talk about neoliberalism? Many of those who object to it do so the assumption that it is being used to describe a mere idea or body of arguments — they wonder why “liberalism” will not serve equally as well. But neoliberalism doesn’t primarily describe a set of ideas, but a historical period — a set of interlocking events, institutions and conditions. Some of it has been driven by people with “classical” liberal beliefs, but it is far more than that.

By “neoliberalism” we mean the specific situation that emerged in the West, and then the wider world, in the period after the reign of post-war social democracy, from the 1940s to the 1970s. This period was characterised by the dominance of the “proprietary” state — i.e. a state that directly controlled significant sections of the economy and, in turn, shaped the character of social life. Education, apprenticeships, housing, public utilities, infrastructure, media — many people lived lives bound by non-market relations. This was paralleled by the persisting power of traditional institutions, such as churches, trade unions, voluntary associations, which resisted the market by their residual social power (the persistence of a ban on Sunday trading into the 1980s and 1990s is one small but telling example of this). How did this ban, inexplicable now, seem so obvious then? Because society embodied real limits to market relations, and that value was sufficiently established for such a ban to persist.

But that post-war ensemble disguised a dynamic process. Traditional authority was being worn away by modernity, and the desire for a wider personal freedom. By the 1970s, it was almost gone. Then social democracy started to fail too. Unable to move forward, to a socialist democracy, beset by the stagnation of the ’70s, its worst features — bureaucracy, inefficiency — came to the fore. Nationally bound capitalism was suffering from a profits crisis and sought both a lessening of boundaries (on the movement of capital) and access to socially owned institutions as a source of new markets and cut-price plant. The UK and the US, by the end of the 1970s, were in a position to convince a majority of voters that an extension of the market was the route to freedom.

This, then, was the (modest) beginning of the neoliberal era — one in which a decades-long suspicion of the extended market, born in depression and war — had been superseded by a tentative belief that it might offer a road to greater personal freedom and prosperity. Classical liberals presented this as “deregulation”, but it wasn’t; it was simply changed regulation, with the state benefiting capital rather than the general public. Thus, from the 1930s to the 1980s certain forms of union activity had been protected by law, while foreign transfer of capital had been heavily restricted. In the 1980s that was reversed; the closed shop and the secondary boycott were banned, global capital movements facilitated. A strong ideological push was then made to make such a re-regulation look natural, like the achievement of “freedom”. That is the neoliberal process par excellence.

For much of the 1980s, this was a limited transformation. But as the decade wore on, market power expanded, not merely economically, but culturally. Whatever limits traditional authority was able to impose started to be worn away, by a combination of the appetite for “transgression” — transferred from avant-garde culture to mass culture — and the atomising logic of the market. When you look back at some of the cultural controversies of the ’80s — the aforementioned Sunday trading, Madonna’s Papa Don’t Preach video, the Scorsese film Last Temptation of Christ — you are amazed at how mild was the offending text, and how much residual power traditional religious culture possessed.

Whatever limits were still in place at the end of the 1980s were swept away when the Cold War ended, and a global free trade and free-capital-transfer regime could be put in place. National regimes of “re-regulation” followed; the “end of welfare as we know it” under Clinton, full privatisation under John Major in the UK. In Australia, a wave of privatisations occurred under Labor. Social institutions that had been non-fee goods — medical, educational, utilities — became fee-based. Provision of them, when not actually privatised, was contracted out to private providers.

[Keane: neoliberalism is fine, but what we have is crony capitalism]

The wider cultural and social effect was not apparent at first, save to those looking for it; by the 2000s, it was becoming obvious. For decades, the power of capitalism to transform social relations had been held in check, either by socialist-oriented working-class forces, or, on the right, genuine conservatives. On both sides, it was understood that market relations, if allowed to take over too much of social life, are annihilatory and nihilistic. From the rise of the “axial religions” (Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity) onwards, the need to limit market sway had been paramount. Secular socialism had taken over that task for a century. The 1990s represented the first time in history that market logic was allowed to reach into every corner of social, cultural and institutional life, facilitated both by the state and by the cultural value of individualism, and the idea that every individual makes the meaning of their own life, from a market of images and signs available to them. “Neoliberalism” is the term we use to describe that state-market-culture ensemble, at a particular point in history. Don’t get hung up on the word — it’s just one term that stuck. Indeed, in the ’60s, “neoliberal” was used to described German-style social market politics. Didn’t stick, and in the ’80s, the word was repurposed.

Were this state-market-culture ensemble without problems, the term “neoliberal” wouldn’t exist. We use it as a form of diagnosis for a system that became autonomous, works, in part, against the deepest settings of human existence, and thus generates contradictions. Humans, as situated, encultured, bounded beings, gaining pleasure and meaning from the presence of known and loved others, abiding socio-cultural values, images and meanings, and a degree of fixed and inviolable “ground” to social life, don’t do well under a neoliberal order. As such an order wears away all social “ground”, millions seek to limit such ungrounding with simpler and more concrete “instant” values. This was the formula of the new right from the ’80s onwards. Settled social life would be winnowed by the effects of the market; state-supplied “traditional values” would surround such a process, like concrete round a nuclear reactor, and thus leave social meaning and meaningful life in place. Classical liberal theorists such as Hayek said this could be maintained if certain elements of social mystery — religion and the family chief among them — were maintained using state power.

[Rundle: Trump is the end of the left as we know it]

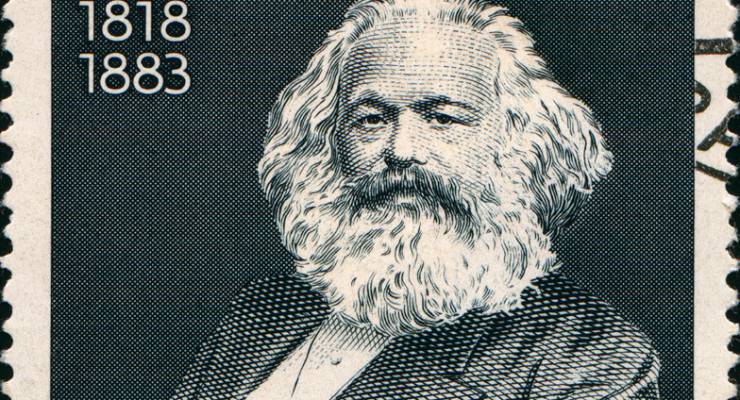

That isn’t what happened. Marx turned out to be a better guide to capitalism’s transformative power than Hayek. Everything people thought might be solid — their cities, their jobs, the boundaries of their culture, the social framework under which their children grow up — have been melted into air. Choice and dynamism have been amped, but even those who have benefited from that find their lives uncertain, dominated by debt, capable of catastrophic revision at a single moment. Much of the “growth” attributed to the era is erroneous. Essential costs such as housing have risen remorselessly, the expanded consumer economy has been fueled by open-ended private debt. The social revolution that took women out of the home and into the workforce has been co-opted, so it now takes two wages to gain the same life-security as could be achieved by one. And so on.

The neoliberal revolution left such social devastation, particularly in the US, that within a decade, millions were seeking out any simple formula of abiding meaning they could find. The rise of literalist religion was one example. Literalist religious-nationalism, such as the Tea Party, was another. The willingness of “centre”-right governments to use state power to extend the market in certain areas and restrict civic life in others — to give the appearance of social order — is neoliberal in the manner I’ve described. It will always default to regulate people as citizens first and capital last, if at all. In that respect, Mike Baird’s NSW government fits the bill exactly. Its lock-out laws — exempting a monolithic mega-casino, while penalising a mixed and complex social milieu like Kings Cross — use the state to reshape and repress social existence, in the interests of the smooth extension of capital’s reign. What would be anti-neoliberal — social liberal — would be to control and reshape the licensing within an area like Kings Cross and inner-Sydney to recognise the virtue of small venues, mixed neighbourhoods and multi-use streets as part of a living city.

[Rundle: the liberal centre that destroyed the world]

This is a global phenomenon. The transformation of the European Community into the open-borders, free-capital flow EU prompted the rise of nationalist movements in place of liberal social democratic dominance. Brexit and the rejection of Blairism was another. The rise of Trump and his nationalist message is another step along the way. Whether Marine Le Pen triumphs next year in France or not, the very possibility of such will indicate how egregiously the neoliberal era prompted the collapse of the liberal politics that were set within it.

Liberals confronted with this historical ensemble face a choice. They can either admit that their theory of human meaning and social existence is hopelessly one-dimensional, has predicted nothing, allows them to analyse nothing, and start to admit that the “neoliberal” sketch of existence describes a social reality that has to be addressed. Or they can become increasingly elitist, disdainful of the public, bleat on about the “nanny state” — i.e. the state controls, often demanded by the public, in the face of a culture reshaped by the market — and confine themselves to historical irrelevance. In this they will be following in the footsteps of their left complement, the Marxists (for Marxism is, in the last analysis, a form of radical social liberalism, sometimes supercharged with a bit of eschatological heft) who spent most of the ’70s trying to calculate the falling rate of profit to five decimal places, so they could keep the morning free on the day capitalism was going to collapse.

The Marxist collapse took 70 years. Liberals have had global control for less than 20, and they have been so rebelled against that little of their project remains. If they want a pluralist public sphere and a society where a robust notion of individual freedom survives, they will have to acknowledge that their politics left no place for desires and demands that people in their hundreds of millions are now making. If they’re not willing to do that, well, I hear the Henry George League has some office space it’s willing to rent out.

We now return you to your usual programming.

I agree Guy that neoliberal, like strategy and so many other words, has now lost all meaning. Sort of a form of doublespeak, however we got there in a completely different way than Orwell was predicting. Also resonant of Alice in Wonderland, this word will mean exactly what I want it to mean, nothing more and nothing less.

And here we are in Wonderland. For me, whether the definition is right or wrong, the essence of it is the obeisance to the market, the idea that there was a phantom invisible hand guiding it, and that anything that was visible had to be expunged (de-regulated, government out of the markets etc). This unfortunately misses the bleeding obvious that markets are neither fair, nor self-adjusting, in fact they are psychotic and psychopathic, the worst being the great god of the stock market that basically dictates public policy just through its irrational and meaningless gyrations.

And the ultimate horror of government’s selling off anything and everything, thus blinding the average nong from realising that some markets are better off without a government owner (Qantas, not because it’s better now, just better for the risk to be owned by private rather than public owners)

Mike Baird is the very heights of this, trying to sell of the Land Titles Office, seemingly unaware that they were providing a public good, and that making money was a corollary of that, and mistaking it for a revenue earner to be sold off. A dumber, and more ideologically driven mistake would be hard to come by.

At its peak though, neoliberalism is a religion, an ism, that defies breaking down by logic or rational discourse. A return to rational economics (evidence based – for the people who make up the economy, rather than capital) rather than ideological economic mythologies is the centre of the debates we will be having for some time to come, I suspect.

Great piece Guy. There is another side to this as well – by the end of the 70s and then the end of the Cold War, billions of people to our near north recognised a chance to sit down at the table and get their share of the wealth taken from them during a century of colonialism. They fell over themselves to encourage neoliberal states and MNCs to move whole industries out of the West to their countries, facilitated by flows of capital under the control of neoliberal untouchables like the IMF and WB. And of course it worked – pushed one end, pulled the other, a huge amount of wealth moved, with the rent seekers clipping the ticket on the way thru. The flow of wealth tho’ to a new elite had to be limited, the trickle down kept to a minimum – easy: just inflate and deflate a few cycles with unlimited debt followed by credit freezes. The result for the elites is acute concentration of wealth and control. The result among the dispossessed parallels that in the West, except that the fundamentalism is Islamic or Hindu, or support for totalitarian states.

Look, I think that’s a brave effort – much better than most – to get the term to mean something, but making it describe “a historical period — a set of interlocking events, institutions and conditions” rather than “a mere idea or body of arguments”. But I still don’t think it works. Compare it with (on your account) its predecessor, “the reign of post-war social democracy.” Now obviously there were a lot of other things going on at the time, but still you can describe social democracy as a coherent set of beliefs. You can point to actual social democrats and say roughly what they wanted and what values etc they held in common. Granted they didn’t have things all their own way in that era – that is, the features of the era were the product of more (I’d say much more) than the beliefs of social democrats – but the beliefs themselves can be identified in a more or less self-consistent sort of way.

Can you do that with “neoliberalism”? Who are the neoliberals? What do they believe? If you just mean “liberals” (or “classical liberals”), people who believe in the market as a means to human freedom, then you’ve got to somehow explain where all the anti-freedom stuff comes from. If you mean “rapacious business interests in alliance with old-fashioned authoritarians who’ve learnt some facile liberal rhetoric to use as a cover”, then I think the analogy with social democracy (or any other sort of ideological movement) fails; then you’re just talking about a historical era, not any real current of ideas.

Don’t get me wrong, I agree that there’s been a real current of liberal/pro-market ideas going over the last 40 years or so. I just think that to describe where we’ve ended up as being primarily the result of those ideas is unsupported by the evidence. Not just in the sense that the liberals haven’t had things all their own way (obviously the social democrats didn’t either), but in that most of the distinctive (and distinctively objectionable) features of our current situation are the work of people who are actively hostile to liberal ideas.

Sorry, should be “by making” in the second line, not “but making”.

Charles

Look, you’re trapped in circular reasoning. If the only thing you recognise is bodies of ideas, abstracted from any social ensemble, then of course you won’t acknowledge the argument that there are social-historical ensembles, periods that have a certain character that can be usefully encapsulated and described. What the ‘real’ status of that is, is another question – but it doesn’t have to be answered for the concept to be useful (anymore than the real status of an abstraction like ‘the nation’ or an entity like ‘the electron’ has to be decided). You’re proceeding from an anglo-analytical method, in which individual entities add up to a whole. Neoliberalism comes from a synthetic, wholistic approach, in which the whole and the part define each other. That’s why your explanation can’t do anything more than add up different forces – ie rapacious business people plus authoritarians – while an argument from a neoliberal diagnosis would say that the authoritarianism over persons is seen as a necessary and natural balance to the process of social atomisation caused by the extension of the market, and the corrosive effect on social solidarity. Eventually, this process starts to become an automatic one, subscribed to by both politicians and citizens. (possibly in the article i skated over that bit a bit quickly. Possibly needs a follow up).

My point is that classical liberalism, in the Hayek etc formulation argues that the catallactic order created by the market extends virtue and trust, so long as overarching constants such as religious belief. That obviously doesnt match what is happening – the free marketeers are the same people imposing the authoritarian state control of everyday behaviour.

At some point, if you don’t see society and historical periods as created out of an ensemble of embedded ideas, institutional theoretical production, and ideas-infused practices, then of course you won’t see the worth of such an argument. But that leaves you where you are at the end of your comment – insisting that the authoritarians and liberals are separate people, which is simply wrong, and self-serving for classical liberals who want to portray themselves as a valiant minority counter-tradition.

Effectively you have no way of explaining Mike Baird and his govt, and the character of NSW currently. Staying at the level of abstracted ideas means there can be no effective social explanation at all, simply moral and political criticism. Fine if one’s not interested in working out how things work. But some of us use theory to try and work out what’s going on, and what might happen next – and for that theoretical models of abstract ‘reals’ such as ‘neoliberalism’ are of use

best

GR

The

Thanks Guy – I don’t have a problem with using some neologism to describe a historical era by picking out a bunch of features, even if they don’t add up to a coherent ideology and hardly anyone actually believes in all of them simultaneously. (I still don’t like the specific</i? neologism "neoliberal", but that's no big deal.) My point was just that in that case it's misleading to draw an analogy with "social democracy", because I think that does add up (broadly speaking) to a coherent ideology.

But it seems you're making the further claim that even if the diverse positions (let's say market liberal + authoritarian) that make up "neoliberal" are at some level inconsistent, you think that level is abstract and unimportant and that in reality there really are (lots of) people who adhere to that set of positions. In which case that's an empirical claim, and I just don't think it's true. It seems to me that the serious free-marketeers and the authoritarians are usually quite different people. And I'd venture that that's what you'd expect, because the fact that the ideologies are inconsistent at an "abstract" level really does have a practical impact, because intelligent people have difficulty holding on to two broad incompatible worldviews at the same time.

I don't see why that means there can't be any "effective social explanation at all"; on the contrary, I think explanation of how the "classical liberals" have got themselves into a position where they're tools of the authoritarians cries out for a good social explanation, and I don't think it'll be very flattering to either group. But if you don't admit that there are two groups to start with then that's going to seriously impede the task.

BTW, loved the Vanstone piece today. Are you back in town?

Best,

CR

Aargh! Why can’t they have a comment preview function? Ignore all those italics.

charles

i think by serious free marketeers you mean the ones without power. lets look at those who combined the two:

Pinochet, supported by Hayek in 1973

Thatcher, enforcing Victorian values (section 28 and a host of other laws) in the 80s

Clinton, introducing the draconian criminal justice bill of the 90s, while marketising the US state and global society

Blair, introducing the ‘anti-social behaviour order’ etc etc

Cameron, extending police powers, criminalising social space, extending spy powers, internet surveillance, ‘family filters’ etc

etc etc

the point is that people want very little of the ungrounding that marketisation, privatisation creates. they feel their worlds being dissolved. if it is done without compensating statism, they resist immediately. so neoliberalism allows for the dissolution of grounded order, by handing the job of feeling secure over to the state (while also guaranteeing the right of capital to extend its power – ie by turning street protest from a misdemeanour into a felony, for example).

the more the social ground is undermined, the more people accept the state as a guarantor of safety.

You’re still talking about the circulation of ideas. But consistent free marketeers/libertarians are ignored. there is no libertarian society, because it doesnt work – people reject it immediately. and thus a neoliberal order becomes the only way by which capital’s power can be extended.

GR

OK, let’s accept for the sake of argument that a certain stage of economic liberalism is inevitably (or as a reasonable generalisation) followed or accompanied by an authoritarian reaction. (I don’t actually think this is true, but let’s not worry about that for now.) The question then is, is it reasonable or useful to tie the two togeteher under a single description like “neoliberalism”. I don’t think it is; I think it’s misleading.

When I say that the liberalism and the authoritarianism don’t fit together, I’m not (just) making an argument about abstract ideas, I’m making an observation about social reality: I don’t think you actually get people who embody these ideas as a single program. Of the examples you mention, Pinochet was just an authoritarian – sure he implemented some liberal economic policies to try to get his country up off the floor, but that doesn’t make him any sort of liberal. Clinton, Blair and Cameron it seems to me were just ordinary centrist politicians, picking bits and pieces of policy from different places as pragmatically suited them at the time. Thatcher is the one who really did combine at an ideological level strong liberal and authoritarian impulses – that’s what makes her such an interesting person, but also very untypical. (Mark Latham could count as another example.)

I understand the impulse to say that it was characteristic of a historical era to have pragmatic politicians combine market policies with social authoritarianism (it was), and therefore we should give that era or that process a name, and hey, why not neoliberalism? But I really think it should be resisted, especially if you’re going to use it in a comparison with a “social democratic” era, because social democracy was a real ideological-cum-social movement. It’s easy to point to dozens of actual social democrats, both in and out of politics, in a way that it’s all but impossible to identify real flesh and blood “neoliberals”.

None of this makes the liberals all pure and innocent, as you claim is my agenda. On the contrary, I think many of them made (and are still making) disgraceful compromises with authoritarianism. Hayek’s praise of Pinochet is one of the worst examples, but sadly not untypical. Even so, I don’t think that makes him an authoritarian: he was a real liberal, but one with human failings.

So, to sum up in a single sentence for your slower readers, the “neo-” part of neoliberalism means…? Guy?

One view has it that classical liberalism was all about extolling the virtues of the market while the neo version more stresses the failures of the state. It’s a view that’s pretty compelling, for mine: they may be 2 sides of the same coin but, given that your “proprietary” state’s explicit involvement in the economy was that much smaller pre-neo, it makes some sense that liberalism would develop in that fashion. But your view, Guy, is that the neo- part is just a re-orientation of the nature of state intervention – is that it?

A Slower Reader

I must say that the term “neoliberalism” confuses me a tad. It is often ascribed to the Tea Party who seem to be both socialist and free market at the same time. The same with the LNP, but particularly by the National Party.

I think that “plutocracy” has overtaken other social descriptions for what is really happening in that space. It is not even a movement at ground level, it is just a reflective surge in the direction prodded along by the political classes.

Hi D

as i say, dont get too hung up on the term. For a while in the 60s ‘neoliberalism’ was used for social market/ordoliberalism of the German type. That didnt take, and so it became available for this new formation, which came along after the Thatcher/Reagan decade – a relentless process of extending market relations to all areas of life (far beyond the original period of liberalism of the 1860s-1914) combined with an authoritarian use of the state to regulate persons rather than capital, as the marketisation process causes cultural and psychological chaos at the deepest human level.

It’s a ‘suspicion’ term – in other words it describes a process whose most fervent advocates wouldnt admit to. They’d say it’s “obvious” that the health system should be privately run on a market basis, and “obvious” that civic order – the order that allows for the smooth functioning of the market – should be preserved by restricting a citizen’s ability to get a drink after 11pm.

We who use the term use it as a diagnosis of a system in contradiction, that eventually delivers a grim society of scarcity and authoritarian rule – all in the name of ‘freedom’.

hi nf

the ‘neo’ is periodising. The high liberal period was from the 1860s to 1914 or just before – from the notion of free trade and human progress, undermined by the growth of imperialism and the nationalism that came with it, and then destroyed by WW1, followed by two decades of carnage and nationalist protection, then WW2, and an era of social democracy and social liberalism – whose collapse in the late 70s, ushered in Thatcher/Reagan, either a precursor or the first stage of ‘neo’liberalism. Yes, the ‘neo’ also includes the idea that the whole ensemble is contradictory at its root, it’s not merely a periodisation.

Papa Don’t Preach? Don’t you mean Like a Prayer?

oh gahhhhhh, yeah i do, and all the subs were too young to pick up the error (no offence, subs, that’s pure envy)

I was trying to recall exactly who was outraged about a girl telling her Dad she had got knocked up, but wasn’t going to have the pregnancy terminated. Even the Pope would have given that the thumbs up. Feel free to pass any future articles for me for proof-reading, at least in regard to late 20th C pop culture references.